Do the Debates Even Matter for Bloomberg?

It was Mike Bloomberg’s first time on the big stage, and it could hardly have gone worse. Until Wednesday night in Las Vegas, the Democratic debates had been civil affairs, with no candidate wanting to be the first to go hard negative and be seen by voters as fragmenting the party. But the same courtesy apparently did not extend to a late-to-the-party mega-billionaire whose record-breaking campaign spending has been criticized as an attempt to buy the Democratic nomination.

Bloomberg was savaged all night, on all fronts: on his stewardship as mayor of New York’s controversial stop-and-frisk policy, on the non-disclosure agreements signed by women who made accusations of sexual harassment and gender discrimination at his companies, and on the presumptuousness of his make-it-rain campaign strategy. The attacks landed more often than they didn’t, and it’s easy to imagine many viewers coming away from that debate with a substantially deflated opinion of Bloomberg. But here’s the $400 million question: Will it matter? The answer: Maybe less than you’d think.

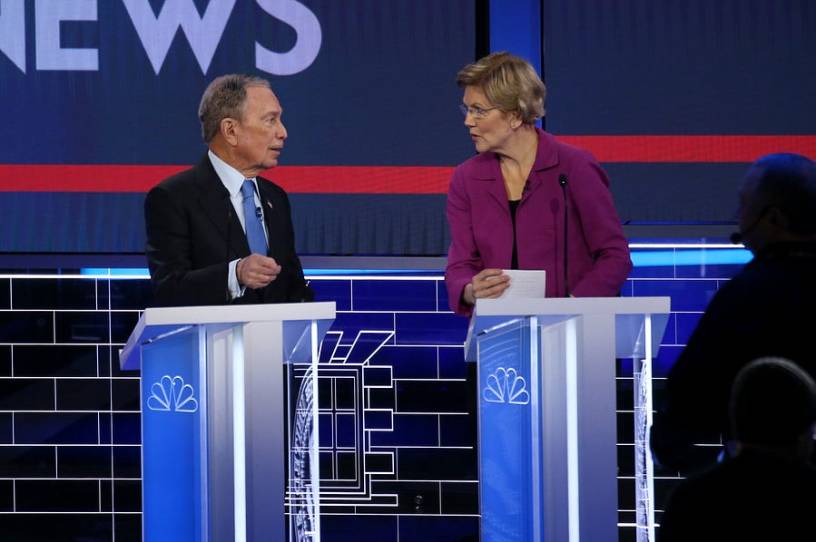

The most brutal blow of the night came at the hands of Elizabeth Warren over how women have been treated at Bloomberg’s companies. Early in the debate, Bloomberg had tried to head off allegations of workplace sexism that have cropped up against him in recent days, insisting he supported the #MeToo movement and that he had many satisfied female employees at his business.

Warren seized the opportunity at once: “I hope you heard what his defense was: ‘I’ve been nice to some women.’ That just doesn’t cut it.” The senator then repeatedly urged Bloomberg to release the women who had accused him of misconduct from their non-disclosure agreements.

Looking grumpy and harried, Bloomberg demurred: “We have a very few non-disclosure agreements. None of them accuse me of doing anything other than maybe they didn’t like a joke I told. … They signed those agreements and will live with it.” The response prompted jeers from the crowd.

In an ordinary presidential primary, a single bad debate performance can be enough to sink a candidate. Think of Rick Perry’s failure to remember the name of a federal agency he would abolish, or Chris Christie savaging Marco Rubio for his robotic recitation of talking points before the New Hampshire primary in 2016. Taken purely on the merits, Bloomberg’s performance certainly ranked among those: He looked consistently lemony and defensive, out-of-touch and mean, a far cry from the jovial, confident Trump-terminator he’s portrayed himself as in campaign branding.

But this Democratic primary isn’t an ordinary primary, and Bloomberg’s electoral strategy has never hinged on scoring an effervescent victory on the debate stage. In fact, there’s a sense in which the whole thesis of the Bloomberg campaign is that, in a divided field that overwhelms voters with options, a big enough infusion of cash can short-circuit the system and render sorting mechanisms like debates irrelevant altogether.

Consider the circumstances under which Bloomberg got into the 2020 race. From the beginning of the primary, Democrats were determined not to repeat the same mistakes they made in 2016 by appearing to prejudge the race in favor of or to exclude any particular candidate. As such, they bent over backward to keep things inclusive throughout 2019. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the debates, where month after month the DNC fielded crowded stages of candidates, slowly tightening the qualification thresholds and doing little to eliminate candidates with only the barest whisper of support.

This strategy ensured that Democratic voters wouldn’t have choices taken away from them by the party brass. But it also helped to create the circumstances Democrats found them in late last fall: Still heavily divided, with no commanding frontrunner, and with voters feeling less spoiled by their choices than paralyzed by them. Despite the sound and fury of a year of campaigning and dozens of hours of debates, a remarkable number of voters remained undecided about who they would support. And they were increasingly tuning out from the events designed to help them pick: the 18 million who tuned into the first Democratic debate last June had dwindled to a third of that by November.

Enter the Bloomberg rope-a-dope: Skip all that mess, then swoop in and scoop up voters who were tuning out by giving them a vision of an entirely different, much simpler primary. Positively saturate them with ads making a simple case: Donald Trump is a wretched president, and Mike Bloomberg can beat him. Ignore the fact that other candidates are making the same argument. Ignore the other candidates altogether. Trust only in the fact that you can buy more ads more often and in far more places than anybody else, and hope that voters will default to you rather than face the daunting task of trying to pick a candidate on the merits.

So far, it’s an unproven strategy. But it’s hard to see how one bad debate performance sets it back much. After all, the voters Bloomberg is targeting are the ones least likely to have seen that performance at all.

When we get to the far side of Super Tuesday, we’ll have a better idea of whether Bloomberg’s gambit has paid any dividends. In the meantime, however, rumors of his campaign’s death are greatly exaggerated.

Photograph of the Las Vegas debate by Mario Tama/Getty Images.