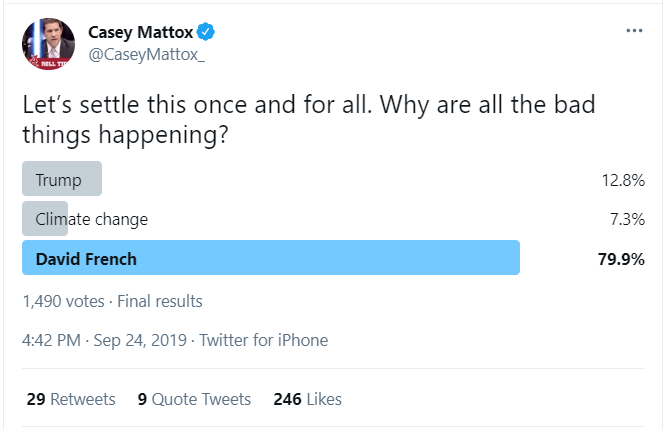

I used to have this running joke with my friend and colleague David French. Whenever there was some culture war travesty of the left’s making, or really whenever someone on the internet was wrong—which happens occasionally—I would blame David. It started when “Frenchism” was a thing. For those of you who don’t know, there are people on the right who think David embodies everything that is wrong with liberalism, “right liberalism,” “procedural liberalism,” free speech, the First Amendment, and even any form of Christianity that doesn’t take its cues from the CPAC crowd.

Of course, I was hardly alone. Type “Blame David French” into Twitter’s search engine and bask in the scapegoating.

I bring this up for a couple reasons. First, when it comes to moral and legal matters, there are few people whose opinion I value more than David’s. But when it comes to pop culture, his opinions can be so wrong (though not always, we agree on some things) that I start to wonder if the post-liberal integralists might have a point about him. He is a staunch defender of the Aquaman movie, writing, “Look, there are two types of people in this world—those who want to see a mass cavalry-charge of laser-shooting sharks and those who don’t. I proudly count myself in the former camp.”

Just so, I suppose.

Anyway, David has been on a tear of late, lionizing Zack Snyder, the Snyder cut, and the whole catalog of DC superhero movies. He’s even taken to doubling down on the crazy by describing Sonny Bunch as a “nearly infallible” pop culture guru, in no small part because Bunch has been a leading proselytizer of the Snyder oeuvre.

In the course of peddling so much muchness, David has been extolling Man of Steel, Snyder’s Superman movie, and the launchpad for the whole revamped DC extended cinematic universe.

Which brings me to my second point. Because of his relentless boosterism—including as a guest host of my own podcast!—I rewatched Man of Steel. And, well, I blame David French.

Don’t worry, this isn’t a review. But if you want to know what I think about Zach Snyder’s Superman reboot, which sets the stage for the larger Snyderian captivity of DC, (not the town) I’ll tell you. Actually, I’ll tell you even if you don’t want to know.

It’s okay. It’s all much, much, better than Aquaman. But puddle water makes for a better thirst quencher than strychnine, too. Also, David is surely right when he says, Man of Steel “was perhaps the most intensely serious Superman movie ever made.” I don’t think he needed the lawyerly “perhaps.”

As a movie, Man of Steel is better than a lot of the previous reboots, though I still like the 1978 Superman quite a bit. The acting is good. The action is good. The cinematography is a little annoying in parts, but it definitely holds your attention.

As for the writing? Eh. On the one hand, on its own terms as a superhero movie, it’s fine. I do think David—and Sonny Bunch—put way too much stock in Bunch’s Rosetta Stone explanation for the whole Snyder project. “The idea,” Bunch wrote in The Washington Post, “beginning with ‘Man of Steel,’ was a simple one: What would happen if gods appeared on Earth?”

I agree that would be a fascinating premise for these movies. I just don’t see a lot of evidence that’s primarily what’s going on—in any of these movies. Sure, it’s going on in Batman’s head, but there are no cults of Superman, no shouts of “The End is Nigh!”, no claims that Superman is the fulfilment of Fifth Monarchist prophecy.

Moreover, even if Bunch’s claim has massive explanatory power, it is nearly powerless to make these movies more enjoyable than they are—or, in the case of, Batman Vs. Superman, enjoyable at all.

With all that out of the way, let’s get to my problem with Superman and Snyder’s Superman.

Let’s start with Superman. The Kryptonian do-gooder has been a problem for DC for decades. He’s too powerful, too good, too handsome. This makes him boring, because without kryptonite, which got to be a tedious plot device from overuse, or magic, which is often a stupid plot device from the get-go, he was unbeatable. In itself, that’s okay. Lots of superheroes are ultimately unbeatable. But with Superman, the outcome is never in doubt. If it’s anything like a fair fight, he’s gonna win as surely as Godzilla will beat Bambi. Sure, you could kidnap people he loved and make him do stuff. But how many times can you write that storyline?

By the way, the original Superman wasn’t nearly so powerful as modern Superman. He couldn’t fly, he could just leap really high—“tall buildings in a single bound”—on account of Earth’s weaker gravity and his greater strength. But it didn’t take long for him to be able to hover, take sharp turns in the air, and even carry incredibly heavy stuff while doing it. In the 1970s his powers, which had mostly been increasing steadily from 1938 onward, were scaled down. But he kept getting more super. In the 1980s John Byrne—one of my favorite writers and artists when he was at Marvel—tamped them back down again. But power inflation always kicked back in. But unlike with balloons and the money supply, there was never any natural limit he could reach. He was faster than the Flash, stronger than everybody, and—my biggest peeve—his breath wasn’t just super powerful, it was in effect a freeze ray, which makes no sense at all.

In many ways, Marvel comics was born as a response to Superman. Marvel’s heroes were flawed. Indeed, their powers are often seen as a curse. The Thing hated being a monster. Ghost Rider literally sold his soul to the Devil (or Mephisto to be more precise). The Hulk began as the Mr. Hyde to Bruce Banner’s Dr. Jekyll. Mutants were born with abilities, and sometimes deformities, that made them freaks and pariahs, and ultimately persecuted minorities that invited genocidal campaigns to wipe them out. Spider-Man had to learn that his powers were a moral burden (“with great power comes great responsibility,” marking him the first neocon superhero).

Meanwhile Superman was literally born perfect. There’s a great little speech at the end of the second installment of Kill Bill in which David Carradine has a fun take on Superman:

Superman didn’t become Superman. Superman was born Superman. When Superman wakes up in the morning, he’s Superman. His alter ego is Clark Kent. His outfit with the big red “S”, that’s the blanket he was wrapped in as a baby when the Kents found him. Those are his clothes. What Kent wears—the glasses, the business suit—that’s the costume. That’s the costume Superman wears to blend in with us. Clark Kent is how Superman views us. And what are the characteristics of Clark Kent. He’s weak… he’s unsure of himself… he’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race.”

I don’t entirely buy this. Clark Kent isn’t a critique of the human race. But it does get at the problem with Superman. He’s too perfect, physically and morally. He’s a good-goody, and goody-goodies aren’t cool.

Forbes’ Dani Di Placido makes that case well:

And that’s the thing about Superman; he’s not cool. He’s not funny. He’s not edgy. Unlike Captain America, he was never one of us. Like Wonder Woman, he is meant to be a beacon of hope in a dreary world. But he’s significantly sillier than Wonder Woman, just as silly as Thor and Shazam, but unable to pull off the irony.

I dissent on the claim that Thor is silly, never mind as silly as Shazam, who always struck me as the sort of dude who needed to spend a decade in prison for a crime he didn’t commit, just to give him some personality. But he’s got a point.

Which brings me to the problem with Man of Steel.

As regular readers of mine know, I have a number of critiques of modern society. We think that people should be, in effect, their own priests. The ultimate arbiter of right and wrong is our own gut, our own instincts. Be true to yourself. Be authentic. Trust your instincts. We shun the admonitions and constraints of bourgeois morality and bourgeois institutions in favor of the romantic demand to be “authentic.” Indeed, in popular culture, we tend to cheer the authentically evil while we scorn the inconsistently good. Decent character isn’t measured by how much you conform to some external notion of right behavior, but how much you adhere to the inner voices of who you think you are.

People who try to make you bend your wants and desires—even whole communities—are the villains and the hero is the guy who Byronically sticks to his own code. We root for Dexter the serial killer because he sticks to a code (that allows him to kill only other serial killers, except when non-serial killers get in his way). We loved Hannibal Lecter even though he was as close a human being can get to being a literal monster. Indeed, we later learn in the sequels and TV show, that Lecter was wronged as a child as if the explanation is a substitute for the excuse. The original Grinch Who Stole Christmas was one of the greatest adaptations of Christianity-infused morality in popular culture. A beast, with a heart three sizes too small, is redeemed by the goodness of the Whovillians, the kindness of a child, and the Yuletide spirit. When they made the Jim Carrey version of The Grinch Who Stole Christmas (narrated by Anthony Hopkins in his Lecter voice no less), the Whovillians were the villains because they were intolerant of the Grinch for being different.

So, with that all out of the way, let’s take a look at Superman and Man of Steel. Back when Superman was indisputably the most popular superhero in the world, he was still a goody-goody. But he also bent his character to a cause larger than himself—America. Specifically, truth, justice and the American way. His upbringing in Kansas—the American heartland—was central to his story. Like a reverse Moses, he was cast out on an interstellar basket not to be adopted by some modern pharaoh but by a family straight out of a Normal Rockwell cover for the Saturday Evening Post. He fought in World War II, though less than you might think — DC worried that seeing Superman make short work of the Third Reich would be demoralizing. His aw-shucks patriotism and old-fashioned Midwestern decency defined him.

Fast forward to the post-1978 reboots. That kind of thing had gone out of style. Superman became cosmopolitan. As Peter Suderman wrote about Superman Returns, this Superman “seems embarrassed by its hero’s unashamed patriotism. Any hint of American exceptionalism has been trimmed away, leaving Superman as a generically postmodern world hero of no particular nationality. Gone are the backgrounds of notable American imagery; there are no flags, no monuments, no glimpses of the Capitol or the White House.”

“No,” Suderman continues, “instead of Superman framed against a waving flag, the new film’s most prominent image is of Superman hovering above the Earth, eyes closed, using his superhearing to listen to the cries of the world. News reports embedded in the film inform us of his globe-trotting ways, making sure to note his appearance in a variety of foreign locales, as if pre-emptively to clear him of the presumed arrogance of being America-centric. The message is clear: Once a hero for America, he has become a savior for the world.”

Snyder’s Man of Steel fixes some of these problems at the edges, but the core problem remains intact.

In one scene, Kal-El (Superman’s Kryptonian name) is talking with his dad Jor-El (technically an AI recreation of him). “You’re as much a child of earth now as you are of Krypton,” Dad explains. “You can embody the best of both worlds.”

We never get to see much of what was so great about Krypton, though. When we’re introduced to it, it’s a bleak, cold, eugenic dystopia literally coming apart at the seams. But whatever. “The people of earth are different from us, it’s true,” Jor-El goes on. “But ultimately I believe that’s a good thing. They won’t necessarily make the same mistakes we did, not if you guide them, Kal. Not if you give them hope. That’s what this symbol means …” He says, referring to the “S” that once stood for Superman but long ago was retconned as a family sigil. “Embodied within that hope is the fundamental belief in the potential of every person to be a force for good. That’s what you can bring.”

So, Superman isn’t a symbol of American moral might. No, he’s a symbol that if everyone looks deep enough inside themselves they can be super, too. Rather than Superman’s mission being to uphold the external values of his adoptive country—and parents—it is to prove that, you too, can be all you can be if you’re true to yourself.

Even his human mom agrees. Martha Kent tells him, “When you were a baby I used to lay by your crib at night, listening to you breathe. It was hard for you, you struggled and I worried all the time.”

Clark replies, “You worried the truth would come out.”

“No,” Martha replies. “The truth about you? You were beautiful, we saw that the moment we laid eyes on you. We knew that one day, the whole world would see that. I’m just…I’m worried they’ll take you away from me.”

Wait why’s that? Babies are civilizational sponges. Raise them wrong and they turn out bad, a point SNL made to great effect when it asked, What if “Superman Grew Up In Germany?” Now, the only yardstick of Superman’s rightness is how well he sticks to his own truth.

Contrast this with Captain America, a superhero who’s equally goody-goody and uncool. He can play by his own rules, too, as we saw in the Civil War chapter of the Avengers movies. But Captain America’s notion of what is good conforms to something greater than himself—his adherence to the best version of America. The modern Superman has more than a touch of Nietzsche’s superman: ultimately he’s transcended external notions of conventional morality and is guided by the truth stemming from his own innate superiority-from-birth and constrained by nothing other than his own will and conscience. He’s what we can all be if we embrace who we already are. It’s a treacly form of self-worship married to global messianism. He’s not Diogenes in a cape, a super-citizen of the world, he’s a metaphor for romantic self-worship. That’s an easier message to sell in overseas markets than Truth, Justice and the American Way.

Snyder seems aware of this problem. At the end of the movie, Superman destroys a drone that is surveilling him and dumps it at the feet of a U.S. Army general—an entirely reasonable thing for people dedicated to protecting America.

General Swanwick: Are you F-ing stupid?!

Clark Kent: That’s one of your surveillance drones.

General Swanwick: That’s a twelve-million dollar piece of hardware!

Clark Kent: It was. I know you’re trying to find out where I hang my cape, you won’t.

General Swanwick: Then I’ll ask the obvious question. How do we know you won’t one day act against America’s interests?

Clark Kent: I grew up in Kansas, General. I’m about as American as it gets. Look, I’m here to help, but it has to be on my own terms. And you have to convince Washington of that.

So there you have it. Sure, Superman’s one of the good guys. He likes America well enough. He was born in Kansas, after all. But he’s going to do good as he sees it, true to himself and “on my own terms.” Don’t like it silly soldier, fine. No one—and no thing—is the boss of me.

David likes to say that when it comes to pop culture, he’s “a fan, not a critic.” Fair enough, but embracing fandom, to paraphrase Friedrich Hayek, is a way to let the popular culture drag you along a path not of its own choosing.

I am sure a great many readers feel the same way having gotten this far into a circuitous essay on a slightly-better-than-ok superhero movie that came out eight years ago. I feel your pain. But think of this way: You, too, can blame David French.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.