Will ‘Human Infrastructure’ Overheat the Economy?

Good afternoon and Happy Friday. Let’s get to the news.

You Get a Trillion! And You Get a Trillion!

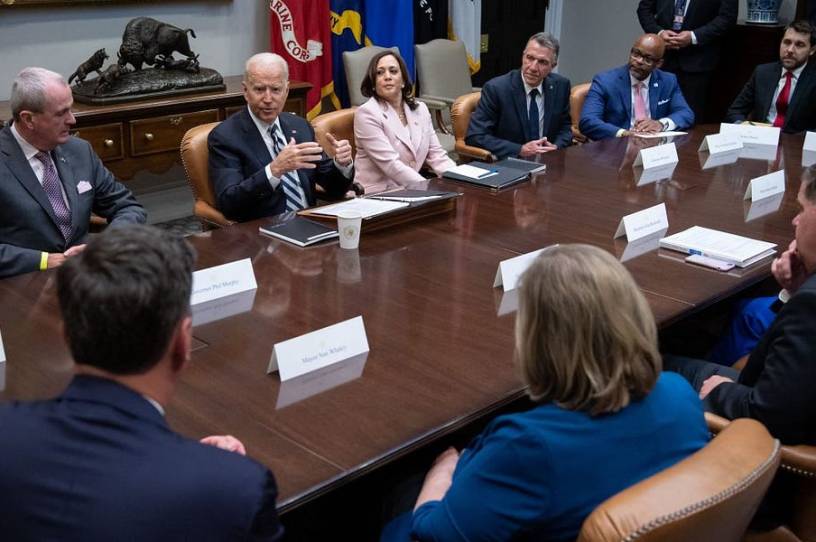

On Tuesday, Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee reached a breakthrough on a $3.5 trillion proposal to address President Joe Biden’s agenda on health care, education, climate, and poverty programs. Biden ventured to Capitol Hill Wednesday to sell the plan to Senate Democrats.

Democrats and the White House see this package as a complement to the narrower, almost $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure deal a coalition of moderate lawmakers struck recently to shore up the nation’s roads, bridges, airports, and broadband internet.

If both are passed—and at this point that remains a big if—the price tag would represent an astronomical amount of federal spending, as Republicans have been quick to point out. It also comes on the heels of $4 trillion of COVID-19 relief and stimulus enacted under both Biden and at the tail end of the Trump administration.

The price tag has raised the question: Will increased government spending, at such a massive scale, contribute to an overheating economy? The most recent U.S. government’s report on inflation, which showed another rise in prices, added both fuel to such concerns and another layer of uncertainty to the outlook of these spending packages.

Consumer prices have jumped 5 percent over the last year. As The Morning Dispatch covered Wednesday:

The CPI increased 0.9 percent from May to June according to this month’s BLS report, and 5.4 percent year-over-year. Both data points exceeded economists’ expectations yet again (0.5 percent and 4.9 percent, respectively), and both represent the fastest price growth in 13 years.

There are some caveats worth keeping in mind when looking at these eye-popping figures. Although the influence of the year-over-year base effect is beginning to wane—most states had eased the harshest of [COVID-19] lockdown restrictions by June 2020—current prices are still being measured against a fairly low starting point. Remove that, and things don’t look quite as dire. The CPI has risen 5.4 percent over the past year, but a much more manageable—though still higher than normal—3 percent averaged over the past two years.

Part of the spike is also attributable to the aches and pains of the economy lurching back into full motion, as Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell argued in testimony before the Senate Banking Committee this week.

“This is a shock going through the system associated with reopening of the economy, and it has driven inflation well above 2 percent,” he said. “To the extent [inflation] is temporary, it wouldn’t be appropriate to react to it.”

Mitigating factors aside, public support for more government spending might wane if inflation keeps climbing. As TMD noted, a mid-June survey found 71 percent of U.S. voters believe inflation is a “very big” or “moderately big” problem. Sixty-five percent of respondents think increased government spending has contributed to the phenomenon.

On top of that, the federal budget deficit continues to grow. At current levels of spending—not counting any of the plans currently under discussion—the federal government is already $2.2 trillion in the hole in FY 2021 alone, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Predictions of whether more federal spending will drag down a recovering economy and keep prices high for Americans split mostly along partisan lines on the Hill. Economists, too, are divided. But many prognosticators are sunnier than one might expect from practitioners of the dismal science: Some argue that the plan’s design means there is less need for concern about immediate inflation than in other big-spending bills.

“Most of the money starts a year or two in the future, and it will be to some degree paid for, although the magnitude of the pay-fors and the reality of the pay-fors are obviously [to be determined],” Jason Furman, a Harvard economic policy professor, told The Dispatch.

That’s in contrast to stimulus bills like this year’s American Rescue Plan, “where about $2 trillion dollars went into the economy in a single year, a lot of it within a week or so of passing,” Furman said. “That’s impossible for the [Federal Reserve] to deal with.”

But the current proposal, Furman said, “is much more about the economy over the next five, 10, 15 years than it is about combating the recession.”

Senate Democrats are running with a similar argument.

Sen. Bob Casey, a member of the Senate Finance Committee, told The Dispatch Wednesday that the $3.5 trillion proposal, if passed, would be distributed gradually over the next decade: “I think that that has a mitigating impact on that kind of inflationary concern.”

“This isn’t like the [American Rescue Plan], where a great deal of money went into the economy in a matter of months,” Sen. Angus King, independent from Maine, told The Dispatch. “These are long-term projects, some of which will probably be five to seven years in the building.”

Of course, no one has seen the actual text of either the bipartisan infrastructure package or the budget reconciliation proposal, dubbed by Democrats the “human infrastructure” package, nor has the Congressional Budget Office scored them. It is still unknown whether the CBO will count the packages as fully “paid for.”

Furman said he sees inflation as more of an issue for the Fed to deal with, not Congress. “Anything in the future that the Fed wants to offset it can by raising interest rates. And even if they go up they will still be low.”

But others expressed more skepticism.

“That’s a lot of ifs and hopes and dreams,” William McBride, a tax policy expert at the nonpartisan Tax Foundation, told The Dispatch. “If those senators can predict where the economy will be in two years when that spending will be fully entering the economy—then wow, more power to them. But I don’t think they can actually predict with any accuracy where the economy will be in two years.”

“It remains to be seen if this is a temporary episode or not,” McBride said. “If monthly measures are continuing to be high this fall, I would say that’s a cause for concern. I think they [should] certainly reconsider the spending.”

As TMD covered today, while the specific policies that will make it into the bill are still under construction (pun intended), it is chock full of Democratic priorities: universal prekindergarten, two years of free community college, an expansion of the child tax credit, incentives for clean energy, a paid family leave and medical leave program, and more. It would also expand Medicare to provide dental, vision, and hearing benefits.

Democrats see another opportunity in these groups of bills: immigration reform. Currently, they hope to include a pathway to citizenship for DACA recipients—otherwise known as “dreamers”—in the budget reconciliation package. That plan faces one big hurdle, however: It will be up to the Senate parliamentarian to decide if immigration falls within the purview of the budget reconciliation process.

The proposal is expected to include a host of tax hikes, primarily on corporations and wealthy Americans. Democrats have said the full cost of the bill will be paid for, but the details have yet to be hashed out.

Republicans, meanwhile, are sounding alarms.

“There’s already so much money sloshing around from the previous appropriations that I think you have a lot of money that’s chasing limited goods and services, and it’s bidding up the prices,” Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican and member of GOP leadership, told The Dispatch. “So I think this would make things worse when it comes to inflation.”

Cornyn added that he had talked to Powell about his concerns: “Well, he said he thinks it’s transitory. And I don’t know. You know, I guess it’s gonna be transitory until it’s not anymore.”

Progressive Democrats brushed aside inflation concerns almost entirely.

When asked if she was concerned that the size of the spending may contribute to inflation, Sen. Elizabeth Warren simply responded, “No.”

“[If] we want people to be able to start small businesses, then we need roads and bridges so they can get their goods to market,” she added. “This is how we build a bigger GDP and make ourselves a wealthier nation.”

“Obviously, we want to keep inflation as low as possible,” said Sen. Bernie Sanders, who chairs the Senate Budget Committee. “But it’s absolutely imperative that we address the needs of working families, and that we pay for these programs by demanding that a One Percent, who have seen an explosion in their incomes and wealth, start paying their fair share of taxes.”

With a 50/50 split in the Senate, no bill is ever guaranteed to pass even with a bipartisan group of senators working together. However, 11 Republicans and 11 Democrats have endorsed the smaller bipartisan deal. The details, specifically how to pay for everything, are still being ironed out and have hit some snags. Most notably, Republicans are concerned about a provision that would give the IRS more tax enforcement power.

“We’ve got a long way to go. Pay-fors are still a big part of this that we really don’t have resolved yet,” Sen. Mike Rounds, one of the 11 Republicans to agree to the bipartisan bill, said on Thursday.

Meanwhile, Democrats want to pass their partisan plan through a process known as budget reconciliation, which allows them to circumvent the 60 votes needed to advance legislation and rely on a simple majority instead. Democrats used reconciliation in March to pass the American Rescue Plan, and the GOP used reconciliation to pass the Trump-era Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017.

Items passed via reconciliation will face scrutiny from the Senate parliamentarian, and must adhere to strict guidelines regarding budgetary impacts. The parliamentarian recently ruled that a provision to increase the minimum wage to $15 an hour fell outside the boundaries of reconciliation.

On Thursday, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer announced senators will have until Wednesday of next week to come up with a final plan for both the bipartisan infrastructure bill and the budget reconciliation package, bringing both plans to the floor of the Senate for consideration.

“The time has come to make progress,” Schumer said on the floor. “And we will. We must.”

Presented Without Comment

Something Fun

Of Note

Congressman and dentist Paul Gosar is giving the American Dental Association a ‘toothache’

As the Use of AI Spreads, Congress Looks to Rein It In

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy deems misinformation a threat to “public health”

Senate will vote on military justice shakeup this year, Gillibrand says

We hope you are enjoying Uphill. To ensure that you receive future editions in your inbox, opt-in on your account page.