The 1619 Project Book, a Pew Bible for a New Religion

“Origin stories function, to a degree, as myths designed to create a shared sense of history and purpose,” writes Nikole Hannah-Jones to open the final chapter of New York Times’ 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, a new book-length version of 2019 series that asserted that the true founding of America was the arrival of African slaves in Virginia the year before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth.

Certainly, every superhero-loving 6-year-old knows “origin stories” are important. If we didn’t know about the murder of his parents, Bruce Wayne would seem like a rich weirdo in a rubber suit. Sometimes national creation myths work for good: The Arthurian legends helped the ruling class of England be more chivalrous and noble than they otherwise might have been—certainly more than many of their continental counterparts. Sometimes for ill: The myth of Moscow as the “third Rome” and true protector of Christianity to this day helps drive and provide cover for the relentless territorial ambitions of the Kremlin.

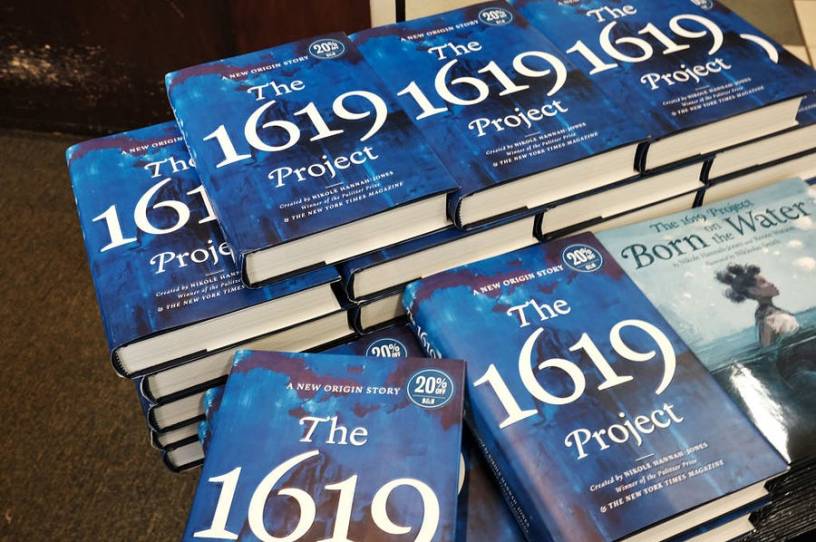

Hannah-Jones says that America’s creation story—the one that connects the freedom-loving colonists to the American creed of the Declaration of Independence to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to Martin Luther King’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial—has harmed her and other black Americans. The “erasure” as she called it in one recent interview, of the start of slavery from our national story has been evidence “of how history is shaped by people who decide what’s important.” In his introduction, the book’s editor, Jake Silverstein, says that the aim of the project, which now also includes this weighty tome, a children’s book, and a podcast, is no less than “to reframe American history, making explicit that slavery is the foundation on which this country is built.” Oh. Is that all?

Perhaps understanding how arrogant such an ambition sounds, and no doubt still smarting from the embarrassment of the gross historical failures of the project at its start, the book is kitted out with the trappings of scholarly work, including a kind of intramural peer review process and piles of footnotes that take the collection past 600 pages. But it is also very clearly built to be a new sacred text for the “elect” that John McWhorter describes in his new book Woke Racism.

The 1619 book never quite explains how “slavery is the foundation on which this country is built,” but it certainly takes dead aim at King’s idea of the “promissory note” of America’s founding that has for decades been at the center of our national identity. To do so, it enlists the author of one of the other sacred texts of the woke movement, Ibram X. Kendi, who warns against the notion of progress on race relations or for black Americans. I’m not sure how one could claim that progress is “mythical” in a country that elected as president the child of a mixed-race marriage just 41 years after miscegenation laws were abolished, but Kendi does. “Saying that the nation has progressed racially,” Kendi says, “has been used all too often to obscure the opposite reality of racist progress.” Racist devils want to lull you into believing that things are getting better, so don’t you dare give up on despairing.

In the first chapter, Hannah-Jones takes on the task of trying to create the “shared sense of history” to which the book aspires. The result was a lot of defensive-sounding finger wagging in response to the historians who had punctured the project’s initial premise that Americans rebelled against King George III because they wanted to protect legal slavery. For example, she cites an offer to slaves by British forces during the Revolutionary War for freedom in exchange for military service. But the revolution had already begun, so what’s her point? That it made Virginians very angry, and that our most important founders were from Virginia so … you know … it was a big deal.

Rather than absorbing the response from historians and returning with a more thoughtful and inclusive approach, like the one offered by Times music critic Wesley Morris, Hannah-Jones dismisses even the gentle reproaches of her kindest critics and barrels forward. But what else would you expect from someone who just last week declared, “They dropped the [atomic bomb on Japan] when they knew surrender was coming because they’d spent all this money developing it and to prove it was worth it. Propaganda is not history, my friend.” Dorm room denizens beneath halos of bong smoke would be embarrassed to offer such an insight, but Hannah-Jones is perhaps the most acclaimed journalist of her peers: a Pulitzer Prize, a MacArthur Foundation genius grant, and a Peabody Award just for openers. Having been affirmed by the intellectual establishment every step of the way, even when she was preposterously wrong, Hannah-Jones is not going to just suddenly develop humility and circumspection.

When she returns some 300 pages later to offer her summation, Hannah-Jones is ready to tell you what your new sense of purpose should be. The book that tries to pass itself off as a serious history closes with a political call to action, including “a livable wage; universal healthcare, childcare, and college; and student loan debt relief” as well as reparations payments to everyone who can “trace at least one ancestor back to American slavery.” If you do not agree or you have not absorbed this new “shared sense of history and purpose,” guess what you are? “[You] now have reached the end of this book, and nationalized amnesia can no longer provide the excuse,” she writes. “None of us can be held responsible for the wrongs of our ancestors. But if today we choose not to do the right and necessary thing, that burden we own.” You, the heathen, are still a racist if you do not see the light after reading the sacred text.

I’m about Hannah-Jones’ age and I too am a journalist who sometimes tries my hand at history. As I read her words and heard her complaining in interviews about the supposed coverup of slavery, I kept thinking how if her high school in Iowa had taught American history even half as well as mine in West Virginia, we might all have been spared this book.