How to Make Romney’s Family Security Act Even Better

Though it got buried in an avalanche of more pressing news—Supreme Court decisions, mass shootings, the January 6 hearings, and more—the release of the “Family Security Act 2.0” by Sen. Mitt Romney, along with fellow Republicans Richard Burr and Steve Daines, might turn out to be one of the most significant occasions of 2022, at least as far as American social policy is concerned. As the American Enterprise Institute’s Yuval Levin and Scott Winship wrote in National Review, “the new proposal advances the two core goals shared by all on the right who have been engaged in this debate: support for Americans looking to build families and support for Americans looking to rise out of poverty.”

At this point, to be sure, it’s just a proposal—and Capitol Hill today offers few paths to passage, even for popular ideas. Yet, as Ramesh Ponnuru explains, the fact that the outline has attracted support from large parts of the GOP coalition means it could and should serve as the starting point for bipartisan negotiations for a new federal investment in families. Unlike the expanded child tax credit that was a cornerstone of President Biden’s short-lived American Rescue Plan—which pulled millions of children out of poverty for the year it existed—this policy just might stand the test of time.

Romney’s new plan would provide all but the wealthiest families with $350 per month per child under age six, $250 per month per school-age child, and $700 for each of the last four months of pregnancy. That adds up to real money; a family with two small children would be looking at an $8,400 annual supplement to their income. It also eliminates marriage penalties baked into existing anti-poverty programs, and maintains a work-requirement to ensure that the country doesn’t return to the state of affairs before welfare reform. It is also fiscally responsible, funding the new family benefits by consolidating or eliminating several existing federal programs and tax breaks, including the state and local tax deduction. All of this is laudable, but allow me to offer one big amendment: The proposal should go much further in front loading its support to families with the youngest children. Specifically, it should provide $700 per month per child 5 and under. That’s twice Romney’s offer. Lawmakers could make the math work by reducing support for older children to, say, $150 per child per month (instead of $250), and/or by phasing out benefits for upper middle class parents.

The reason to focus on families with infants, toddlers, and preschoolers should be obvious to anyone who’s been a parent: Those are the most financially challenging years, both because parents of young children tend to be younger themselves, and thus poorer, and because public support for young children is much lower than once kids hit kindergarten. Indeed, ask any middle class parent what it felt like when their son or daughter entered elementary school, and the payments for preschool or childcare stopped or dropped precipitously. It’s like getting a big raise.

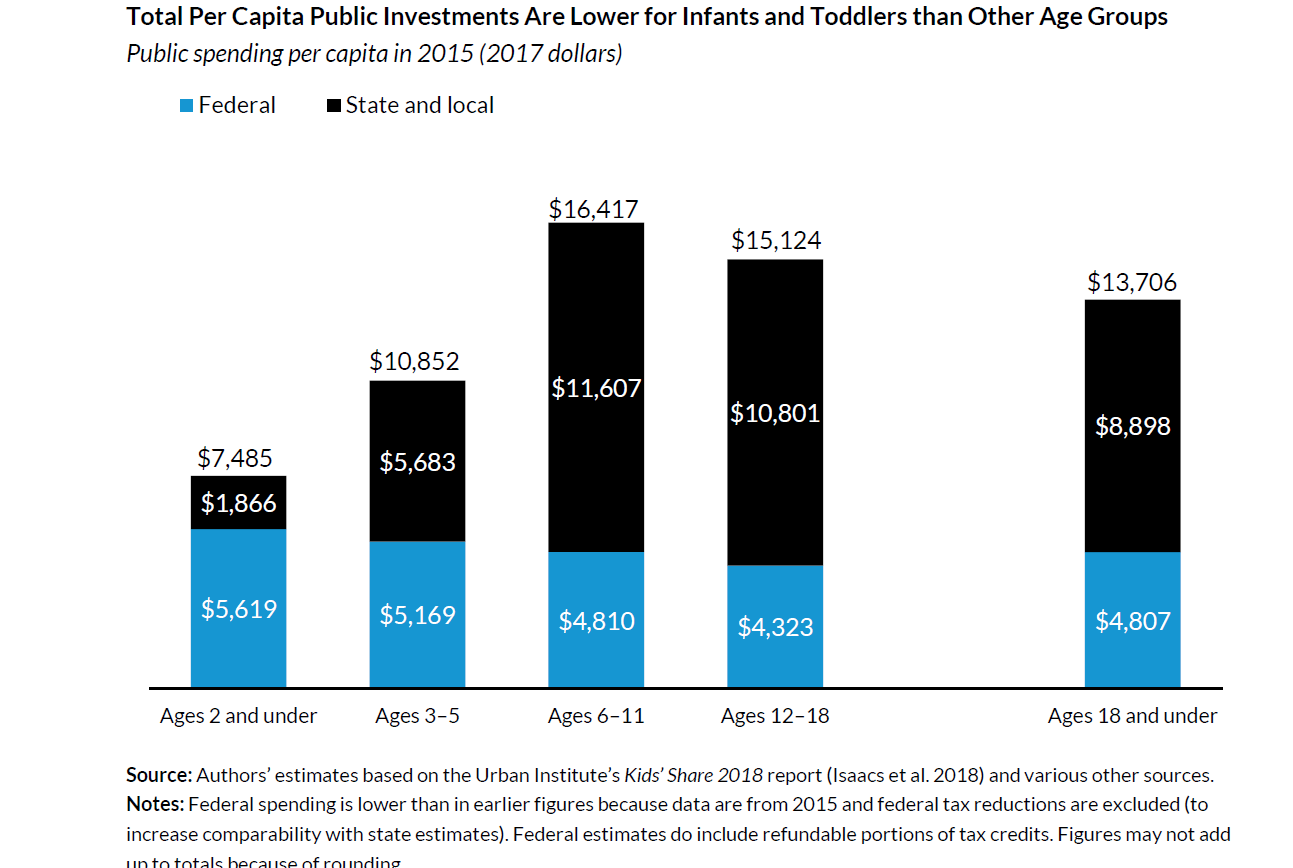

Taxpayers already make a huge investment in kids once they turn 5—it’s called public education. (Including, in the school reform era, public charter schools, public support for private school scholarships, etc.) Consider these findings from 2015, the most recent data available, courtesy of the Urban Institute.

The U.S. spends more than twice as many public dollars per child on those of school age than on infants and toddlers. Partly that’s because public education is nearly universal; it’s common for even rich families to send their kids to traditional public schools. On the other hand, most public investments in young children are targeted at poor and working class kids. Still, that doesn’t entirely explain the difference. My own calculations based on Urban Institute data indicate that we spend at least two-thirds less on low-income babies and toddlers than on their school-age siblings.

That gap might have been bearable when virtually all families had two parents, one of whom stayed home, taking care of the kids, while the other worked for decent pay. But it makes raising young children extremely difficult for today’s low-wage workers, especially single parents. Consider: Even at $15 an hour, a single full-time worker only brings home $30,000 a year. Imagine trying to pay for decent child care, on top of everything else, on such paltry wages.

Which means these families have to get by with much less than they need to provide a supportive, relatively stress-free environment for young children and their developing brains.

That’s why the left has supported paid parental leave, generous childcare subsidies, and universal pre-K—all elements in Biden’s ill-fated Build Back Better plan.

Republicans (and Joe Manchin!) were right to resist those proposals, as each would have created expensive, complicated new federal programs and policies—Rube Goldberg machines that would have warped the childcare sector, led to preschool programs of questionable quality, and intervened with state and employer actions on parental leave.

But the GOP needs a counteroffer—and a more generous allotment for families with small children should be it. With $700 per child per month, more parents could afford to take a few months off work after childbirth. They could pay for better childcare and pre-K. And unlike the Democrats’ proposals, asking Uncle Sam to write a bunch of checks is a program the federal government could get right. Critically, such a policy could also make it easier for women with unplanned pregnancies to say yes to life.

No doubt, plenty of Americans—especially on the right—will resist a new entitlement for families, especially one as generous as I’m suggesting here. They will correctly point out that money isn’t everything. Too many children in this country suffer because of neglect or abuse, because their parents struggle with addiction, other mental health challenges, or garden-variety dysfunction. To the extent that these challenges are present more often in poor and working class communities, extra money for families is no panacea.

But a simple return-on-investment analysis indicates that it would still be money well spent. America needs more babies to keep the economy growing. And babies’ brains need a healthy environment, especially in the early years, if they are going to get the most out of the almost $200,000 per child we then invest in them from kindergarten through high school graduation.

As pediatric surgeon Dana Suskind argues in her new book, Parent Nation, a growing body of research indicates that, just as poverty can inhibit healthy brain development in infants and toddlers, financial assistance can help to overcome the challenges. Studies led by Kim Noble, for example, use cutting-edge technology to measure brain waves and the structure of the cerebral cortex. Such measures can detect differences between 1-year-olds based on the socio-economic status of their parents. Other studies have found that material deprivation can impact children’s language, executive function, and memory. But as pilot studies show, cash payments to low-income families with small children can help kids (and their brains) overcome these challenges, at least to some degree.

As Romney, his colleagues, and advocates continue to make the case for additional investments in families, they should be clear-eyed about the goal. While extra help for school-aged kids is a fine thing, support for their younger siblings is a must-do. Front-loading support for the little ones will help Romney’s plan live up to its full potential—and will help America’s next generation to live up to its full potential, too.

Michael J. Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution