No, We Shouldn’t Cancel Our Debt With China

China has faced no small degree of scrutiny for its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic—the way it has stifled press freedom and tried to silence medical professionals who spoke out early on, the way it has engaged in propaganda and tried to deflect blame—and it’s unquestionably deserved. But one response peddled by populist conservatives in the United States would have disastrous ramifications, economists warn.

Some Republicans have let their frustration with the Chinese Communist Party push them into embracing fringe policies such as “cancelling” the $1.09 trillion debt our government owes to China. “If the U.S. did anything to impair the liquidity of treasuries and have them stop being the gold standard of the financial system, it would make this crisis look like chicken feed. It would be a collapse of the global financial system, the onset of something worse than the Great Depression” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, an economist who is president of the American Action Forum.

So how did the idea come about and who’s pushing it?

Back in April, Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina floated it in numerous television interviews. “China needs to pay,” he said on Fox News. He argued that it’s time to start “canceling some debt that we owe to China, because they should be paying us, not us paying China.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, just a few days later the Washington Post reported that several administration officials were pushing the idea behind the scenes in the White House. However, the report notes that President Trump himself has not publicly supported defaulting on Chinese-held debt.

Still, some conservative intellectuals are backing the idea. For example, UC-Berkeley law professor John Yoo has called for punitive debt defaulting.

“Washington could even cancel Chinese-held treasury debt and [use] the proceeds to create a trust fund that would compensate Americans harmed by the pandemic,” Yoo wrote in an op-ed titled “How to make China pay for COVID-19.”

And in the American Mind, a publication of the conservative Claremont Institute, Gunnar Gunderson argued the tactic could punish China at the same time it helped Americans.

“Cancel all American debt held by the [Communist Party of China], whether by the Chinese government or companies controlled by them,” he wrote. “That is debt we can finance with someone else and use the money to give relief to Americans who need it and to bring manufacturing home.”

“This is not a situation where we are just cancelling debt we do not want to pay—which would cause a credit crisis,” he continued. “Instead, this is the price of lying to America and the world about a global pandemic.”

These arguments are emotionally compelling. That might be why, at least somewhat, they’re catching hold: In a recent poll, 32 percent of the public supported refusing to make interest payments and therefore intentionally defaulting on the debt our government owes China.

As alluring as the urge to punish China might be, economists warn that there would be dire consequences.

Holtz-Eakin predicted that many nations who hold our debt would grow worried that the U.S. might renege on its obligations to them the next time they earned the American government’s ire. He explained that this would likely lead to a massive dumping of U.S. treasuries and a massive financial market shift toward another nation’s offerings, such as German bonds.

“You shouldn’t even breathe that you’re interested in [canceling the debt],” he said. If we ever did it, “Interest rates would skyrocket, our credit rating would go to mud.”

“Congratulations, you made China pay and you made us pay even more,” he continued. “You have crushed everyone in the interests of ‘payback for China.’ If you believe there’s an appropriate penalty that China must pay … don’t shoot yourself in the foot. Find another way.”

These concerns were echoed by economist Jonathan Bydlak, the director of the R Street Institute’s Fiscal and Budget Policy Project.

“The most obvious implication is that the ability of the U.S. to borrow would evaporate overnight,” he said. “Not only would China be unwilling to lend to the U.S., but other major lenders like Japan would likely interpret nonpayment as a risk to them, too.”

“Businesses and individuals would find it much more difficult to borrow, and the market would likely collapse due to the increased uncertainty,” Bydlak warned. “Not to mention, the U.S.’s standing in the world economic system would be forever shattered, since a significant part of our economic might has been built on our economic credibility.”

Not only that, but it would immediately impose massive costs on taxpayers, according to Cato Institute Economist Chris Edwards.

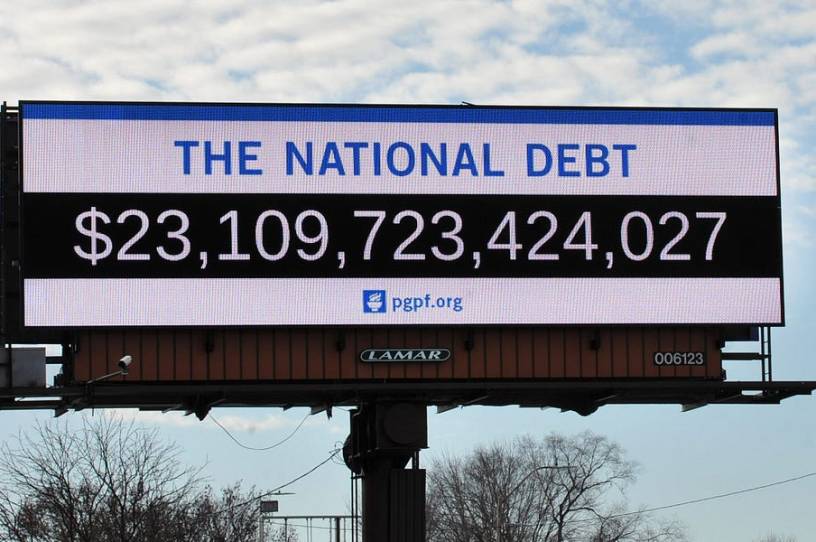

“Defaulting on federal government borrowing would be a neon sign that America can’t be trusted, and it would push up government borrowing rates on its $20 trillion in debt as it rolls over in coming years,” he told me. “The cost would ultimately land on U.S. taxpayers, who would be forced to pay higher interest costs for government debt.”

Edwards says that we have to get our budget under control if we want to reduce the debt we owe to China over time: “The U.S. government borrows so much from China because of the enormous fiscal irresponsibility of Democrats and Republicans over the past 20 years.”

Brad Polumbo (@Brad_Polumbo) is a libertarian-conservative journalist and fellow at the Washington Examiner.

Photograph by Michael Brochstein/Echoes Wire/Barcroft Media/Getty Images.