Are Rising Crime Rates a Blip or a Longer-Term Concern?

Americans will remember 2020 for lockdowns, protests, and a controversial election—but they might also remember it for a historic surge in murders.

The FBI won’t release its official data until September, but preliminary findings from the bureau and local law enforcement agencies indicate that murder rates rose by at least 25 percent nationally. If that bears out, the U.S. would eclipse 20,000 murders in a year for the first time since 1995.

“We’re going to see the largest one-year rise in murder that we’ve ever seen,” Jeff Asher, crime analyst and co-founder of AH Datalytics, told The Dispatch.

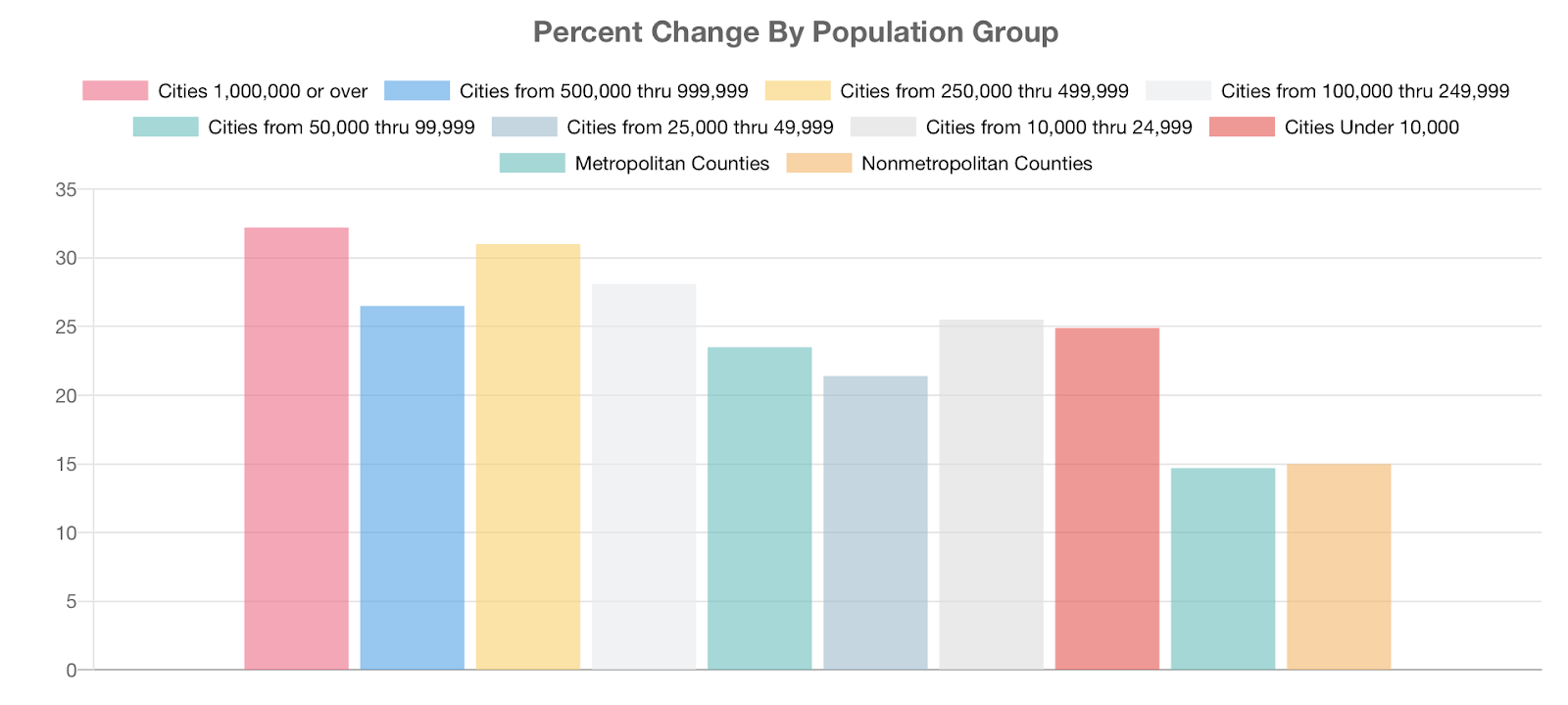

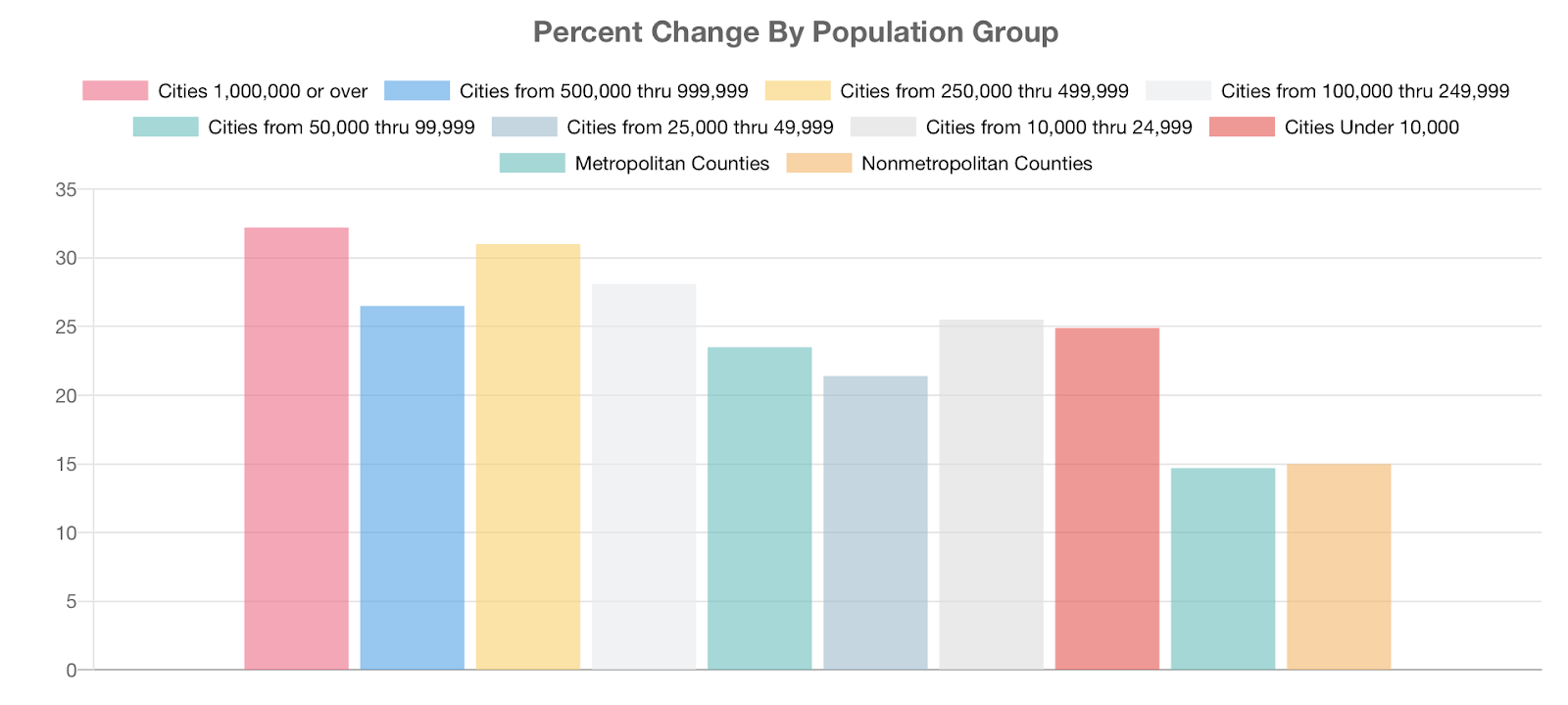

The rise in murder was not limited to large cities, and it’s not just a blip. The deadly wave of violence has carried over to 2021 as the number of homicides rose about 20 percent compared to the first few months of 2020 and by about 49 percent compared to the same time period in 2019.

Research indicates that cities that increased their police budget were just as likely to see an increase in murder as places that decreased them—the murder rate was up in 84 percent of cities that reduced their budget and 74 percent that raised them.

However, Asher says we shouldn’t be surprised since “most budgetary changes were relatively minor and happened later in the year.”

While experts have cited the stress of the pandemic as one source of the uptick in murder, it’s not the only explanation. It’s worth noting that murder rates have been slowly increasing since hitting a modern-day low in 2014.

And the pandemic can’t explain away other statistics. The annual rate of aggravated assault increased by about 10 percent in 2020—after increasing by only 1 percent in 2019. Interestingly, assaults were on the rise in January and February even before COVID lockdown and the summer’s protests. The rates remained above average for the rest of the year but peaked between the summer months of June and August.

Unlike aggravated assault rates, motor vehicle thefts seemed to peak in the early months of the pandemic—leading to an increased rate of at least 10 percent by the end of the year. Arson also increased about 23 percent nationally and 56 percent in cities with more than 1 million people.

Murder, aggravated assault, and motor vehicle theft rates remain on an upward trajectory. A sample of 32 cities with data from the first three months of 2021 show aggravated assault rates are about 7 percent higher than they were in 2020, and motor vehicle thefts have increased about 28 percent during the same time period.

What crime is falling?

Despite historic surges in homicide and aggravated assault, overall violent crime increased by only 3 percent—a significant increase but an uncommonly large difference between the violent crime and murder rate.

“Usually, violent crime and murder go in the same direction at the same rate. It’s very unusual to have this large of a difference between the change in murder and the change in violent crime,” Asher told The Dispatch.

Steep declines in rape and robbery drove down the violent crime rate—each decreasing by double digits.

Property crime has been decreasing for generations but saw a steep decline in 2020 because of COVID lockdowns. Burglary and larceny-theft were way down, resulting in property crime decreasing by about 8 percent.

Property crime makes up a significant majority of overall crime each year—it was about 85 percent of overall crime in 2019. So, despite a historic surge in murder and a substantial increase in violent crime, overall crime likely fell in 2020.

“A way to look at this is that the crimes that rely on mobility fell and the crimes that generally occur between people that know each other rose,” Asher said. “Also remember, crime is badly underreported. It depends on the crime, but we have all sorts of evidence that this is the case.”

How do our crime rates compare to the early to mid-1990s?

Both property and violent crimes effectively peaked during the early 1990s. Since then, both property and violent crime have declined by over 50 percent. Even after the increase in violent crime in 2020, rates remain less than half of what they used to be.

There is no consensus among experts on why or how overall crime has declined so much since the mid-’90s. On a recent episode of the Remnant, Shawn Bushway, a scholar at the University of Albany and the RAND Corporation, acknowledged the difficulty in explaining crime trends.

“It’s about the social phenomenon that happened in time, then those things change. But crime trends are hard. Every crime trend is explained and motivated by a different set of factors. It’s not a predictable trend,” he said.

John Roman, a senior fellow at NORC at the University of Chicago, believes that the pandemic taking young men out of their daily routines can, in part, be used to explain the rise in homicides.

“The pandemic took a lot of young men out of their routines and put them in neighborhoods with a history of violence and trauma. Anytime you have dense clusters of young men with little to do, you have a recipe for violence,” Roman told The Dispatch. “You also had a tremendous decrease in local and state government services. When the pandemic hit, there was no source of social services like there was before—schools were closed, community centers were closed, and churches were closed.”

When asked if he thinks 2020’s violent surge was an aberration or the beginning of a dangerous trend, Roman expressed concern.

“The problem is that the trauma is cumulative. When there’s been a shooting in your neighborhood, that trauma doesn’t just disappear—there’s usually retaliation. That cycle of retaliation is going to continue for a while.”