How Madison Lost Control of Its Protests

On the night of Monday, June 8, a small group of protesters began to congregate outside the city and county administration building in Madison, Wisconsin. The young demonstrators began hauling out yellow paint and adorning Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard with the words DEFUND POLICE, as large as the street is wide.

This particular demonstration was more than a bit ironic, as the police presence was virtually nonexistent as the protesters vandalized the street, which leads to the State Capitol just a block away. A spokesman for the Madison Police Department told me there were officers on the scene, although “visible police presence was at a distance.”

With the police monitoring from afar, teenage boys served as law enforcement, directing traffic and telling reporters where they were allowed to take photos of the street.

Those protests marked the 10th day of demonstrations in Madison, a city that is to protesting what Philadelphia is to cheesesteaks or Seattle is to precipitation. Nearly a decade ago, the city made national news as hundreds of thousands of protesters filled its streets and occupied the State Capitol to protect the viability of public sector unions.

In recent years, however, the overwhelmingly white, disproportionately high-income, and nearly universally progressive city has struggled to adapt to its changing racial demographics, often with disastrous results. Even though the city itself is only 7 percent African American, protests in Madison inspired by the police-instigated death of George Floyd have rattled the medium-sized Midwestern city.

But the city’s response to the protests has been a warning to other cities tempted to appease activists by reducing their policing. For years, Madison has capitulated to a vocal cadre of young instigators complaining about disproportionate treatment of the city’s growing black population.

And the city’s handling of the George Floyd protests would be no different.

Given that the protests were objecting to excessive policing tactics, Madison Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway decided that interactions between police and protesters should be kept to a minimum. Consequently, at 8 p.m. on the first night of the protests, Rhodes-Conway announced that police would not be making arrests, virtually handing the most aggressive demonstrators a license to smash windows and loot local businesses.

“I share the demonstrators’ passion, frustration and resolve that serious social change is needed in our nation,” Rhodes-Conway said.

(Rhodes-Conway, a 49-year-old white Smith College alumna, was elected in April 2019 because incumbent Mayor Paul Soglin, a 1960s era radical who once gave a key to the city to Fidel Castro, was considered by many in Madison’s universally progressive downtown areas to be too conservative.)

Predictably, after many of the peaceful protesters went home, COVID-19 masked rioters gained control of the city. State Street, which connects the Capitol to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, saw dozens of businesses either looted or heavily damaged. When police did show up to restore order, they were pelted with rocks and water bottles.

Angel Smith, a 25-year-old woman who is also nine months pregnant, told the local newspaper that she proudly helped push a line of police back about a block and a half before she was maced.

“When my daughter grows up, I want her to speak up and speak out and learn not to be afraid,” she told the Wisconsin State Journal.

One block off State Street, an unattended police car was broken into and two long rifles and ammunition were stolen. The car was then set on fire, and a young man hopped in the car and drove it less than a block away, where it exploded into flames. He was not hurt.

At 11:30 p.m. Rhodes-Conway declared a state of emergency and implemented a curfew. Working from the standard riot playbook, she blamed outside agitators for the violence, saying, “We don’t want you here, and we reject any attempt to incite violence.”

Yet the nights that followed also saw widespread violence and vandalism. With mixed levels of police presence, graffiti was spray-painted on the state veterans’ museum, bronze statues outside the Capitol were doused with paint, and a large expletive was sprayed on the Capitol itself. A reporter on the scene told me the picturesque Capitol square looked like a “war zone.”

A spokesperson for Madison police told me that officers weren’t deployed in “soft uniforms” because the previous day, a group of officers had been physically confronted. Instead, the demonstrations “were monitored from a distance” and mobile response teams were deployed in vehicles with access to protective gear “to allow for a quicker police response to criminal activity.”

But the hands-off policing strategy wasn’t enough to save the businesses along State Street, as virtually every storefront was hit by graffiti, broken windows, or looting. Some businesses suffered hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages; a poll by a downtown business group indicated that, between losses from the pandemic and the protests, 40 of the 100 businesses surveyed had no intention of reopening. The county Boys and Girls club began hiring neon-yellow vest-wearing “peacekeepers” at $12.83 an hour to protect businesses from looters.

Nonetheless, while Rhodes-Conway condemned the property damage, she continued to express sympathy for the protesters.

“If you are angry because you want those who broke windows and trashed sidewalk cafes … to face consequences, be more angry that the people who kill black people all too often walk free,” she said at a press conference after the first night of rioting.

Over the next few days, Rhodes-Conway, trying to put a positive spin on the damage, tweeted pictures of the murals that artists had begun to paint on boarded up State Street windows.

“Thank you local artists for your great work on State Street this week,” she wrote, neglecting to acknowledge the lost income, jobs, and merchandise that lay behind the boards.

“You are brightening our days!,” she wrote.

Later, she joined protesters from activist groups known as Freedom Inc. and Urban Triage on a march blocking John Nolen Drive, a major artery into the city. With the road blocked, a dance party broke out, with protesters—largely high-school aged African American girls—taking part in the “Cha Cha Slide.”

The protest blocked the street for eight hours.

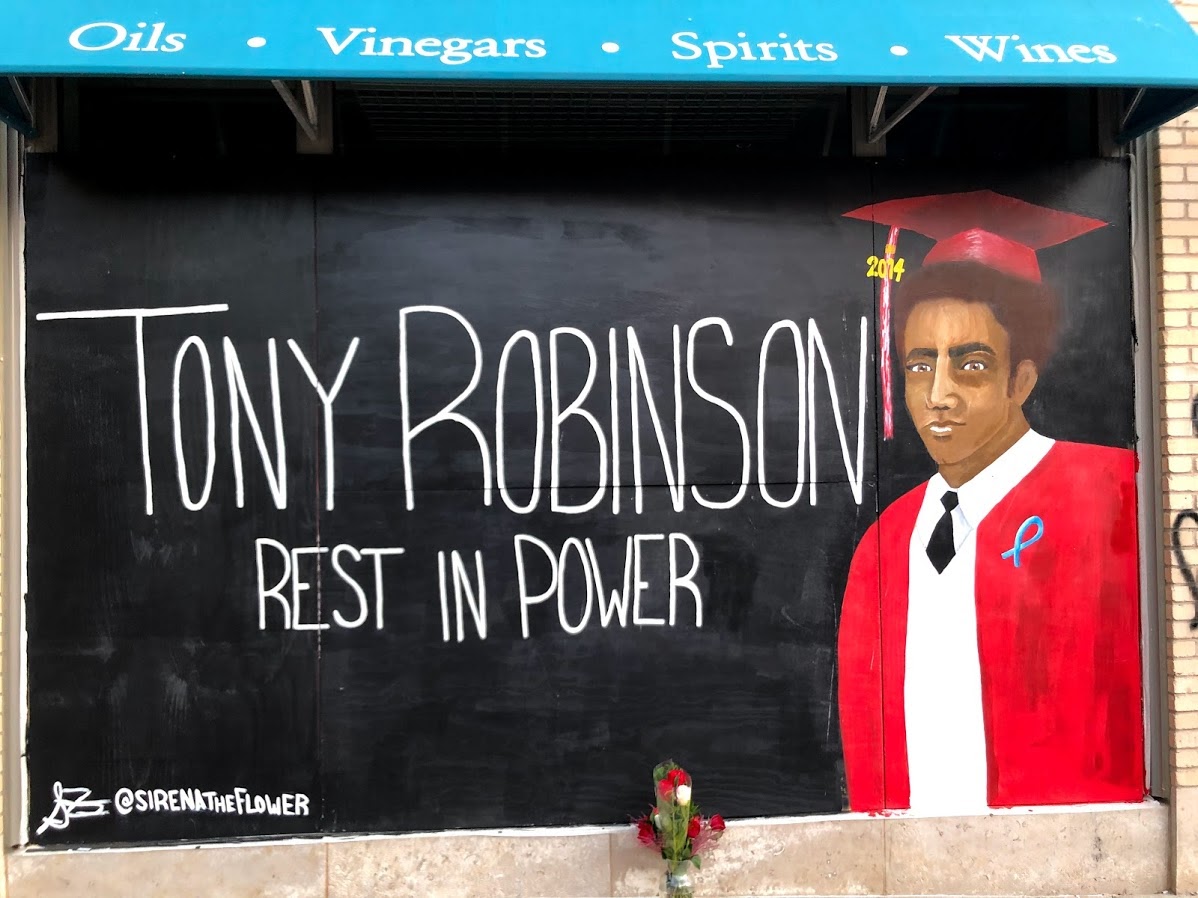

The cause célèbre of the Madison protesters has been the 2015 shooting of a 19-year old biracial man named Tony Robinson, who, on the night of the incident, had been on marijuana, hallucinogenic mushrooms, and Xanax. Officer Matt Kenny, who was dispatched to the scene in response to several calls complaining about Robinson’s behavior, said the young man met him in a stairwell with a punch to the face. According to Kenny, the two fought, and Kenny said he shot Robinson because he was fearful of what would happen if Robinson got a hold of his gun.

In May 2015, Dane County District Attorney Ismael Ozanne, himself African-American, gave an emotional press conference in which he announced he would not be pressing charges. Kenny is still on the police force.

It is largely this incident that led Freedom Inc. to demand the complete defunding of police in the city. As newspapers across the nation parsed exactly what “defund police” meant—in some areas, it could be read as “reform police” or “divert funds from police departments to mental health and other social services”—the Madison protesters’s demands were perfectly clear. Freedom Inc. called for police to be “abolished,” especially in “neighborhoods where people of color are concentrated.”

Ironically, if the police force were defunded, taxpayers would still be funding Freedom, Inc. In the past five years, the group has received $3.6 million in state and federal grants for “minority and LGBTQ advocacy.”

Madison’s troubling capitulation to social justice groups hasn’t just been in city government. In 2014, the city school district, recognizing that its suspension policy inordinately affected African-American children, effectively did away with suspensions altogether.

While the district called the plan “a progressive and restorative approach to behavior and discipline,” the kids recognized it as something different completely—they now had the run of the schools, knowing there were no punishments for bad behavior.

“What’s changed is kids have the mindset that they are in charge now,” said one teacher to a local newspaper. “You walk into the school and there are just kids everywhere. Walking the halls. Leaving the classrooms whenever they want,” she said.

“If a kid says, ‘F— you’ to you six or seven times and there are no repercussions—it becomes pretty clear who is in charge,” said another teacher.

The school district, along with the city, has been caught completely flat-footed by the area’s new racial diversity.

The black population of Madison has doubled since 1990; in 1991, Madison public high schools were 81 percent white; by 2018, that number had dropped to 44.7 percent. During that time, the number of black high school students nearly doubled, while the number of Hispanic and Latino students has grown from 160 to over 1,500.

This demographic shift has given ammunition to racial justice groups that claim Madison, perhaps the most proudly progressive city in America, is also one of the worst for black people in the country. Much of this is because the city has a very small black middle class.

Consequently, the disparity in education, income, and arrests in Madison is vast. Just last week, a local progressive newspaper noted that in 2018, blacks made up 43 percent of the city’s arrests, while African Americans comprised only 7 percent of the population.

Clearly, the answer given by both the city and school board are to flatten that disparity by reducing punishment, a move that has created chaos in a once placid city. Of course, the architect of the school discipline plan, former Superintendent Jennifer Cheatham, left the district in August.

After six years as head of the district, she was rewarded with a position as a lecturer at Harvard University.

A school-related issue reared its head during the George Floyd protests, as a caravan of activists drove to School Board President Gloria Reyes’ home to demand police officers—school resource officers—be removed from the city’s public high schools.

The Madison teachers’ union offered a qualified endorsement of removing police from schools, saying the presence of officers triggered “racialized trauma experienced by some of our community members of color.” Previously, the union had supported officers in the school to maintain order.

But the union switched positions only on the condition that the district first hired 33 more support staff (counselors, nurses, psychologists), which, of course, would be new dues-paying members of the union. Evidently black lives matter, but only at a price.

Soon Reyes, a former police officer herself, capitulated to the activists and supported removing the school resource officers from the four high schools.

“The complexities of these times have lasting and painful memories for our students and staff, and we must press harder to dismantle systems that perpetuate racism and create new structures, void of harmful inequities, and with the wellbeing of every student at the center,” Reyes wrote in a statement.

In a twist, support for the police came from an unexpected place. On June 10, a Facebook video of Rhodes-Conway was discovered in which she offers sympathy to police officers, telling them it must be frustrating to be “as committed as I know you are to community policing and to still be criticized for not doing enough.”

The video, which was posted on an internal Facebook page meant for police officers only, was clearly meant to lower the city’s temperature in an attempt to avoid further confrontations.

But when activists saw the video, they were outraged that the mayor would appear to be siding with the cops.

“Does this sound like a woman that understands why black people and white allies across the country keep showing up and out?” wrote the group Urban Triage on its Facebook page.

“Does this sound like a woman that has what it takes to do right by the community? By black people?,” the post read.

Predictably, Rhodes-Conway recorded another video apologizing for the first.

“Black lives matter,” Rhodes-Conway said in the apology video. “I believe deeply in this and yet I failed to center this in my message to the police department,” she said. “I realize that this action has done deep harm to the black community and for this, I apologize.”

But the mayor’s groveling didn’t buy her any goodwill from the group of young activists, who have been raised and educated in Madison to believe they are the ones in charge.

Urban Triage responded by calling Rhodes-Conway a racist and a white supremacist. The group’s Facebook post ended with a simple message for one of America’s most progressive mayors:

“#F—kYourApology.”

Christian Schneider is a reporter for The College Fix and author of 1916: The Blog.