Dear Capitolisters,

It seems that everywhere you turn these days, people are pessimistic about their (our) economic future. Bloomberg, for example, reports that “everyone is an expert in macroeconomics today, and they’re all predicting a bust of some kind”—part of a boom in economic doomcasting sweeping the media. AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis, meanwhile, sees this Doom Boom (sorry) in a plethora of survey data showing large numbers of American respondents—especially younger ones—worried about the future of the U.S. economy and humanity writ large. And anyone who’s spent more than 10 minutes on social media has seen the laundry list of doomers—on the left and right—confidently predicting all sorts of calamities arising from COVID-19, inflation, global supply chains, China, Russia, or whatever other news cycle bogeyman is peaking at the moment. (No wonder I share so many garden and puppy pics, eh?)

Given the last few years of insanity and uncertainty, some of this pessimism is surely warranted—even I, a shameless optimist and generally sunny dude, have had my moments of doubt, and there are most definitely some gray clouds on today’s economic horizon. On the other hand, the past two-plus years also provide us with a veritable boatload of examples of why—even right now—we should be skeptical of predictions that doom is right around the corner.

Because those predictions keep getting proven utterly—and often ridiculously—wrong.

Pessimism Everywhere—And Not Just During the Pandemic

Over at The Atlantic, Jerusalem Demsas provides several prominent examples of pandemic pessimism and hysteria gone awry:

-

Dire warnings of an “eviction tsunami” of 30 million to 40 million tenants prompted Presidents Trump and Biden, as well as several states, to impose legally and economically dubious moratoria on evictions. These same predictions then pushed numerous housing advocates to warn that the tsunami would emerge once the moratoria were finally lifted. Neither storm, of course, ever materialized. (Demsas kindly cites a recent report showing that “1.36 million eviction cases were prevented in 2021 because of policy interventions such as the eviction moratoriums, emergency rental assistance, and other fiscal support.” Only 30-plus million to go!)

-

The pandemic’s “she-cession,” in which vast numbers of women would drop out of the labor force or scale back their participation, also never happened. In fact, Harvard economist Caudia Goldin finds that “the labor-force participation rate for women ages 25 to 54 was the same in November 2018 as it was in November 2021”; and although this rate is still a smidge below where it was in early 2020, it’s down about the same amount for men too (even more, depending on how you slice it). Thus, Goldin concludes, “the largest differences in pandemic effects on employment are found between education groups rather than between genders within educational groups.”

-

In mid-2020, we also heard widespread tales of a forthcoming state and local budget crisis. (Never mind what my colleague Chris Edwards was saying at the time.) Instead, Demsas reports that “the Government Accountability Office released a report indicating that state revenues had rebounded in the second half of 2020. And although some variation exists in how well states are doing, they’re certainly not facing the crisis once predicted—many states are now even reporting massive surpluses.”

-

Many people also predicted a housing crash in 2020, and … well, we all know how that turned out.

This pandemic pessimism certainly isn’t limited to Demsas’ cases. In August 2020, for example, I wrote on how early 2020 predictions of mass, long-term shortages of hand sanitizer, disinfecting wipes, and other cleaning products—shortages necessitating new government interventions—never came to fruition because supplies materialized “seemingly out of nowhere.” A few months later, I detailed similar adjustments in other critical medical goods sectors:

Many U.S. companies shifted operations to produce high‐demand PPE during the pandemic—an example of the U.S. manufacturing sector’s pre‐existing industrial capacity and flexibility. Others were drawn into the market by sky‐high demand: online crafts retailer Etsy, for example, sold more than $600 million in facemasks during the second and third quarters of 2020 (12 million units in April alone), and “more than 110,000 sellers sold at least one mask between April and June.” Although short‐term gaps in U.S. PPE supply inevitably emerged during the pandemic (due to astronomical demand, pre‐pandemic stockpiling mistakes, or other issues), they were filled in by foreign producers and the stockpiles. As of late summer 2020, for example, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health–approved N95 masks were readily available (for individual or bulk purchase) on websites like Amazon. Several members of Congress even went so far as to write to President Biden complaining about a potential glut of U.S.-made PPE, because the “industry retooled production chains in the spring to respond to the crisis,” and as a result, “domestic production capabilities for essential products like isolation gowns, N95 masks, testing swabs and other critical products have grown exponentially.”

Then, of course, there were the dire predictions in spring 2020 that we wouldn’t have a COVID-19 vaccine for years. Just a few months later, we had two highly effective ones (and others on the way). And who can forget that last year’s supply chain snarls were going to cancel Christmas? Ho, ho… nope.

In case after case after case after case, pessimistic predictions of pandemic peril—cities collapsing (nope); airlines dissolving (nah); bankruptcies exploding (“dust”)—unraveled, as individuals and firms (sometimes, yes, bolstered by government policy) worked to fix near-term problems before they became long-term disasters.

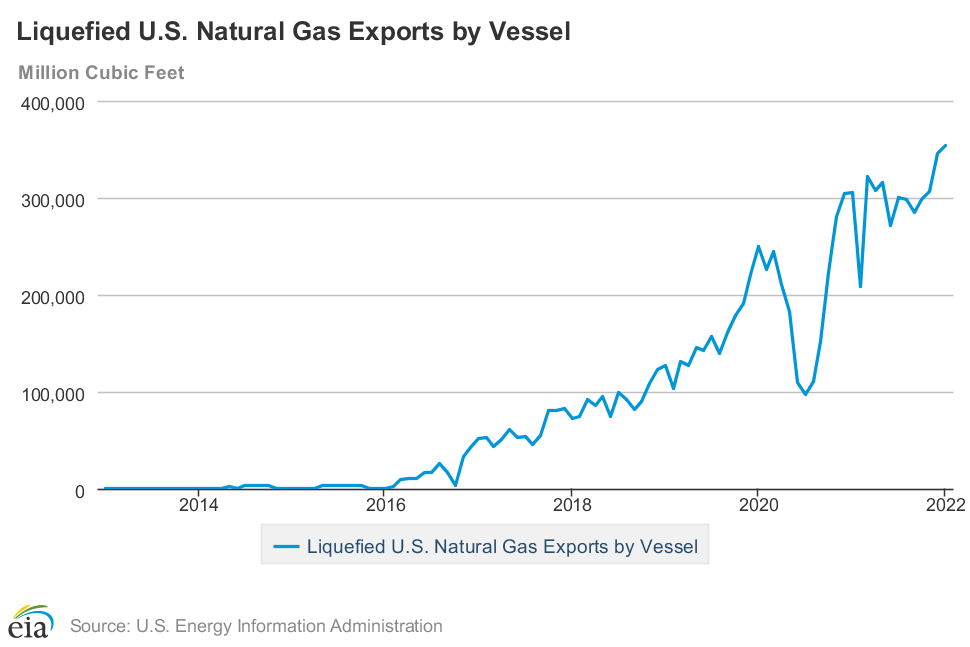

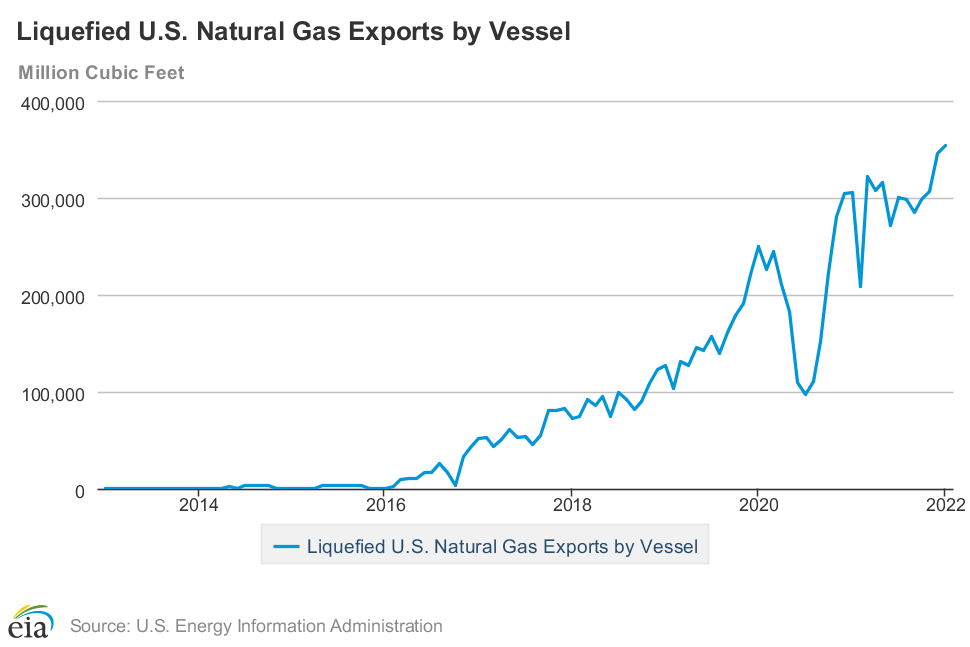

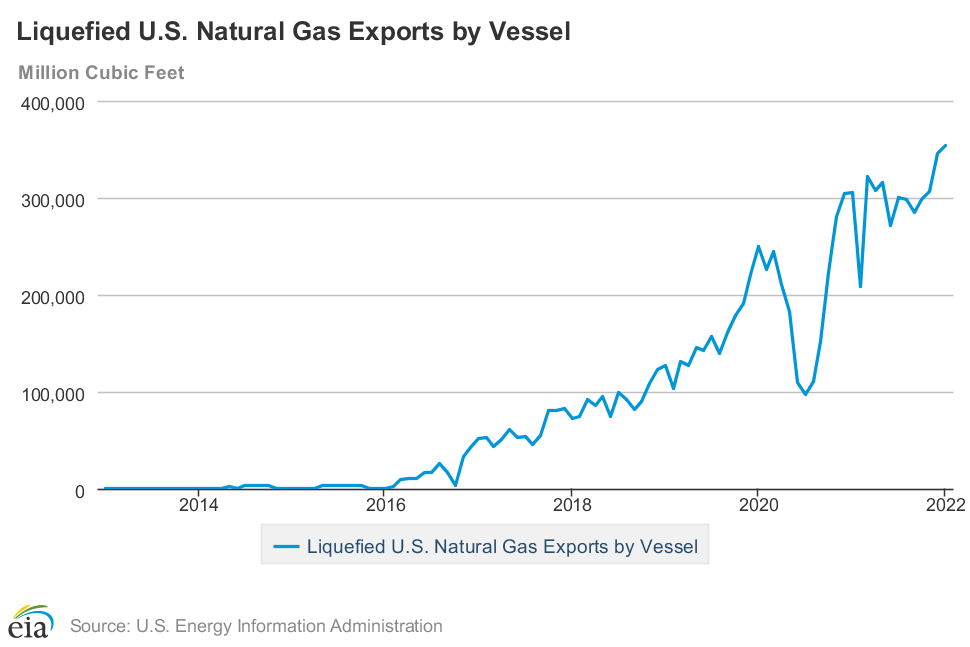

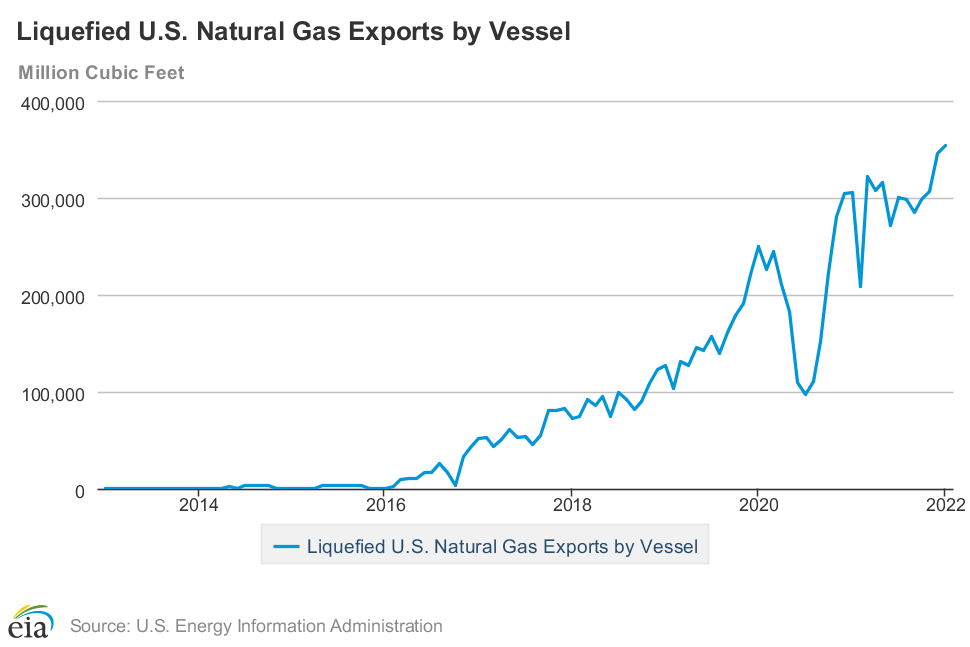

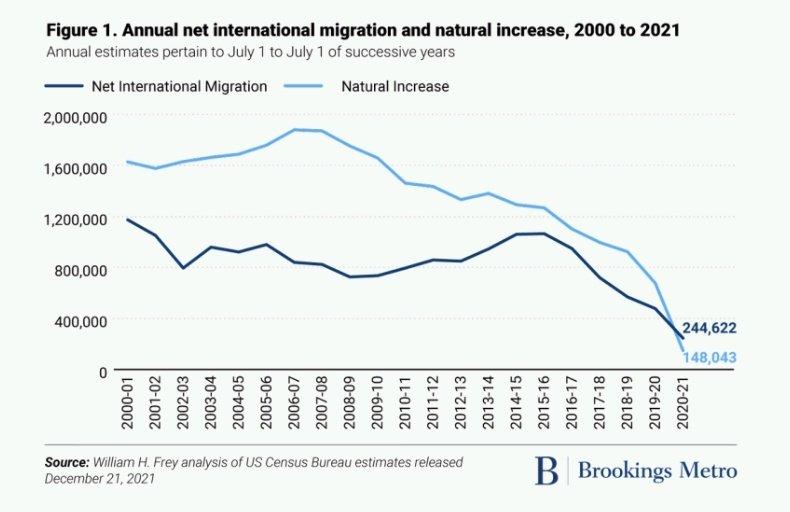

This negativity definitely accelerated during the pandemic, but it surely didn’t start there. As we discussed a couple newsletters ago, for example, people have been wrongly predicting the “Death of Globalization” for years now. (New articles agreeing with my thesis are here, here, and here, if you’re interested.) Years before that, some pessimists claimed that lifting U.S. restrictions on oil and gas exports was unnecessary because—given current market dynamics—the United States would never become an energy exporting powerhouse (and, some added, keeping those restrictions in place was good industrial policy because it would depress the domestic price of oil and gas, which are key industrial inputs). Fast forward a decade, and we’re the world’s top exporter of liquified natural gas (LNG) and a top-five crude oil exporter; 2021 was a “record production year” for U.S. natural gas; and American crude oil and LNG have become an invaluable geopolitical tool in Europe and elsewhere.

A failure to consider economic booms resulting from deregulation is a particular pessimist blind spot. Telemedicine, for example, exploded during the pandemic not because of any new technology but because regulators got out of the way (and, obviously, out of necessity). Years before that, deregulation of state beer and booze markets produced – as we discussed a couple months ago – a craft beer and distillery renaissance that few saw coming. Going back even further, a 1987(!) Cato study recounts how federal bean-counters dramatically underestimated the benefits of trucking reforms:

When trucking deregulation was being considered by Congress in 1980, the Congressional Budget Office forecast that by 1984 the legislation, if enacted, would save consumers $5 billion to $8 billion a year in the prices paid for goods and services. The facts are now available, and the economic benefits produced by partial deregulation are exceeding the Congressional Budget Office’s initial estimates by a factor of 10. Moreover, current calculations of the annual savings enjoyed by U.S. producers and distributors as a result of partial deregulation range from a conservative $56 billion to a high of $90 billion.[Ed note: that’s almost $228 billion today.]

And then, of course, there’s the granddaddy of all dispelled economic pessimism: Malthusianism and the still-kicking “zero population growth” movement. As some readers here surely know, the common mid-20th-century idea that our overpopulated world would run out of resources was put to the test in a famous bet between economist Julian Simon and biologist author Paul Ehrlich, who each had wildly different views on humans and the environment:

In his best-selling 1968 book The Population Bomb, Ehrlich reasoned that over-population would lead to exhaustion of natural resources and mega-famines. “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate,” he wrote.

Simon, in contrast, was much more optimistic. In his 1981 book The Ultimate Resource, Simon used empirical data to show that humanity has always gotten around the problem of scarcity by increasing the supply of natural resources or developing substitutes for overused resources. Human ingenuity, he argued, was “the ultimate resource” that would make all other resources more plentiful….

In October 1980, Ehrlich and Simon drew up a futures contract obligating Simon to sell Ehrlich the same quantities that could be purchased for $1,000 of five metals (copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten) ten years later at inflation-adjusted 1980 prices. If the combined prices rose above $1,000, Simon would pay the difference. If they fell below $1,000, Ehrlich would pay Simon the difference. Ehrlich mailed Simon a check for $576.07 in October 1990. … The price of the basket of metals chosen by Ehrlich and his cohorts had fallen by more than 50 percent.

As my Cato colleague Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley wrote a few years ago, Simon’s optimism remains warranted today:

[A Cato study] looked at population, prices, and income from 1960 to 2016. Over these 56 years, world population increased by 145 percent, from 3 billion to almost 7.5 billion. Yet, inflation-adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) per person increased by 183 percent, from $3,689 to $10,391. So, income grew 26 percent faster than population—just as Simon had predicted…. The study looked at prices of 42 natural resources from 1960 to 2016, as tracked by the World Bank. Adjusted for inflation, 19 declined in price, while 23 increased in price. Out of those 23 commodities, only three (crude oil, gold, and silver) appreciated more than GDP per person.…. The overall inflation-adjusted price index of the 42 commodities increased by 33 percent over the 56-year period. However, after adjusting for the appreciation in GDP per person, commodity prices fell by 53 percent. Humanity is creating faster than it is consuming. That is an astonishing verification of Simon’s prophecy.

You’d think that, after all these years of humans successfully adapting their way out of crisis (see Pethokoukis’ piece or Tupy’s new book for more), the pandemic would’ve featured just a smidge more optimism—or, at the very least, more wait-and-seeism. Yet the pessimism thrived.

Why So Pessimistic?

Demsas suggests four reasons for why so many people have lapsed into misguided gloom since 2020, but it’s the last two that, I think, provide lessons for economic doomerism beyond the pandemic. First, she notes that most of the hysteria (that she cited, at least) came from advocacy groups pushing government programs that they’ve long embraced:

Many early pandemic predictions pointed toward a similar solution: a left-of-center policy agenda. A she-cession justified universal day care and paid family leave; an eviction tsunami justified stronger legal protections for renters; state and local distress seemed to require what Republicans called “blue-state bailouts.”…

I don’t mean to suggest anything more sinister than motivated reasoning. Some advocates may have regarded the coronavirus pandemic as an opportunity to shoehorn in important social policies that they felt were long-justified, and, to a certain extent, they saw in the data what they wanted to see. As Hepburn, the sociologist, argued, the [eviction] numbers generated by Aspen may have been useful “from a lobbying standpoint,” and Panfil noted that perhaps “it was helpful to the movement of activists who were pushing for relief measures to be put into place to cite some of these larger figures.”

Similar things can be said, I think, about endless “supply chain” doomerism coming from economic nationalists, or when anti-Wall Street populists warned that hedge funds were buying all of our houses (still nope), or when “Main Street” small business organizations argued for new antitrust actions because the pandemic made “Big Tech” e-commerce unstoppable (see the first Chart of the Week below). All too often, you scratch economic hysteria and you find policy-driven confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, or just plain ol’ rent-seeking underneath.

Second, Demsas argues that folks simply underestimated their fellow humans’ ability to adapt and survive, if not thrive, during the pandemic’s admittedly-tough times (emphasis mine):

Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, marveled at “the resilience, creativity, and ingenuity of people and businesses and workers” when we spoke. He told me that “businesses really figured out a way to survive. That meant that as the economy returned to normal, there were businesses around to hire unemployed workers.” And although many small businesses closed, others opened; in fact, more small businesses exist now than did before the pandemic.

Essentially, when things get bad, most people figure it out. They find a way to make rent, to stay in business, to work a full-time job even as they care for children or sick relatives. Many forecasters seem to have underestimated this resilience.

As this kind of “resilience” is a common theme of my writing, I’m of course nodding in agreement. But I also think this issue is related to the first: people—on the left and (increasingly) the right—who strenuously advocate for government action rarely seem to consider that the inevitable “market failure” they see today might not be so inevitable tomorrow, that millions of individuals in relatively free markets will adjust pretty quickly in mutually beneficial ways, and that, in so doing, those people might not only muddle through but often improve things in ways we couldn’t have previously imagined. The pessimistic “planners,” armed with policies designed to fix yesterday’s crisis, can’t seem (or don’t want) to comprehend that, far more often than not, markets and individuals will eventually, albeit messily, figure their ish out. (Hence, the urgent “need” for all those big plans.)

On the other side of the coin, there are those of us who think that, when people are free to pursue their own interests, they’re pretty darn good at working with others to survive and innovate in times of crisis. We’re also keenly aware of the things we don’t and can’t possibly know—Hayek’s “Knowledge Problem” and all that—and how government intervention might thwart voluntary cooperation and adjustment. On this last point (and relevant today), for example, I noted way back in the first Capitolism newsletter that, with eviction moratoria in place, we could see “tenants and landlords discouraged from coming to a voluntary, private agreement on modifying the lease at issue” (sigh).

Overall, we “free market optimists” are far more inclined to believe that the economic catastrophes on the horizon probably won’t be there when our car finally gets down the road—assuming the pessimistic planners get out of the way. As Tupy and Pooley put it about The Ultimate Resource:

In the book, Simon dismissed the widely held belief that population growth must inevitably result in poverty and famine. Unlike other animals, he argued, humans innovate their way out of scarcity by increasing the supply of natural resources or developing substitutes for overused resources. Human ingenuity, in other words, is “the ultimate resource” that makes all other resources more plentiful.

Simon got it right back then, and anti-doomerism (mostly) prevailed again during the pandemic. Sure, things got rough at times (it’s a global pandemic!); unexpected problems arose (hello, Delta); and messes remain. Overall, however, human ingenuity prevailed, and I’d wager it will again. Call it faith, call it optimism, call it whatever you want—as long as you also call it backed by decades and decades of reality.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.