The End of Humira’s Monopoly

Over the past 20 years, the biotech company AbbVie has raked in $200 billion in revenue just from sales of its drug Humira, an unprecedented amount in pharmaceutical history. Humira was initially approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis but later earned FDA approval to treat a host of inflammatory diseases.

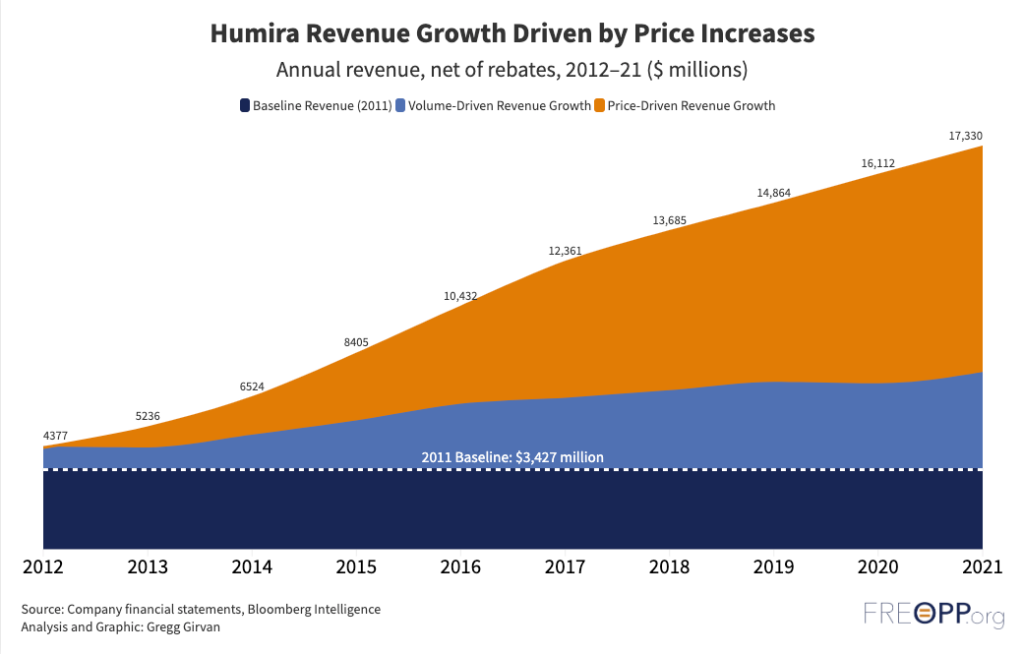

Now, finally, it has some competition. Amgen this week launched the first generic alternative—or biosimilar—to Humira (adalimumab). That it has taken two decades for this day to arrive is a stinging indictment of the failures of the U.S. drug market to provide life altering medicines at affordable prices. Humira’s monopoly was the result of congressional statutes and federal regulations, allowing Abbvie to raise list prices by 600 percent since the drug’s launch at $522 per 40 milligram syringe. Our analysis at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity shows most of Humira’s revenue came from price increases with little product improvement.

It will take congressional action to restore a competitive market for pharmaceuticals and prevent monopoly pricing on drugs like Humira in the future.

Biologics vs. pharmaceuticals.

To understand why Humira and drugs like it have enjoyed a substantial competitive advantage leading to runaway drug spending growth, you first have to understand that there are two categories of drugs sold under very different rules in the U.S.

Most people think of prescription drugs as tablets or capsules. These drugs, known as small molecule drugs, are relatively simple compounds synthesized in a laboratory. They are regulated under the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, championed by Rep. Henry Waxman and Sen. Orrin Hatch and so more commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.

But Humira is a biologic. These drugs are far more complex protein structures with substantially greater molecular weight, synthesized inside biological organisms rather than in beakers. They are often injected into the body through intravenous needles, syringes, or autoinjector pens.

Because of those differences, Hatch-Waxman did not apply to biologics. This is unfortunate, since Hatch-Waxman is a rare breed of federal legislation that actually improved the function of the private market. It set the conditions that encouraged drug companies to develop innovative and life-saving treatments while also increasingly bringing low-priced generics to market. Thanks in large part to that legislation, the U.S. leads the developed world in using generic drugs to provide low-cost treatments to more patients than ever. Today, 90 percent of prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. are generics. For comparison, many European countries dispense generics at a rate less than 50 percent, including Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Sweden, and Spain.

Only in 2010, with passage of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCI) embedded in the text of the Affordable Care Act, did Congress set the paradigm for biologics as Hatch-Waxman did for small molecules. There are substantial differences between Hatch-Waxman and the BPCI. First and foremost, Hatch-Waxman grants pharmaceutical companies five years of marketing exclusivity after FDA approval before generic competition is permitted. The BPCI, however, grants biologic drugs 12 years of exclusivity.

In addition, the BPCI set forth requirements for developing generic versions of biologic drugs. It is nearly impossible to produce an exact copy of an original biologic because of differences in processes and cell lines, so the BPCI requires biosimilars to undergo the same rigorous clinical trials as the original drug, significantly increasing R&D time and cost. In contrast, manufacturers must only prove that small molecules have the same molecular composition to achieve generic drug approval.

Drug companies use the BPCI’s provisions and the complexity of biologics to their advantage by building “patent thickets”—applying for multiple patents on a drug’s formulation, manufacturing, disease indications, and delivery methods to create an impenetrable wall of intellectual property around the drug. And since these patents were often hidden from public view prior to legislation passed in 2021, a competitor inevitably runs afoul against one of those patents when attempting to develop a biosimilar. Lawsuits are filed, biologic manufacturers win or obtain favorable settlements, and competition is stymied.

After Humira’s formula patent expired in 2016 the drug’s patent thicket consisting of 132 additional patents delayed Amgen’s biosimilar launch by more than seven years. Even now, Amgen and seven other competitors will launch at various dates this year and pay AbbVie royalties for the privilege.

Congress can take two steps here: First, it could harmonize the BPCI with Hatch-Waxman. Applying the same rules in Hatch-Waxman to biologics, will let biosimilars will enter the market more quickly to reduce prices while still encouraging the development of new treatments. And it should eliminate patent thickets so companies cannot use trivial patents to block competition.

Encouraging biosimilar success.

There are plenty of reasons to be optimistic, now that eight competitors are launching their own versions of adalimumab in 2023. The arrival of the first adalimumab biosimilars will undoubtedly lead to price drops on Humira itself as well as biosimilar competitors. Several health plans, including those from national insurance giants UnitedHealthcare and Aetna, expect lower net prices on Humira as well as a list price 15 to 35 percent lower for biosimilars.

The savings on biosimilars in the coming years is expected to be enormous. A joint study by the RAND Corporation and the Department of Health and Human Services projects that biosimilars will save $38.4 billion between 2021 and 2025, with more than half attributable to biosimilars of Humira. The IQVIA Institute expects even greater savings, with a base case of $181 billion in savings from 2023-2027.

Lower prices notwithstanding, concerns remain over viability of biosimilars, and Humira is likely to remain a blockbuster drug (i.e., sales exceeding $1 billion annually) for many years. That’s because AbbVie is likely to make further concessions with insurance plans and the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) that negotiate lower drug prices in exchange for preferred positions on a plan’s drug formulary, thereby squeezing out biosimilar competitors that are looking to recover their investments.

Whatever happens, the race for Humira’s market share is the biggest test of the U.S. biosimilar market to date, and will likely have repercussions on the willingness of drug makers to pursue other biosimilars in the future. On the one hand, manufacturers have been recovering their investments on adalimumab biosimilar sales since 2018, when their versions were permitted in Europe and elsewhere. Competitors have significant room to price their products below AbbVie’s price drop, even including royalties paid to AbbVie. On the other, the real concern should be whether biosimilars will be dispensed when a pharmacist receives a prescription for adalimumab.

There are a few lessons to be learned from Europe. Not only was the European Union ahead of the U.S. in forming its biosimilar approval framework in 2003, the European Medicines Agency (EMA, the EU’s version of the FDA) is also ahead of the U.S. in cutting red tape.

U.S. pharmacists can automatically substitute generics in place of brand name small-molecule drugs, but can substitute biosimilars only if they are interchangeable with the original drug. This means that not only do drug companies have to conduct randomized trials for biosimilars that are not required for generics, they have to conduct further testing to receive a special “interchangeable” designation. Last summer, the EMA declared that, from a scientific standpoint, all biosimilars are interchangeable with their original products, citing 15 years of review and monitoring that showed that “in terms of efficacy, safety and immunogenicity they are comparable to their reference products and are therefore interchangeable.”

Congress should require automatic substitution after a company demonstrates its biosimilar is manufactured in the same manner as the original biologic.

Lessons to be learned.

Biologics once represented a new frontier in disease management, and there were questions as to whether biosimilars could produce the same efficacy and safety outcomes, and whether companies could produce them cheaply enough to compete with originator companies.

Times have changed. Biosimilars are produced with greater ease and therapeutic equivalence than ever before. Yet the case of Humira shows that government policy lags woefully behind the science, to the benefit of large drug firms looking to suppress competition. Federal laws that create artificial monopolies and have nothing to do with innovation are preventing the development of competitive markets. Instead, we need legislation that eliminates patent abuses, applies the same exclusivity timelines to biologic as small molecule drugs, and makes automatic substitution a reality for biosimilars. Medicare and Medicaid payment reforms that drive patient and taxpayer savings would also foster greater competition and lower prices.

Large drug companies argue these reforms will inhibit the development of new treatments because they will have less opportunity to recover R&D investments. Here again, our research shows that these concerns are largely unfounded; it turns out new policies that lower R&D costs, rather than encourage higher prices, fuel innovation.

It is time for us to learn from the financial catastrophe of Humira’s 20-year reign and build a truly competitive drug market that is affordable for patients and fiscally sustainable for generations to come.