How This Pandemic Proves the Wisdom of the Founders

President Trump raised eyebrows Tuesday when, in answer to a question about whether he could order the revocation of state “lockdowns,” he declared that “the federal government has absolute power.” In reality, no part of the federal government has “absolute” power—or “plenary” power, as Vice President Pence asserted at the same press conference—at any time, even during emergencies. The reason our state and federal constitutions were written was to make that point clear. Instead, our federalist system puts states in the driver’s seat at times like this—and wisely so.

The Constitution’s authors were familiar with epidemics; they were a regular fact of life in the 1780s. And the authorities primarily responsible for taking action back then were state governments, which are closer to the people, more knowledgeable about local conditions, and better able to compare the costs and benefits of their actions. The Constitution they wrote incorporated the preexisting practice of state autonomy on such matters, giving federal officials power over things like matters of foreign relations, but leaving power over public health primarily with the states.

Decentralized decision-making is wise because America is so extremely diverse. The population density in New York City is more than 27,000 people per square mile—10 times the population density of Albuquerque. North Dakota has about four hospital beds per 1,000 people—twice as many as Maryland. The average temperature in Phoenix in April is 85 degrees. In Anchorage, it’s 45. The median age in Utah is 31. In Maine, it’s 45. There’s no sense in using a one-size-fits-all approach for these different places, whether it be to “lock down” or to open up.

And it’s state laws that matter the most, anyway. However much the federal government may have grown in the 20th century, most of the laws relevant to this crisis are enacted by state legislatures, not Congress. The certificate-of-need laws that prevent the construction of hospitals, for example, are creatures of state law. Laws forbidding telemedicine are, too. So are licensing laws that make it harder for people from one state to earn a living in another. Fortunately, many of these laws have now been suspended in light of the epidemic—again, a decision made by states, not by the feds.

Constitutional limits on federal authority aren’t erased during times of emergency. The Constitution gives the president no special set of “emergency” powers, and although the White House can certainly take extraordinary actions in urgent circumstances, its powers are far from unlimited. Probably the most famous Supreme Court decision on this matter is the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer case of 1952, which held that President Truman acted unconstitutionally when he ordered the federal takeover of steel factories when employees threatened to strike. The country was then at war, yet the court emphasized that all presidential authority “must be found in some provisions of the Constitution,” not in some amorphous fountain of “plenary” powers. Since no constitutional authority existed, Truman’s command was void: “In the framework of our Constitution,” wrote Justice Hugo Black, “the President’s power to see that the laws are faithfully executed refutes the idea that he is to be a lawmaker. … And the Constitution is neither silent nor equivocal about who shall make laws which the President is to execute.” Again in 2005, the court held that the president—even in wartime—cannot indefinitely detain American citizens without a hearing. “A state of war,” wrote Justice O’Connor, “is not a blank check for the President.”

But it doesn’t take a Supreme Court opinion to make that point clear. Congress has often asserted its authority during emergencies. During the Civil War, the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War rode Abraham Lincoln’s administration hard, insisting on prosecution of generals who lost battles and double-checking federal expenditures. Congress overrode President Nixon’s veto of the War Powers Resolution in 1973 and later zeroed out funding for the Vietnam War—effectively ending that conflict. Just last month, Congress passed legislation to prohibit President Trump from initiating military action against Iran.

American traditions also make clear that the president’s emergency authority may be broad, but isn’t absolute. The nation has held its regular elections during wars—even during a civil war—and during epidemics such as the 1918 Spanish flu. And while there have certainly been embarrassing instances in which officials have acted unconstitutionally during emergencies, Americans have typically admitted those errors afterward in ways that ensure against repeats of the same abuses in the future. Perhaps the most infamous example of this is the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans during World War II—something the Supreme Court allowed at the time as an emergency measure, despite Justice Robert Jackson’s warning that the decision would become a precedent that “lies about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.” On the contrary, the Korematsu decision was expressly overruled two years ago, in an opinion that called it “gravely wrong” and “morally repugnant” and recognized that the internment had been “objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority.”

Not only does the Constitution recognize no such thing as absolute power, but its federalist structure was designed to leave decisions about domestic crises primarily to state officials. And the coronavirus epidemic is proof of the Founders’ wisdom. Whatever one thinks about how different states have reacted, the decentralized approach is preferable to letting any single politician in Washington, D.C., Republican or Democrat, dictate the terms by which 330 million people approach an unprecedented crisis. Some states have certainly taken wrong steps—it’s hard to defend Hawaii Gov. David Ige’s decision to suspend the state’s sunshine law and public records requirements, for example, or Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s effort to micromanage that state’s population through a series of sometimes self-contradictory orders. But others have taken more moderate approaches that conscientiously balance the risks of infection with the need to maintain the supply of goods and services to the populace. Most welcome have been orders such as those issued by Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey that have suspended restrictions that interfere with the provision of health care, such as licensing laws or limits on pharmacists’ freedom to prescribe medicine.

That’s not to say the federal government has no role to play. Federal bureaucracies that delayed the production and distribution of medical supplies bear a lot of the blame for today’s crisis. The Food and Drug Administration, on the other hand, has taken the welcome step of accelerating its review of investigational treatments. But for the most part, Washington’s job is to support the states. And governors are already considering the best ways to reopen: Several have announced that in the coming days, they’ll produce plans for allowing business to resume while taking appropriate precautions. Some will probably keep fairly strict limits in place, such as requiring travelers from other states to quarantine themselves upon arrival—which states have the legal authority to do. Others may choose to let more people in but impose stricter sanitary standards in public places and prohibit large gatherings. Most likely, state officials will defer to the decisions of county and city governments—which, again, encourages both local decision-making and a kind of competition between officials to find the most efficient way to turn the lights back on.

It’s hard to imagine how the White House could issue a nationwide “open up” order, in any event. The primary federal law governing emergencies is the Stafford Act of 1988, which, again, leaves governors with the primary responsibility for emergencies. Perhaps the only way President Trump could try to override a state’s emergency declaration would be to use Section 5121(B) of that act to declare that a governor’s declaration is itself an emergency, but that would be of dubious legality, since even that section only gives the president power over matters “for which, under the Constitution or laws of the United States, the United States exercises exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority.” That does not include epidemics. Nor does the Defense Production Act allow the president power to revoke state emergency declarations; it expressly does not apply to employment, for one thing. And even if the White House did try to issue a nationwide “open up” order, it would be impossible to enforce, since state authorities could shut down any business they deemed unsafe—and the feds can hardly force workers to come to work if they refuse … or are too sick to do so. The better approach is what the administration has been focused on so far: removing federal barriers to treatment.

The Founding Fathers created a federal government of limited powers—powers they took care to list in the Constitution. Some of these powers, such as the power to regulate commerce, are pretty extensive. But they don’t encompass such quintessentially local matters as health care or the operations of local businesses. As James Madison observed, the Constitution gives the federal government “few and defined” powers, which focus “principally on external objects, as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce,” whereas states have “numerous and indefinite” powers over “all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the State.” This is precisely why President Trump declared in late March that he lacked authority to issue a nationwide “lockdown” order—a statement that brought criticism from the national media but was entirely correct. The same, however, also applies to “open up” orders.

Unlike the rigid, top-down structures of absolute monarchies or dictatorships, our federalist system is resilient precisely because it’s flexible—giving primary authority to the people on the scene, with federal power used as a shield to protect us in the event that local officials act unjustly. And emergencies are precisely those times when we must take care to follow those constitutional rules—instead of disregarding the principles that have seen us through the crises of the past.

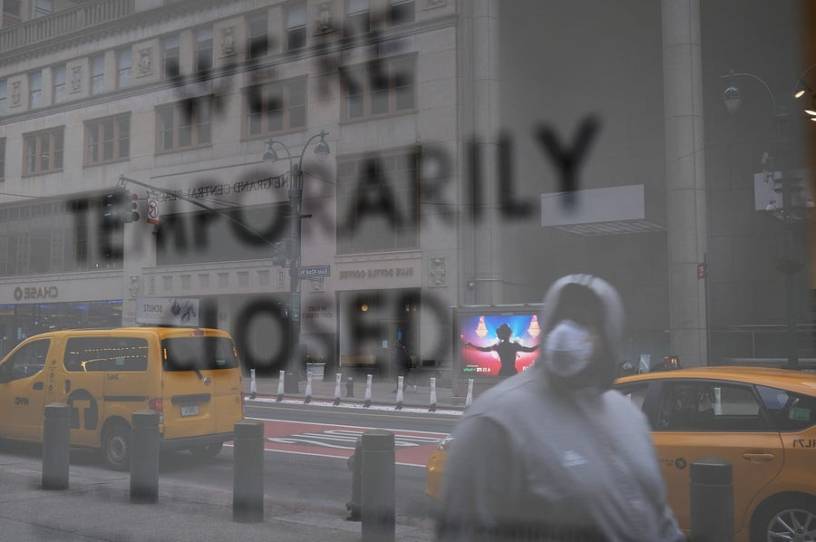

Photograph of a business-closed sign by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.