In a sense, it’s pointless to debate whether the United States should have a more hawkish policy toward China, because we’ll have one regardless of how the 2020 elections go. There’s a broad consensus among both of the political parties and foreign policy experts across the ideological spectrum that the U.S. will need to be more confrontational and assertive with China in the years ahead.

But the more decisive factor is that Americans have been souring on China for years, and the pandemic has only hardened feelings. Last month, the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of Americans have an unfavorable view of China. A Harris poll found that 90 percent of Republicans and 67 percent of Democrats think China was at least partially to blame the spread of COVID-19. A new Politico/Morning Consult poll found that 31 percent of Americans flat out consider China an “enemy.”

In short, the leaders will be following the voters. That’s why the “debate” — really just a two-way barrage of insults — between the Donald Trump and Joe Biden campaigns boils down to who can be trusted to be tougher on China.

Count me among the hawks. The Chinese Communist Party may not have any ideological connection to actual communism anymore, but it retains the brutality, bigotry, and authoritarianism that gave communism its bad name in the first place.

But “hawkishness” or “toughness” or whatever word you prefer isn’t an actual foreign policy. Hawkishness is a means, not an ends.

So what are those ends? What do we want to achieve? And what calamities do we want to avoid?

The answers to the latter are easiest. Only fools want an actual war with China. Even if it didn’t escalate to a nuclear exchange, a major military confrontation would offer few benefits for the U.S. Personally, I’d be in favor of regime change in China if that were achievable with relatively low costs in blood and treasure. But I’ve seen no plausible plan for that.

We also do not want to create an international financial crisis or destroy America’s status as the world’s reserve currency. So that means defaulting on our massive debt to China is out. Bringing all of our industry home sounds attractive, but if you ask any informed person about that, it’s easier said than done. Under the best of circumstances it would take us years to dismantle the supply chains that currently exist without needlessly damaging our economy.

Pick whatever goals you like; a smart foreign policy would try to bring the rest of the world with us at the end of that process. If you think of countries as customers for our products and services, we do not benefit if we break off from China and no one comes with us.

Polls across Europe show growing hostility toward China, but they show a dismaying distrust of the U.S. as well. Thirty-six percent of Germans say the pandemic has caused them to think less of China. But the same poll found that 76 percent of Germans felt that way about the U.S.

Of course, countries aren’t just markets for our wares. They’re also current or potential allies or enemies, and a policy that creates more allies for China and fewer for America would be foolish.

Consider Trump’s intensifying attacks on the World Health Organization and his threat to withdraw all U.S. funding from it (which he can’t actually do without approval from Congress). Trump is right about many of his complaints, even if he gets some of the particulars wrong. The WHO was too deferential to China in the early days of the pandemic. But what would be the net result of American withdrawal? China would be left standing as an even bigger influence on the organization.

It’s analogous to Trump’s misguided decision to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. That was an effort to counter China’s trade advantages in the region. Trump’s unilateral withdrawal was “hawkish,” but it was the kind of hawkishness China welcomes.

Perhaps the goal with the WHO is simply to remind it of its responsibilities, in which case a little bluster is fine. But if we’re entering into a great-power rivalry with China, the goal has to be to line up the most desirable players on the board with us, not them.

That shouldn’t be hard, but I see no reason why we should make it harder just to sound tough.

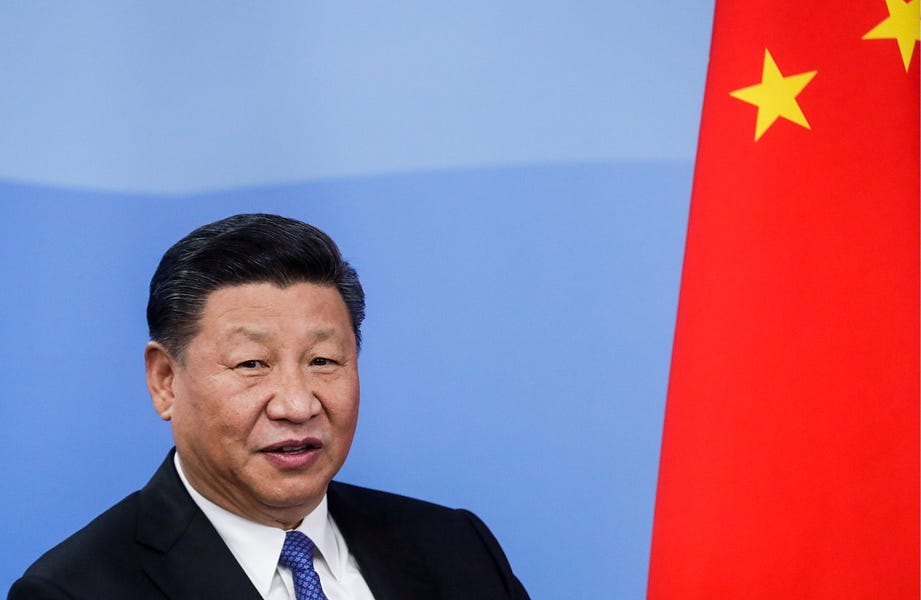

Photograph by Mikhail MetzelTASS via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.