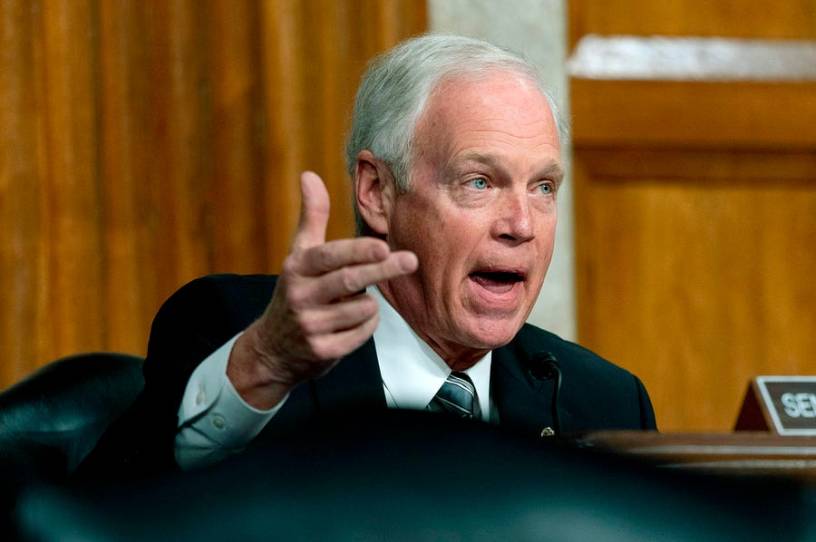

Ron Johnson Is the Same as He Ever Was

In August 2010, Wisconsin U.S. Senate candidate Ron Johnson sat in front of a microphone, ready to record a response to an attack ad by his opponent, incumbent Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold.

Earlier that week, Feingold had seized on a comment Johnson had made in which he said he was open to the “licensing” of guns “like we license cars and stuff.” Of course, gun owners are steadfastly against gun “licenses,” so Johnson quickly tried to defend himself, saying he supported “permits” to carry concealed weapons, not licenses.

“In my first days as a candidate, I used the wrong terms when discussing my strong support for concealed carry rights for gun owners here in Wisconsin,” Johnson said into the microphone. “ I’m not a slick politician, and I made a mistake.”

“It wasn’t the first time, and it probably won’t be the last.”

It wasn’t.

Johnson went on to defeat Feingold in 2010, then again in 2016. In recent months, he has risen to national prominence by promoting baseless, dangerous conspiracy theories on everything from the coronavirus vaccine to election security to the January 6 attacks on the U.S. Capitol.

Americans who have only recently heard of Johnson are likely surprised that he has flown under the radar for so long. But Johnson’s decade-long journey from private citizen to conspiracy-spouting Trump stand-in mirrors the populist sojourn of the Republican Party itself.

Johnson rode into office in 2010 on a wave of anti-intellectualism sparked two years earlier by GOP presidential candidate John McCain’s selection of Gov. Sarah Palin to be his running mate.

The Tea Party movement that rose up in 2009 inspired a slate of unserious candidates with little government experience to run for office. Christine O’Donnell in Delaware and Sharron Angle in Nevada became national laughingstocks and lost winnable seats; Rand Paul in Kentucky won despite saying he would roll back certain portions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Soon, Republican voters would come to consider Herman Cain, Michele Bachmann, and Donald Trump serious presidential contenders.

And Johnson, despite his difficulties with basic traditional campaign issues, became the only Republican in 2010 to beat an incumbent Democrat—a three-termer, to boot.

But the plastics manufacturer frequently confounded his campaign staff by refusing to speak ill of British Petroleum, whose oil rig was belching oil into the Gulf of Mexico for weeks on end. During one closed door meeting, his advisers asked Johnson to tone down the BP rhetoric. “I will not stop defending the producers of America,” he told them.

When he later visited the editorial board of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, he was asked about climate change and famously responded, “It’s far more likely that it’s just sunspot activity or just something in the geologic eons of time,” adding that be believed excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere “gets sucked down by trees and helps the trees grow.”

Before that editorial board visit, Johnson’s staff spent 10 hours preparing him and at no point had sunspot activity been addressed. “Excess carbon gets sucked down by the trees and helps them grow,” one staffer told me at the time. “He’s essentially saying pollution is good for the environment. Think that’ll sell?”

Johnson’s gaffes became national news. Jon Stewart joked on The Daily Show that Feingold was going to lose “to some guy who thinks global warming is caused by sunspots and toaster ovens.” The Onion ran a satirical column supposedly by Johnson boasting of his lack of knowledge, titled “My Opponent Knows Where Washington Is On A Map; I Don’t, And I Never Will.”

On the campaign trail, he used the economic term “creative destruction,” implying that people had to lose their jobs to factories overseas in order to create new jobs here in America. He said that “poor people don’t create jobs.” And he expressed his opinion that people should be able to get their primary health care at Walmart.

Late in the campaign, Johnson expressed frustration to Politico’s Jim VandeHei over his campaign staff “handling” him and coaching him to say more palatable things. “So he watches his words, ignoring the fact that he’s already making the trade-offs conventional politicians make to win office,” wrote VandeHei, a Wisconsin native. “It will be different once and if he wins, he promises. Then, his true feelings can take voice.”

A decade later, Americans are witnessing Johnson’s “true feelings.” He recently downplayed the siege of the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters, admitting he would have been more afraid had the mob been Black Lives Matters protesters. He has continually pushed debunked alternate treatments for COVID-19 and said he wasn’t interested in getting the vaccine because he had already been infected. (The CDC recommends people who have already had the coronavirus get vaccinated.)

In the waning weeks of 2020, Johnson spent weeks pushing the lie that voter fraud may have stolen the election from President Donald Trump. Over the past year, he used his Senate committee to investigate whether Joe Biden’s son Hunter received improper benefits from Ukraine while Biden was vice president—a charge a recent report suggests may be pro-Trump Russian misinformation.

But as Johnson’s struggles have shown, it’s not Johnson who has changed—it is the framework of incentives within the Republican Party that reward outlandish nonsensical declarations.

If anything, Johnson likely feels he has been vindicated by ignoring the political professionals—he won trusting his own conscience in 2010 and 2016, and the adviser in his own brain is now telling him to lean hard into baseless theorizing. He has morphed from anti-intellectual to aggressively MAGA in the same way the party has—one imagines that if GOP voters decided Republicans should start dressing like vampires, Johnson would be first in line to buy plastic teeth at the costume shop.

Yet perhaps most interesting is what will happen to Johnson in the near future. He once indicated he would not run again in 2022, but has since backtracked on that pledge. In early March, he said not seeking a third term is “probably my preference now,” but added a Wisconsin-sized caveat, saying his pledge was “based on the assumption we wouldn’t have Democrats in total control of government and we’re seeing what I would consider the devastating and harmful effects of Democrats’ total control just ramming things through.”

Thinking people would naturally ask: If Johnson were actually going to keep his pledge and not run again, why is he so closely embracing the most fringe elements of the Republican Party?

Typically, one would expect senators freed from the political pressures of reelection to take the opposite lane and reject Trumpism and the dangerous lies it breeds. But Johnson has rushed into QAnon territory as if he will someday need their votes.

This sets up two equally dispiriting options: Either Johnson isn’t running again and he actually believes the paranoid ramblings of anonymous internet users, or he is running again and he thinks the fringe is now in charge of his party.

If he does run again, there’s no guarantee embracing the crowd that tried to overturn the results of a national election will pay off politically. In Johnson’s home state, a recent obituary for 81-year-old Carol Lindeen showed up in a local Madison paper that made an odd request. “In lieu of flowers,” Lindeen requested, “please make a donation to Ron Johnson’s opponent in 2022.”

In September 2010, Johnson opened up to me about the pressure of giving a politically correct answer when someone throws a microphone in his face and asks him a question.

“Sometimes you just say things,” he said.

These days, Ron Johnson says a lot of things. But every word out of his mouth may actually say more about his party than it does about the two-term senator.