Happy Tuesday! Effective immediately, we here at TMD are now ignoring any and all feedback that doesn’t come from “big Egger, Isgur, and Garvey fans.”

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

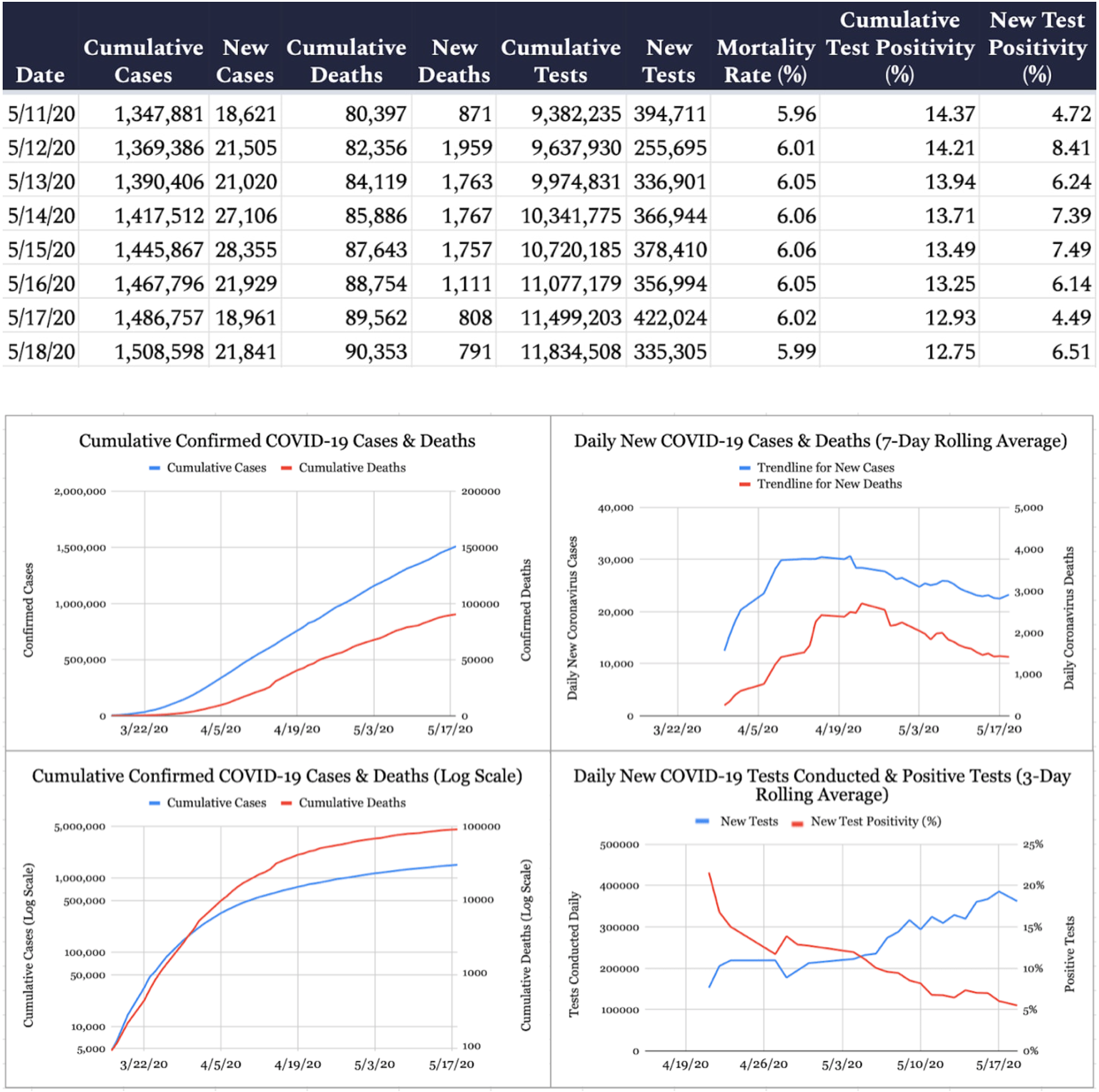

As of Monday night, 1,508,598 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States (an increase of 21,841 from yesterday) and 90,353 deaths have been attributed to the virus (an increase of 791 from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 6 percent (the true mortality rate is likely lower, but it’s impossible to determine precisely due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 11,834,508 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States (335,305 conducted since yesterday), 12.8 percent have come back positive.

-

Markets soared on Monday after the drug maker Moderna announced an early trial for a potential COVID-19 vaccine showed patients had developed neutralizing antibodies to the virus. The Phase I trial was led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and featured only a small number of participants, but experts see the results as encouraging. China has promising coronavirus vaccines in development as well, four of which are already in human trials. President Xi Jinping spoke to the World Health Assembly Monday and promised any resulting vaccine “will be made a global public good.”

-

President Trump sent a letter to World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warning him if the WHO doesn’t “commit to major substantive improvements within the next 30 days,” the United States will make its temporary funding freeze of the organization permanent and “reconsider” its membership.

-

In comments that threw some cold water on President Trump’s recent “Obamagate” missives, Attorney General Bill Barr told reporters Monday that he does not expect an investigation into the origins of the Russia inquiry to implicate Barack Obama or Joe Biden. “As long as I’m attorney general, the criminal justice system will not be used for partisan political ends,” he added.

-

The FBI uncovered evidence linking Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani—the gunman who shot and killed three servicemembers at a Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida last December—to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. The bureau was able to gain access to Alshamrani’s iPhone despite “effectively no help from Apple,” according to Director Christopher Wray. Apple has, since 2014, refused to create a “backdoor” into its products for law enforcement officials, citing privacy rights.

-

President Trump’s firing of State Department Inspector General Steve Linick came into sharper focus on Monday, with the president telling reporters that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo asked him to relieve Linick—appointed by President Obama—of his duties. Pompeo told the Washington Post that Linick—who was in the process of investigating both American weapons sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and Pompeo’s alleged tasking government employees with his personal errands—was “undermining” the department’s mission.

-

President Trump told reporters he began taking hydroxychloroquine over a week ago—after several White House aides tested positive for COVID-19—for what he claims is its prophylactic effect. Despite a series of studies failing to find evidence the anti-malaria drug prevents or cures COVID-19—and some finding significant side effects including increased risk of death—Dr. Sean Conley, Trump’s physician, said he and the president “concluded the potential benefit from [hydroxychloroquine] outweighed the relative risks.”

-

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced Sen. Marco Rubio will temporarily replace Sen. Richard Burr as chairman of the upper chamber’s Intelligence Committee while Burr is investigated for suspicious stock trades.

Creeping Forward on Vaccines

Make a list of the worst things about our current pandemic predicament, and the top two items are obvious: The death and suffering brought about by the disease, and the toll on the economic well-being of people in our country and around the world. The third spot would likely go to our sense of stagnation—the feeling that, although the pandemic is an ongoing peril that continues to disrupt our lives, nothing is happening with it. Some places are beginning to reopen, sure, but the basic story of the virus seems to remain the same day after day. Actually defeating the disease and getting back to normal still feels like an abstraction, one which isn’t getting closer in any obvious way.

But the reality is just the opposite: While a workable vaccine is still a long way off, the world’s scientists are currently moving in that direction very quickly. Yesterday, biotech company Moderna announced that its nascent vaccine has created promising levels of antibodies in patients in preliminary testing. The news lifted markets and was widely cheered by public health experts, such as former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb:

It’s important to stress that these results are still very preliminary. It’s one thing to know that a vaccine can produce the desired immune response in some people, but a plethora of questions have yet to be answered.

What dosage is necessary to achieve the desired response? Finding the minimum effective dose is important: “Overdosing” on a vaccine won’t typically lead to negative health outcomes, but a smaller dose means a given quantity of the vaccine can be spread among more patients. It will likely be a long time before the supply of the first working coronavirus vaccine is sufficient to meet our demand for it.

Will there be side effects? When it comes to therapeutics, doctors treating COVID patients have been throwing everything at the problem, trying different medicines in the hope of finding anything that will help their patients.

“We sort of hold to a lesser standard drugs,” Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and virologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told The Dispatch last month. “When you’re sick, you’re willing to tolerate side effects you’re not willing to tolerate when you give something to somebody who’s perfectly well.”

Will it work for everybody? Just because a vaccine can create necessary antibodies to immunize a person from a disease doesn’t mean it will provoke that same reaction in everyone. Dr. Wayne Koff, the president and CEO of the Human Vaccines Project, told us that one central challenge for COVID researchers is that the elderly are less likely in general to build up antibody protection from a vaccine—a major hurdle, given they’re the ones with the most to fear from the virus in the first place.

Finding answers to all these questions will require rounds of clinical trials, which will take time, and there’s no guarantee Moderna’s vaccine—or any other company’s—will manage to run the gauntlet successfully. But it’s good news that at least one vaccine is already ready to embark on that stage.

This also means that another ethical debate about the process is about to get a lot more urgent: the possibility of using what are called human challenge trials to speed up the process. One of the most time-consuming periods of a vaccine’s development it its phase III efficacy trial: a huge, placebo-controlled test of the vaccine’s effectiveness administered to a slice of the general public in areas where disease transmission is occurring. The trial has to be big enough and long enough to account for a lot of noise in the data, because there’s no way of knowing who will be exposed to the virus in advance.

There’s a simple way around that problem: Just perform the study on young, healthy subjects who consent to be infected with the coronavirus directly. This would dramatically speed up the trial and, thus, potentially allow a lifesaving vaccine to hit the shelves weeks or even months sooner than it otherwise would. But it’s sticky situation ethically that risks running afoul of the “do no harm” precept of the Hippocratic Oath, particularly considering that the effects of the virus are not yet fully understood: Just because a group is “low-risk” in theory doesn’t mean we can project with confidence that none of its members will become critically sick or die.

That hasn’t stopped a number of scientists from arguing that the U.S. should proceed with such trials. Dr Stanley Plotkin, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, has been arguing for weeks that the benefits of human challenge trials far outweigh the drawbacks in a race to cure a global pandemic.

“Historically, challenge studies have been approved and carried out even with the risk of death,” he wrote in a recent article for the Human Vaccines Project. “If great care is taken to ensure the informed consent of volunteers, correct participant selection and trial procedures, and the competency of research teams, challenge studies should achieve approval by sponsors and research review committees.”

At this moment, we’re still a long way away from Phase III tests of any kind for any drug. But as we creep closer, look for these debates to become a central part of our coronavirus discourse.

Worth Your Time

-

“Despite the challenging circumstances, and the dire headlines we read, there is still reason for hope in our country,” former first lady Laura Bush writes in a brief essay shining a light on just a few of the millions of helpers in the COVID-19 pandemic. “All around us, there are helpers. Some of them look like those we’ve recognized as heroes before — doctors, nurses, firefighters and police officers. But we found that heroes can also be teachers, store managers sewing masks to fit children, principals who organize community car parades to show students they are still loved, or even a neighbor who picks up groceries so a mom can stay healthy at home with her newborn baby. Now is a great time to teach our children that everyone can be a hero.”

-

Joe Biden is losing the internet to President Trump, whose re-election campaign has millions of dollars and countless meme-smiths working on behalf of its digital operation. But according to veteran campaign reporter Peter Hamby, it might not matter. “Biden will lose in November if he chases virality and follower counts that don’t actually grow support among voters, and he’ll lose if he tries to Xerox another candidate’s playbook,” he writes for Vanity Fair. “Biden can win if he understands that he doesn’t need to ‘win the internet’ to win the White House—and that Trump is actually losing in the polls despite being an omnipresent force online.”

Something Sweaty

One of your Morning Dispatchers (who will remain nameless) finally decided that 10 weeks of next-to-no exercise was probably not great for either physical or mental health. These daily videos from fitness coach Joe Wicks—streamed for free on YouTube and requiring no equipment—have started to kick things back into shape.

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Also Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

The aptly titled “Ultimate Supreme Court Nerdery Part I” episode of Advisory Opinions features David and Sarah previewing a number of upcoming Supreme Court decisions, plus a discussion of Rep. Justin Amash’s short-lived presidential campaign, and Ben Smith’s latest New York Times column scrutinizing Ronan Farrow’s journalistic ethics.

-

The House on Friday passed its $3 trillion HEROES Act extending many CARES Act economic relief measures and introducing a laundry-list of otherwise unrelated Democratic priorities. Senate Republicans have made clear the legislation is dead on arrival, but in a piece for the site, Abby McCloskey argues the GOP should be crafting alternative legislation rather than just blasting the Democrats’ bill. “There’s understandably growing exhaustion among fiscal conservatives about the level of government spending in the coronavirus response, but the costs are likely to grow further if the current economic sclerosis continues,” she writes. “Give Americans a path forward that instills confidence, security, and hope. Put meat on it. Let people know you are in it with them for the long haul. Republican politicians tend to do poorly on surveys about whether they ‘care about people like me.’ Now’s the time to push against the caricature with compassion and urgency and targeted support.”

Let Us Know

When a COVID-19 vaccine does come, what’s the first thing you’ll do post-inoculation?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph of scientist Xinhua Yan in the lab at Moderna in Cambridge, Massachussetts, by David L. Ryan/Boston Globe/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.