Newsletter

House Democrats Help Mike Johnson Tee Up Ukraine Aid for a Vote

Plus: What to watch for as arguments in Trump’s Manhattan trial begin.

An Early Morning Strike On Iran

Plus: After first-quarter data came in hotter than expected, the U.S. economy enters uncharted territory.

An Early Morning Strike On Iran

Plus: After first-quarter data came in hotter than expected, the U.S. economy enters uncharted territory.

How Trump’s New York Criminal Trial Might Play Out

Plus: A look at the former president’s media strategy.

House Releases Foreign Aid Bills

House Speaker Mike Johnson’s gambit to fund Israel and Ukraine could put his speakership on the line.

House Releases Foreign Aid Bills

House Speaker Mike Johnson’s gambit to fund Israel and Ukraine could put his speakership on the line.

The People Are Voiceless

In a democracy, voters never really speak with one voice—and they’re often wrong.

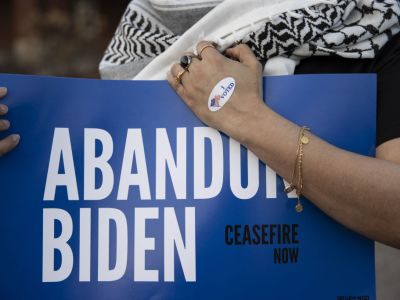

Joe Biden Faces Backlash From Arab American Voters

Plus: The president is in danger of being left off the ballot in two states in November.

U.K. Report Calls into Question Youth Gender-Transition Treatments

‘For most young people, a medical pathway will not be the best way to manage their gender-related distress.’