Dear Capitolisters,

Last week, I did a short hit on CNN regarding the current turmoil in U.S. financial markets and whether the economy is at risk of “overheating” this year. In the process of preparing for that appearance (and after receiving a few reader comments on the subject), I realized that the issue would make for a good newsletter topic—less issue advocacy and more explaining the current situation and where we might (keyword: might) be headed. So that’s what we’ll do today.

Where Things Stand Right Now

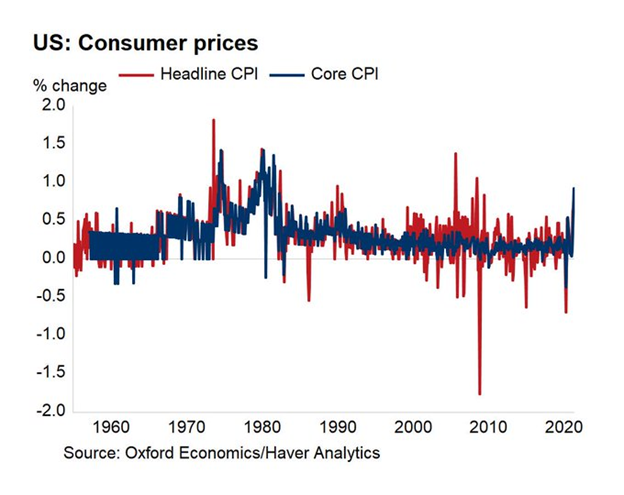

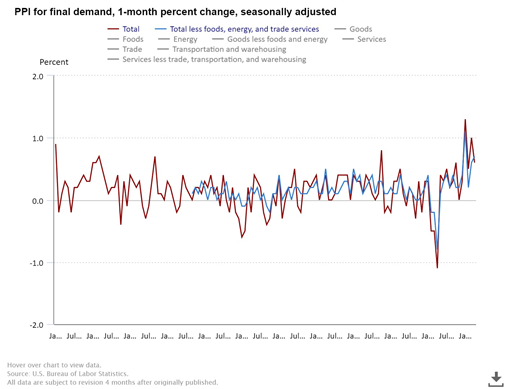

Both the U.S. economy and financial markets are—to use a technical term—really screwy right now. Supply chains (domestic and global) are stressed and companies are “panic buying”; unemployment remains extremely elevated, yet employers say they can’t find workers (even as they’re raising wages); and consumer and producer prices have spiked—especially in intermediate inputs (steel, lumber, chemicals, etc.), food and energy, and housing. And don’t even get me started about the craziness that is Dogecoin, or NFTs, or “meme stocks,” or … you get the idea. Anyway, we’ve covered some of this stuff in previous newsletters, and things have probably gotten a little more unstable following the release of April’s job numbers (lower than expected) and inflation data (higher than expected). On the latter front, both the consumer price index (CPI) and producer price index (PPI), which are intended to measure economy-wide price pressures, have both spiked significantly. Year-over-year comparisons are misleading right now because prices collapsed at this time last year (which makes annual gains appear abnormally large) but both monthly increases were also quite high—and, perhaps more importantly, well past economists’ expectations.

More recent data (and plenty of anecdotes) indicate that price pressures—potentially a harbinger of long-term inflation—are continuing this month. Stock and bond markets have thus been gyrating pretty wildly in recent weeks (especially the tech-heavy NASDAQ—the darker blue line in the chart below, when compared with the broader S&P 500 in lighter blue); politicians have started pointing fingers and sharing Jimmy Carter memes; and many people are left wondering if this is all a momentary, pandemic-related blip or something worse (i.e. Carter-era stagflation)—a question whose answer could have serious implications for future U.S. fiscal and monetary policy.

What’s Inflation?

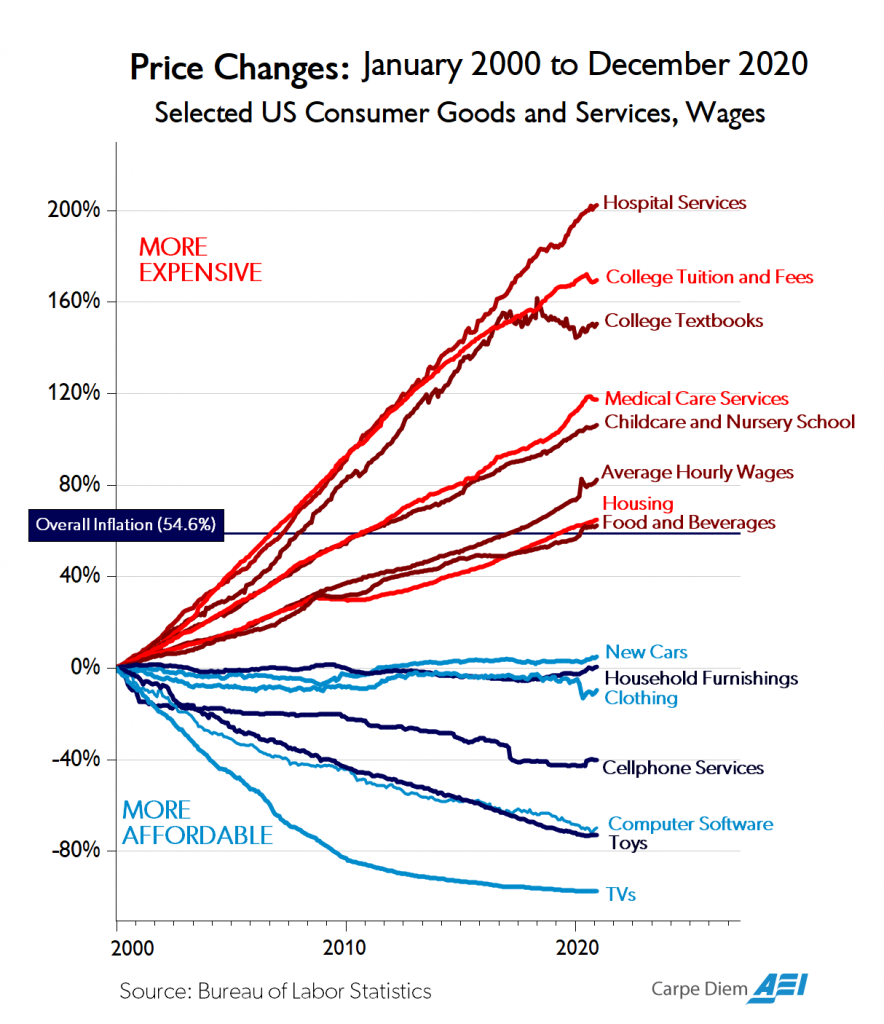

Before we get to what might be causing all of this, a quick, wonky note: “Inflation” is a broad measure of price increases across the entire U.S. economy—usually based on a “basket” of thousands of goods and services picked by the U.S. government (CPI from the consumer’s perspective, PPI from the seller’s). This definition is important, as you could see a strong increase in certain prices or places but overall low inflation nationwide because prices of many other things have remained flat or actually declined. Indeed, this very thing happened in the years following the Great Recession, with prices of certain things—particularly housing, education, and health care—rising quickly but overall inflation remaining at or below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target.

By contrast, today’s fears are that price increases are more widespread—i.e., the worry is less about isolated spikes in prices for things like lumber (though these things can hurt) and more about persistent increases in many goods and services that combined erode living standards and could spiral out of control.

So What’s Going On?

From my vantage point, there are four broad things causing the current turmoil, which basically boils down to a big and uncertain imbalance between supply and demand for all sorts of goods and services:

The pandemic, obviously: The global pandemic has hit markets in all sorts of ways. First, it wreaked havoc on domestic and global supply chains (shutting down businesses, closing ports, stopping travel, etc.) and changed consumer needs almost overnight (more medical goods, suburban housing, packaged food, remote work supplies, etc.; fewer business suits, restaurant and office supplies, urban offices and apartments, etc.). Thus, while suppliers were struggling just to get up and running again, some also had to retool their operations to meet the “new normal” demand (which takes time, especially during a pandemic!). Furthermore, companies didn’t know whether things would snap back to the “old normal” once the virus waned, confounding their ability to forecast both their internal needs (workers, raw materials, etc.) and external demand for their products. Semiconductors are perhaps the best example of this: Automakers thought demand for cars would plummet and cut back on semiconductor orders, only to be caught flat-footed when demand actually increased last year. But when they tried to re-up those orders, they discovered that chipmakers had retooled to address a spike in demand for electronics (video games, computers, smartphones) that homebound consumers wanted. And new capacity will take years to come online. You’ll find similar messes all over the place (e.g., lumber).

Second, pandemic-related stay-at-home orders and business closures, along with fear of the virus, curtailed American spending and put consumers in prime position to spend once the economy reopened. As we’ve discussed, for example, Americans are exiting the pandemic with record savings and less debt because they were stuck at home and many consumer-facing services were shut down. This “pent-up demand” is now getting released. (Woo hoo!)

Third, the pandemic also affected workers in all sorts of ways. For starters, the labor pool is probably smaller: Some workers died, retired early, or are suffering long-term effects from COVID and can’t get back to work (more on that here); some are still afraid to return to work; and others (especially working moms) can’t go back to work because their kids’ schools or daycares are still closed (though new research shows that the overall impact of school closures may be muted). Another issue is a mismatch between unemployed workers who are eager and able to return to work and the jobs that are open to them. For example, some workers may be trained in jobs that aren’t in demand where they live or are reconsidering their previous jobs (especially in consumer-facing retail and food service) and moving to new, safer and (maybe) higher-paying jobs in industries (warehousing, e-commerce, etc.) that actually benefited from the pandemic. All of these factors can – even without government policy (more on that in a sec) – throw sand in the labor market’s gears and cause quickly-reopening businesses to struggle to find workers.

Finally, the virus has receded – and economies have reopened – faster than many expected, as vaccines proliferated. As a result, all of that pent up consumer demand (Americans flush with cash) was unleashed on the market before many suppliers, investors, and policymakers were ready. (Not me, of course.)

Government policy: Government policy is certainly contributing to the current situation. For starters, the Federal Reserve took extraordinary action—well beyond just lowering interest rates to zero—to ease monetary policy and stabilize bond markets last year. However, as the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip noted recently, the Fed has continued these “abnormal” policies even as the U.S. economy is well on its way back to normalcy, with various Fed officials expressly (and repeatedly) saying they intend to let the economy run hot, and let various “transitory” (in their view) price spikes run their course, until we’ve achieved the central bank’s goals of full employment and 2 percent average inflation.

Fiscal stimulus, Ip notes, has followed a similar course: Democrats promised “emergency” trillions last year when the virus was raging and the economy mothballed, but they never changed course when the nation and virus did (even though it was clear in February that the crisis was all but over). Most notably, the American Recovery Plan injected hundreds of billions of dollars (without offsetting taxes) into an economy that was already revving up due to vaccines, declining cases/deaths, and previous trillions in government assistance. And, of course, Biden and congressional Democrats want to spend trillions more. Combine this with the monetary policy, and you get booming stock and asset prices.

The ARP’s stimulus checks and supplemental unemployment benefits, especially when combined with previous pandemic-related subsidies, have also probably discouraged some workers (who can make more from not working than working) from returning to work, further limiting the supply of available workers and putting even more upward pressure on wages. This was a possibility when we discussed it last month, and some effect is increasingly clear—as even many left-of-center folks now acknowledge. (See today’s Chart of the Week for more.)

Meanwhile, certain non-pandemic policies—tariffs on steel, aluminum, lumber, and Chinese goods; U.S. sanctions on semiconductor equipment destined for China; state occupational licensing, zoning, and other regulatory restrictions; etc.—are adding to the aforementioned macroeconomic pressures for key industries (housing/construction, semiconductors, autos, health care, etc.) I wrote about lumber recently, and now –coincidentally, I’m sure! – Congress is asking questions about it, too. The key point: These discrete policies aren’t causing inflation, but they can certainly restrict supplies, distort markets, and cause acute, price-related pain for specific U.S. industries. They’re essentially an economic own-goal.

Freak events: Then there have been several “freak” events that have exacerbated the aforementioned supply problems. This includes ice storms in Houston, the Colonial Pipeline hack, the Suez Canal debacle, debilitating fires at not one but two big Japanese semiconductor factories, a drought in Brazil, and several other unexpected shocks around the world have added to the aforementioned supply constraints.

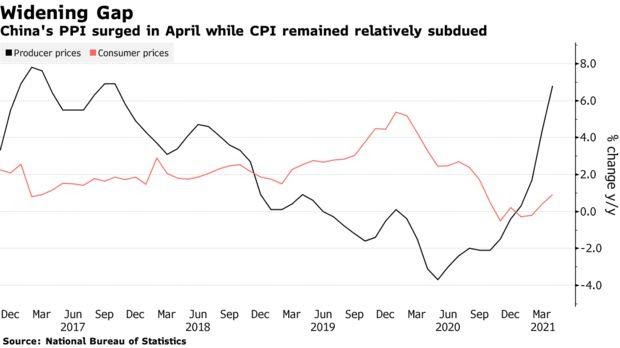

International stuff: Events abroad are the last ingredient to the current market situation. Beyond the obvious hiccups that localized events—pandemic-related or otherwise—can have on the production, distribution, and price of specific goods and services abroad, researchshows that globalization of supply chains, financial markets, and even economic theory (carried out by central banks) can globalize inflation too. When it comes to the U.S. market, this phenomenon can work both ways: countries like India (or, to a much lesser extent, Japan) that are still struggling to contain COVID-19 could depress global output and demand, but countries that are reopened and swimming in their own stimulus could do the opposite. On the latter score, it’s notable that China—whose imports used to lower U.S. prices—may now be exporting price pressures abroad: “With China being the world’s biggest exporter, its rising cost pressures for the nation’s factories pose another risk to global inflation as manufacturers start passing on higher prices to retailers.”

China also isn’t alone: producer prices are also up big in South Korea and Germany (and, of course, the United States too).

Put it all together, and you have tons of dollars chasing a still-restricted supply of goods and services, and a lot of uncertainty. Thus, we see higher prices (much higher in some cases), supply shortages, and tons of job openings and wage pressures even though unemployment is still high and many businesses are still closed. It’s—to use another technical term—a big mess.

So What Happens Next?

While everyone accepts short-term price craziness, the big question is whether these price pressures are transitory (as the Fed seems to think) or a harbinger of long-term inflation that hurts American consumers, undermines confidence in the Fed, and perhaps forces the central bank to cool off the economy by raising rates, thus slowing economic activity and risking a full-on recession.

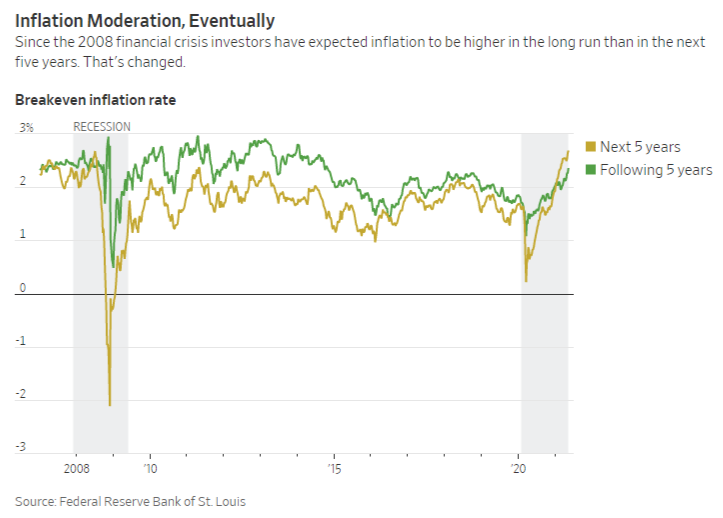

Even with recent wobbles, Mr. Market still thinks this is all transitory, and that supply and demand will adjust in the next few months (and government payments will slow), causing prices to stabilize in most sectors. In particular, inflation expectations remain around the Fed’s 2 percent target, and both long-term inflation expectations and commodities traders expect prices to cool next year.

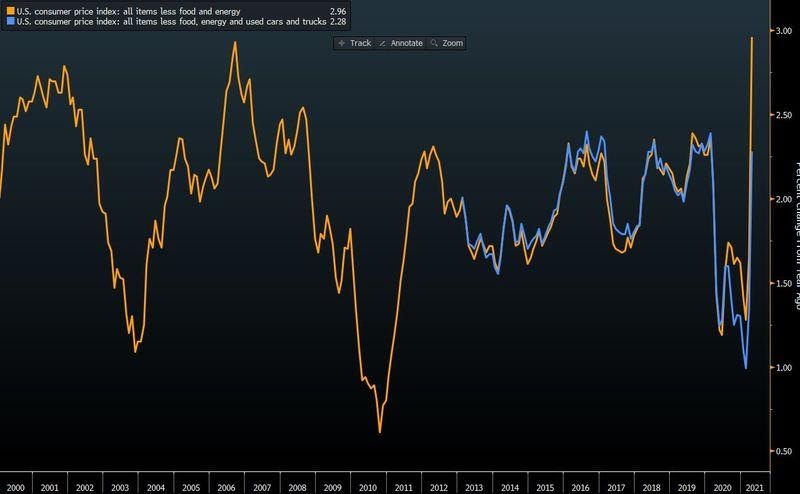

Even with eye-popping price increases and the expectations-beating April CPI/PPI figures, there is some justification for this view. In particular, a lot of the world is still unvaccinated (thus keeping global growth subdued); certain parts of the U.S. economy might not roar back (because of COVID casualties or still-cautious consumers, for example); and, as Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal shows, the April CPI figures were driven by spike in used car prices that may be short-lived (because rental car companies liquidated inventories and have now finished scrambling to refill them):

Finally, April’s very high CPI reading is just one month, while Vietnam-era inflation was months (and months) of the price increases—see first CPI chart above. Thus, it’s far too soon to say we’re entering an “inflationary spiral” based on the CPI/PPI data we have right now.

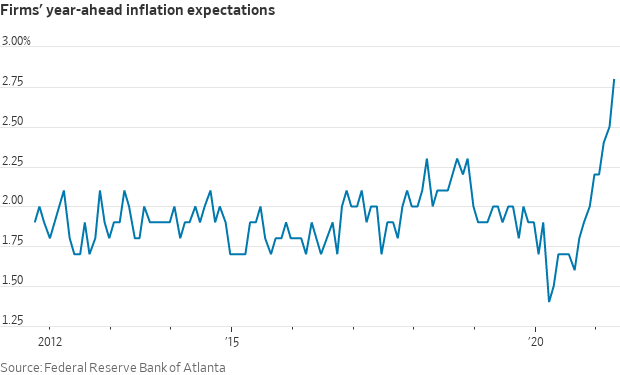

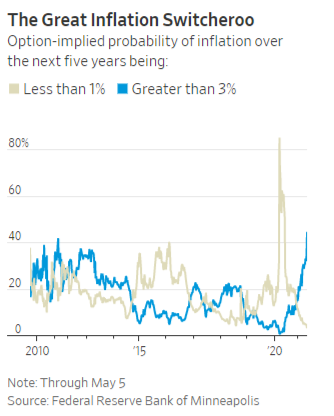

That said, there are some reasons for concern. First, Mr. Market keeps getting things wrong—overestimating labor market improvement and underestimating price pressures—mainly because the current moment (both the pandemic and the policy response) is so unique, and because investors trust the Fed. That said, even Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida admitted last week that he was “surprised” by the April CPI figures: “This number was well above what I and outside forecasters expected.” He maintains that things are under control, but his admission doesn’t exactly inspire confidence. Meanwhile, inflation expectations keep creeping up, and “investors are much less confident now than before the pandemic about their predictions of inflation”:

Furthermore, it’s unclear whether companies will actually increase supply to meet demand or whether other supply chain snafus are on the horizon. On the former issue, it certainly looks like semiconductor firms are going to invest a lot in new capacity, but producers of steel and lumber, for example, are resisting such moves, in part because of uncertainty about whether demand will continue into next year (and U.S. trade policy, which helps them profit-take). On the latter, there’s the small fact that the pandemic is still going on in many places around the world. So maybe, as AEI’s Michael Strain put it, the “one-off events” that inflation doves tell us to ignore… keep happening:

Any period of sustained inflation is likely to begin with aberrant economic phenomena. The pattern takes months to emerge. In April, a fluke in the semiconductor supply chain sent the price of used cars soaring. Maybe this will return to normal in May, but then a transportation problem could suddenly push up the price of meats and eggs. Imagine that June brings them back to earth, only to see the cost of children’s clothes going through the roof. July and August each have rapid price growth, as well, for their own quirky reasons.

Several months of “aberrant” data could cause investors to lose confidence in the Fed, abruptly change course, and take the stock and bond markets down with them. As former Fed official Brian Sack told the New York Times last week, “We aren’t obviously on the way to a very high and persistent inflation outcome. … But we’re at an inflection point, in that the rise in inflation expectations to date has been a policy success, but a rise from here could become a policy problem.”

The other big unknown is psychology: if Americans start to expect long-term inflation, this may actually cause it to occur. (Yes, this is, like, way deep, man.) In particular, rising inflation expectations can (1) cause Americans to “panic buy” now (fueling even more panic—see, e.g., housing right now) and (2) permit producers to raise prices because they know consumers are expecting it (and thus won’t resist). Strain again:

The relevant issue isn’t whether one-off factors explain any one month’s data. Instead, the question is whether the accumulated effect of several months of price spikes — each driven by unique factors — leads consumers, workers and businesses to change their expectations about the pace of future price increases.

At some point, workers might have lived through enough months in which temporary factors drove up the price of a handful of goods or services that they knock on their boss’s door and demand a raise. At some point, businesses might have had one too many one-off hikes in the cost of things they need that they raise the price of what they’re selling.

How this all plays out is anyone’s guess at this point, but public concern is rising. And, as I joked on Twitter the other day, Americans just recently showed that they get kinda nuts when markets go awry and the cable news machine gets rolling:

If inflation really does start to kick in, the Fed could be in a tough spot: Either let higher prices erode wage gains (especially for lower-income Americans with little disposable income), boost inequality, and hurt investors, or raise interest rates to cool things off and stop a debilitating inflationary spiral before it starts. Higher rates mean higher borrowing costs and eventually less spending, which in turn lowers domestic demand for goods and services. This causes inflation to decline but can also cause a full-blown recession—especially if unprepared markets freak out at the extent of any rate hike. Meanwhile, investor confidence in the Fed will be in tatters, further undermining future economic growth and stability.

We are certainly not there yet, and the safe money is probably on us never arriving. (New data show that commodities prices may have peaked.) But, as we discussed in February, a lot of smart folks—including some on the left—are concerned, especially in the wake of trillions of dollars in new and proposed government spending. And the outcome depends not only on the data, but also on events outside the United States and on individuals’ feelings (about COVID, inflation, their previous jobs, etc.). Thus, while the risk may be low, it’s just crazy to pretend that there’s no risk at all. Fortunately, we’ll know more soon, as additional jobs and price data, as well as lots of anecdotal evidence of supply and demand adjusting (or not!), roll in.

Hopefully by then it won’t be too late.

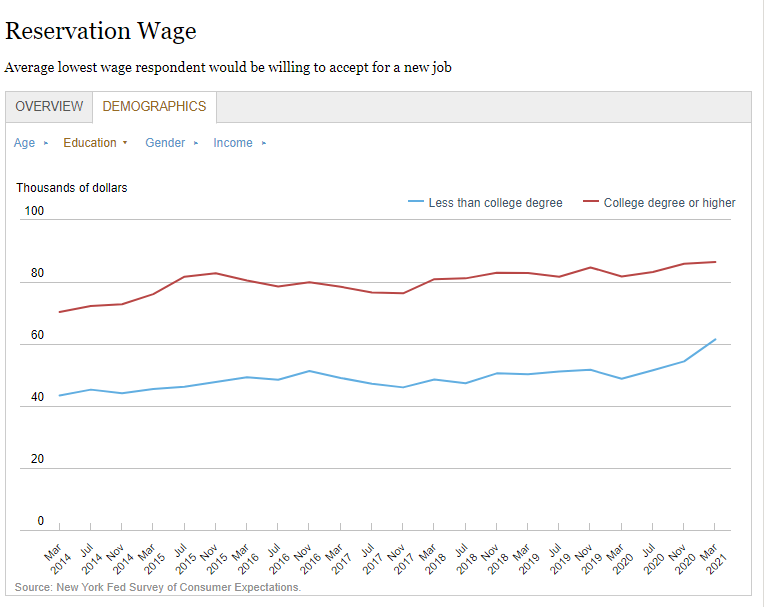

Chart of the Week

Per Jed Kolko, The self-reported “reservation wage” (the lowest wage a worker is willing to accept for a particular job) is up 26 percent since last year for workers without a college degree. The annual gain averaged only 2 percent over the previous six years.

Bonus Chart of the Week

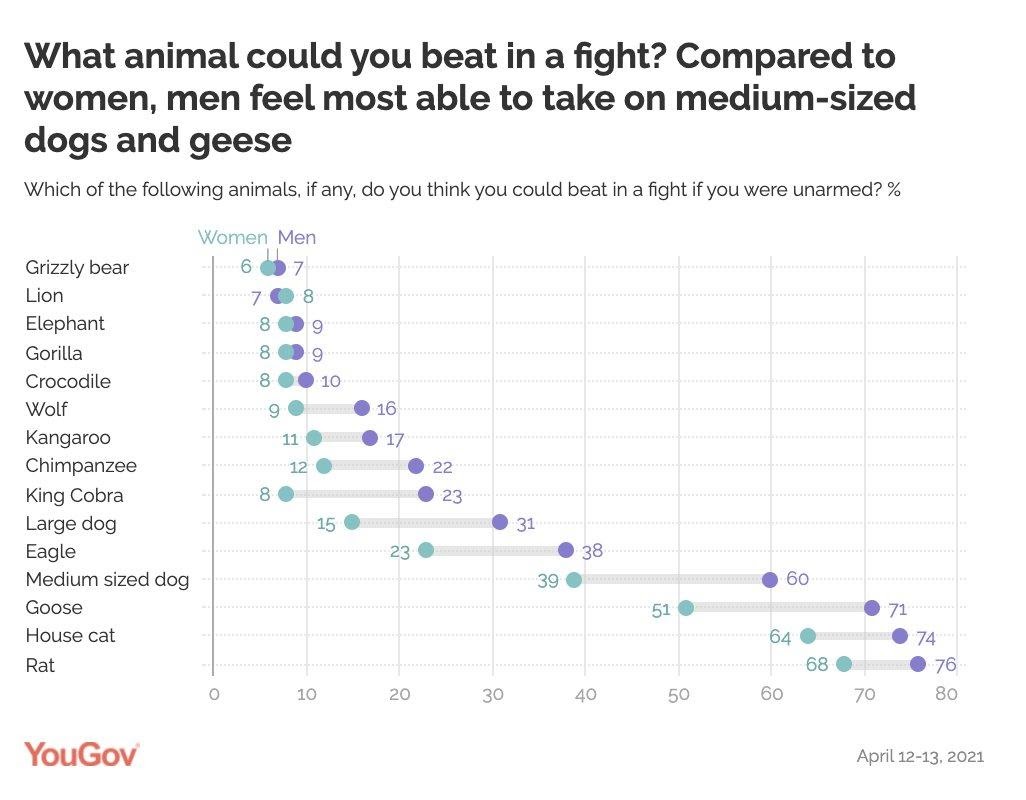

People are weird (source)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.