Though I know it’s coincidental, I imagine Eric Dezenhall’s publisher is delighted that his tightly plotted revenge thriller, False Light, is being published so soon after the “resignation” of another journalist from the New York Times. (Though, to be honest, it doesn’t exactly take a miracle to time a novel’s release around the departure of a high-profile reporter or editor from a mainstream outlet, since they happen with such metronomic regularity these days). False Light is tonic for anyone concerned about clickbait sensationalism and increasing illiberalism in newsrooms.

False Light’s protagonist, Sanford “Fuse” Petty, is not built to flourish in the modern journalistic ecosystem. He’s a fiftysomething investigative reporter, technophobic and old school. Though he’s decidedly left-leaning, he’s not about to stop chasing a lead just because the villain turns out to be on “his side.” One such story has gotten him crosswise with his employer, the Capital Incursion, and as the novel opens, he has begun a leave of absence from his job, pending a disciplinary investigation.

Just as Fuse is trying to figure out what to do with his unexpected windfall of time, he’s approached by his oldest friend, Kurt Rossiter. Kurt wants Fuse’s advice about a situation with his daughter, Samantha, who says she was sexually assaulted by her boss, the prominent journalist, Pacho Craig.

Assault victims usually have to choose between reporting an incident or remaining silent, but after laying out the options, and candidly describing the downsides of going public—the inevitable attacks on Samantha’s reputation, and the iffy chances of successful prosecution—Fuse offers a third option: revenge.

While the inciting incident in False Light is a #MeToo story, and the issue is explored (with care, but in all its messy reality), the novel is not about #MeToo. The bulk of the narrative, rather, is devoted to Fuse’s attempt at retributive justice.

Vengeance is definitely for Samantha, but it doesn’t hurt that Pacho Craig is the anti-Fuse. Craig has just the right stuff to thrive in modern media. His weekly “gotcha” ambush interview segments for MyStream, a virtual news network of citizen journalists, had made him “the Digital Age’s dashing Prince of Confrontation.” He’s reckless and a hack. Unlike Fuse, however, he never chooses the “wrong” target.

Fuse devises a scheme—elaborate, occasionally antic, and definitely on the shady side of the law—and enlists the help of some likable-if-sketchy characters he’s cultivated as sources over the years. They include Eddie Fontaine, a drug kingpin who is tired of the game, but has turned out to be a dab hand at investments and is working his way toward retirement; and “Goblin,” a consultant to the NSA, whose real name Fuse has never known. While he’s got them on the job on behalf of Samantha, Fuse also has them do a little digging into the circumstances behind his suspension from Capital Incursion.

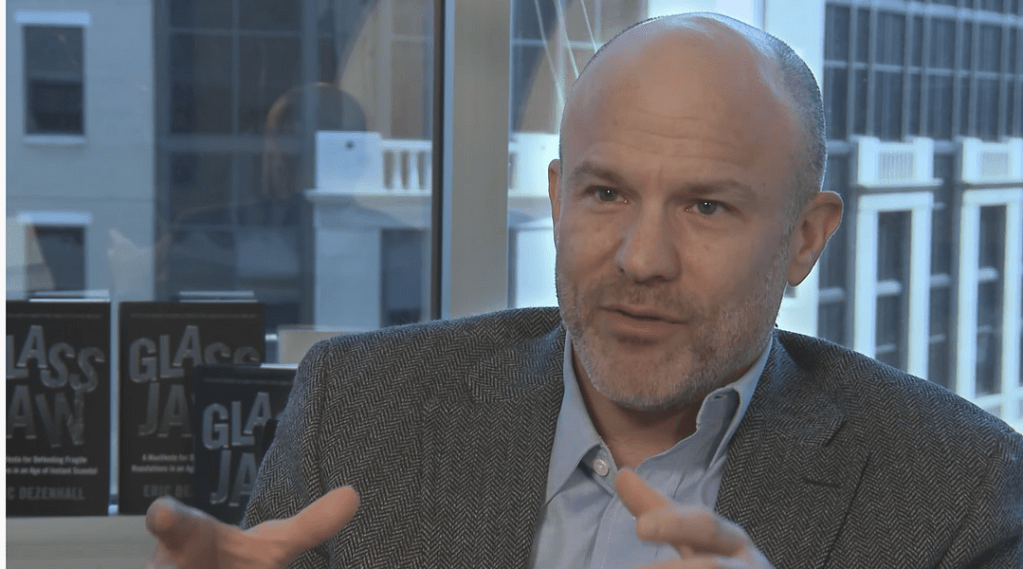

Novels of this sort are often eye-rollingly outlandish, but Dezenhall, a crisis communications expert, has had 40 years’ experience helping clients manage damaging reputational attacks. Dezenhall is so intimately familiar with how smear campaigns are orchestrated, I can only imagine how much fun it was to write about being on the other side of the table, as Fuse hatches his plot to bring down Pacho Craig.

False Light is a propulsive story, with plenty of wit and crackling dialogue, but Dezenhall also delivers a fully realized character in Fuse, revealed through interactions with friends, his wife and daughter, and especially his father.

Fuse’s father has an almost magical ability to elicit sympathy from people with his woe-is-me tales, but Fuse knows the real Nat Petty. As the reader learns more (including how Fuse got his nickname), it becomes clear that while he might feel like an endangered species, Fuse did pick up one important jungle skill in his childhood: the ability to spot a predator in disguise. This power enables him not only to see through his father, but also through manipulative character assassins masked as journalists.

The question of whether this power is sufficient for Fuse to succeed in his mission, or to clear his name at work, keeps the pages turning. What makes the novel so satisfying is the knowledge that, even if he doesn’t, at least he’s fighting back.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.