Timeline: The Regulations—and Regulators—That Delayed Coronavirus Testing

Addressing the media alongside the coronavirus task force on Thursday, Donald Trump said he would “slash red tape like nobody has even done it before” to get approval for coronavirus treatments.

That would be a welcome development indeed. What’s unfortunate is that there was no similar push at the beginning of the crisis to expedite coronavirus testing. The U.S. response to the pandemic has been hampered at every level due to insufficient testing capacity.

The first coronavirus case in the U.S. and South Korea was detected on January 21. Since then, South Korea has effectively contained the coronavirus without shutting down its economy or quarantining tens of millions of people. Instead, the Korean government has pursued a “trace, test, and treat” strategy that identifies and isolates those infected with the coronavirus while allowing healthy people to go about their normal lives. Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan have also managed to contain the virus via a combination of travel restrictions, social distancing, and heightened hygiene.

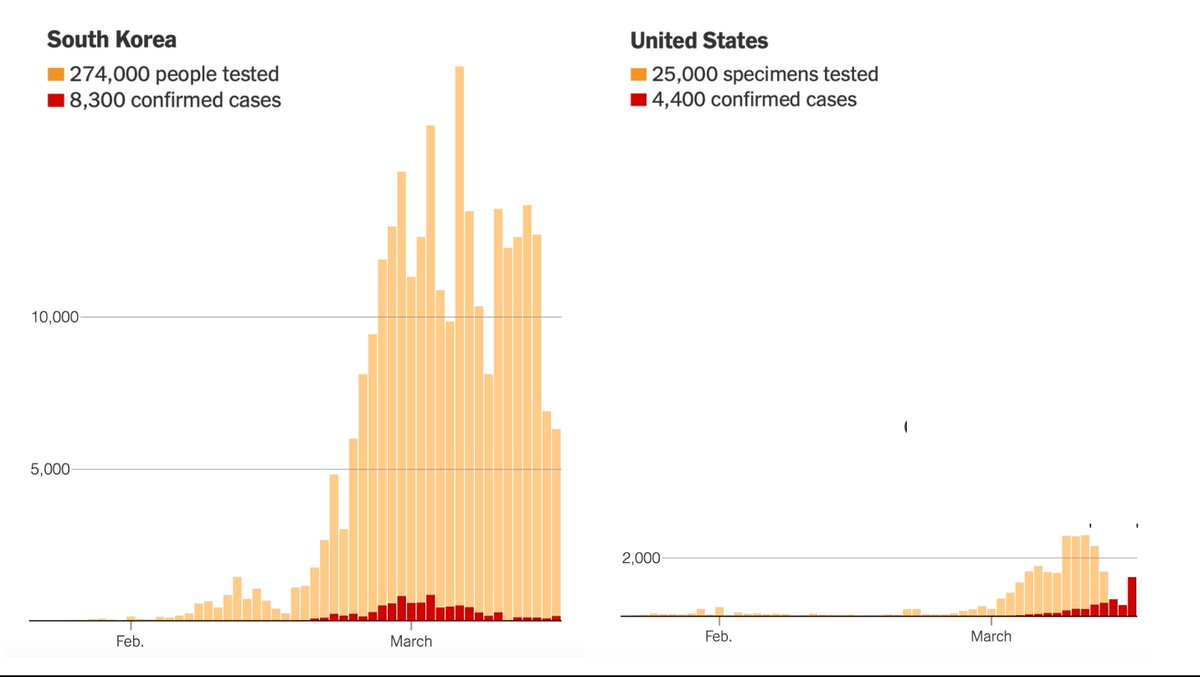

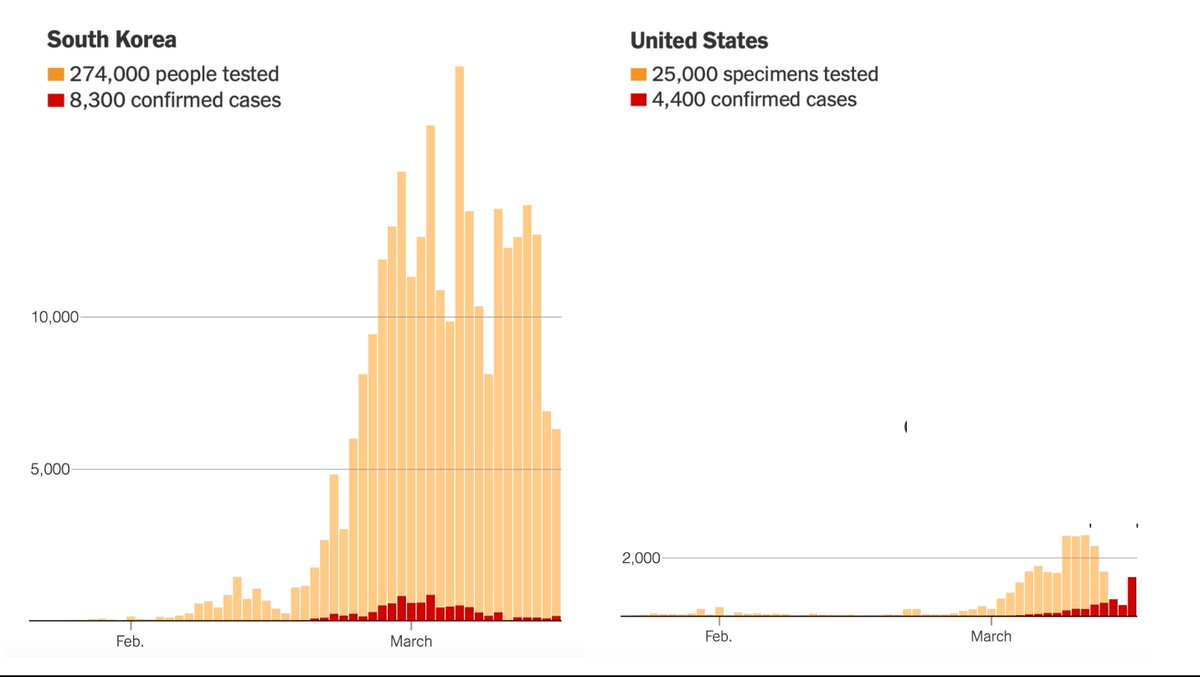

Unfortunately, the United States has not made testing widely available and now various regions are being forced to impose severe economic and social lockdowns. As of March 17, the U.S. had tested only about 125 people per million. South Korea had tested more than 5,000 people per million. Between early February and mid-March, the U.S. lost six crucial weeks because regulators stuck to rigid regulations instead of adapting as new information came in. While these rules might have made sense in normal times, they proved disastrous in a pandemic.

Under ordinary circumstances, the cost of using an imperfect diagnostic test often outweighs the benefit. But when public health officials need to contain a novel and highly contagious disease, speed matters more than perfection. The lessons from this debacle are clear: The FDA needs to have plans in place prior to a pandemic for public labs and private companies to produce their own test kits. A distributed strategy would be much more resilient to errors, in contrast to the single point of failure created by the FDA in this crisis. Poor planning and mindless adherence to peacetime regulations led to this abysmal result:

Source: NYT

Source: NYT

How did the U.S. government only manage to produce a fraction as many testing kits as its peer countries? There have been three major regulatory barriers so far to scaling up testing by public labs and private companies: 1) obtaining an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA); 2) being certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA); and 3) complying with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule and the Common Rule related to the protection of human research subjects. On the demand side, narrow restrictions on who qualified for testing prevented the U.S. from adequately using what capacity it did have.

It’s important to understand the broader context of the FDA regulatory process. It often takes more than a decade for a new diagnostic test or therapeutic drug to earn FDA approval. Fortunately, the FDA already has the ability to let public labs and private companies circumvent the regular approval process under its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) authority. So, why was this emergency authority ineffective in scaling up coronavirus testing? Here is a timeline of the most important events:

December 31: The WHO received reports of dozens of cases of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China.*

January 9: China announced it has mapped the genome of the novel coronavirus.

January 21. The CDC confirmed the first case of coronavirus in the United States in the state of Washington and announced it had finalized its coronavirus testing protocol.

January 23: German researchers published the first paper describing a testing protocol for the novel coronavirus. The WHO would later use this protocol as the basis for the millions of tests it produced for less-developed countries.

January 30: The WHO declared a global health emergency.

January 31: HHS Secretary Alex Azar declared a public health emergency, which initiated a new requirement—labs that wanted to conduct their own coronavirus tests must first obtain an emergency use authorization (EUA) from the FDA. According to reporting from Reuters, the emergency declaration made it more difficult to expand testing outside the CDC:

That’s because the declaration required diagnostic tests developed by individual labs, such as those at hospitals or universities, to undergo greater scrutiny than in non-emergencies—presumably because the stakes are higher.

“Paradoxically, it increased regulations on diagnostics while it created an easier pathway for vaccines and antivirals,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. “There was a real foul-up with diagnostic tests that has exposed a flaw in the United States’ pandemic response plan.”

This was the moment when the wheels came off the bus. Keith Jerome, the lab director at the University of Washington Virology Lab in Seattle, told The New Yorker how perverse this heightened standard was from a public health perspective:

From the point of view of the academic labs, we look at it, like, when there’s any run-of-the-mill virus that people are used to, they trust us to make a test. But when there’s a big emergency and we feel like we should really do something, it gets hard. It’s a little frustrating. We’ve got a lot of scientists and doctors and laboratory personnel who are incredibly good at making assays. What we’re not so good at is figuring out all the forms and working with the bureaucracy of the federal government.

EUAs were intended to speed up the normal authorization process. But in this case, labs that were already conducting their own coronavirus tests needed to cease operations until they were granted an EUA. By declaring a public health emergency and not waiving EUA requirements, the FDA was actually slowing down the testing process.

Obtaining an EUA is no quick task. The FDA requires new protocols to be validated by testing at least five known positive samples from a patient or a copy of the virus genome. Most hospital labs have not even seen coronavirus cases yet. An article in GQ magazine detailed how Alex Greninger, an assistant director of the clinical virology laboratories at the University of Washington Medical Center, was forced to navigate a regulatory morass:

After emailing his application to the FDA, Greninger discovered that it was incomplete. It turned out that in addition to electronically filing it, he also had to print it out and mail a physical copy along with a copy burned onto a CD or saved to a thumb drive. That package had to be shipped off to FDA headquarters in Maryland. It was a strange and onerous requirement in 2020, but Greninger complied. He had no choice. On February 20, he overnighted the hard copies of his application to the FDA.

But submitting the physical application wasn’t the end of the process. Before granting the EUA, the FDA wanted Greninger to run his testing protocol against the MERS and SARS viruses:

Greninger complied. He called the CDC to inquire about getting some genetic material from a sample of SARS. The CDC, Greninger says, politely turned him down: the genetic material of the extremely contagious and deadly SARS virus was highly restricted.

“That’s when I thought, ‘Huh, maybe the FDA and the CDC haven’t talked about this at all,’” Greninger told me. “I realized, Oh, wow, this is going to take a while, it’s going to take several weeks.”

February 3: The FDA hosted a previously scheduled all-day conference at its headquarters with regulators, researchers, and industry leaders to “discuss the general process for putting diagnostic tests cleared under emergencies on the path to permanent approval by the FDA,” according to reporting by Reuters. “Though coronavirus was now the hottest topic in global medicine, a broadcast of the meeting conveyed little sense of urgency about the epidemic sweeping the globe” and the virus was only mentioned “in passing.”

February 4: The FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the CDC’s test to be used at any CDC-qualified lab. Prior to issuing the CDC an EUA, all tests had been collected in the field and then shipped to CDC headquarters in Atlanta for analysis. During this time period, the CDC was able to run only about 500 tests (12 of which came back positive). To implement nationwide testing, the CDC would need to distribute its testing kits to partner labs across the country.

In a declared emergency, the FDA has broad discretion about which laboratory-developed tests will be permitted to be used. By only issuing a single EUA to the CDC, the FDA put all its eggs in one basket. Alan Wells, the medical director for the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s clinical laboratories, told the Wall Street Journal: “We had considered developing a test but had been in communication with the CDC and FDA and had been told that the federal and state authorities would be able to handle everything.”

February 5: The CDC began shipping test kits to about 100 state, city, and county public-health laboratories across the country, which would have allowed 50,000 patients to be tested. However, most of the partner labs ran into problems during the validation stage (which is necessary to ensure the tests were functioning properly), according to a ProPublica investigation:

The [CDC] shunned the World Health Organization test guidelines used by other countries and set out to create a more complicated test of its own that could identify a range of similar viruses. But when it was sent to labs across the country in the first week of February, it didn’t work as expected. The CDC test correctly identified COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. But in all but a handful of state labs, it falsely flagged the presence of the other viruses in harmless samples.

The specific cause of these problems is still under investigation, but the initial findings suggest there were problems with one or more of the reagents used in the CDC testing kits. The CDC paused testing at its partner labs and resumed exclusive — and very limited — testing at its Atlanta headquarters.

February 10: The CDC notified the FDA about the reagent problems in the testing kits it had shipped to its partner labs. By not allowing private companies or public labs to use their own tests, the FDA had created a single point of failure and ultimately delayed large-scale testing by weeks. Keith Jerome, the lab director at the University of Washington, explained to The New Yorker why the FDA’s plan was vulnerable from the outset:

The FDA’s exclusive authorization to the CDC to conduct COVID-19 tests ended up creating “what you’d think of as an agriculture monoculture. If something went wrong, it was going to shut everything down, and that’s what happened.” Jerome said that his lab has taken its own steps to mitigate this problem. “We’ve built three completely independent testing pathways in our laboratory, so that if there’s a shortage of a reagent or a bit of plastic, we have other ways to do the testing.”

February 21: Nancy Messonnier, the director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) at the CDC, told journalists that the issues with the reagents were still not resolved.

February 24: An association of more than 100 state and local health laboratories sent a letter to the FDA commissioner asking for “enforcement discretion” to use their own lab-developed tests. The chief executive of the association that sent the letter called it a “Hail Mary” pass and an act of desperation. The FDA directed the labs to submit an EUA application instead.

Between mid-January and February 28, the CDC produced more than 160,000 tests but used fewer than 4,000.

February 29: Facing a backlash to its rollout of testing, the FDA reversed its position and removed the requirement that advanced laboratories obtain prior emergency use authorization before using their own tests. At the time, this exemption applied only to “laboratories that are certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.” One researcher estimated 5,000 virology labs in the country met this standard. For context, U.S. testing capacity includes approximately 260,000 laboratory entities.

March 3: Vice President Pence announced the CDC was lifting all federal restrictions on who can be tested for COVID-19: “Any American can be tested, no restrictions, subject to doctor’s orders.” Previously, testing was limited to only those who were exhibiting symptoms and had recently traveled to China or had been exposed to a known case. However, the supply of tests in particular regions would continue to be the most common binding constraint.

March 12: The FDA issued an EUA to Roche. Paul Brown, the head of Roche’s Molecular Solutions division, told The New Yorker, that “the company had been working on a test since February 1st” and that “the new tests, which are mostly automated, can make it possible for large testing companies such as Quest and LabCorp to test for COVID-19.” The CDC and state and local public health labs have been running tests manually. Reaching the scale of millions of tests will require automated tests on high throughput machines at large testing companies.

March 13: President Trump declared a national emergency. The FDA issued an EUA to Thermo Fisher.

March 15: HHS Secretary Azar waived sanctions and penalties against any covered hospital that does not comply with various provisions of the HIPAA Privacy Rule related to patient privacy and consent, including the need “to obtain a patient’s agreement to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care.” Previously, HIPAA privacy provisions and the Common Rule were holding up testing and the dissemination of information. According to an article in the New York Times, these kinds of requirements prevented labs from conducting coronavirus tests on samples collected for research purposes:

Federal and state officials said the flu study could not be repurposed because it did not have explicit permission from research subjects; the labs were also not certified for clinical work. While acknowledging the ethical questions, Dr. Chu and others argued there should be more flexibility in an emergency during which so many lives could be lost. On Monday night, state regulators told them to stop testing altogether.

…

On a phone call the day after the C.D.C. and F.D.A. had told Dr. Chu to stop, officials relented, but only partially, the researchers recalled. They would allow the study’s laboratories to test cases and report the results only in future samples. They would need to use a new consent form that explicitly mentioned that results of the coronavirus tests might be shared with the local health department.

They were not to test the thousands of samples that had already been collected.

March 16: The FDA expanded the EUA exemption to all commercial manufacturers and labs using new commercially developed tests, not just those that are certified to perform high-complexity testing under CLIA. The FDA also devolved regulatory oversight of these labs to the states. Wojtek Kopczuk, a professor of economics at Columbia University, quipped that the “FDA sped up the process by removing itself from the process.” The FDA also issued EUAs to Hologic and LabCorp. Co-Diagnostics, a molecular diagnostics company based in Utah, already had a test available in Europe and claimed it could supply 50,000 coronavirus tests per day going forward under the new FDA exemption. On Monday, government officials announced they were going to set up more drive-through testing centers. By the end of the week, they said they expect to have 1.9 million tests available thanks to high throughput automated machines at commercial labs.

Lessons learned.

In her call with reporters on February 21, Nancy Messonnier, who runs the CDC’s research on immunization and respiratory diseases, said: “We are working with the FDA, who have oversight over us, under the EUA, on redoing some of the kits. We obviously would not want to use anything but the most perfect possible kits, since we’re making determinations about whether people have COVID-19 or not.” This mentality is understandable coming from a regulator under ordinary circumstances. In normal times, and with non-highly contagious diseases, many of these regulations related to testing make sense. However, during a global pandemic, the risk calculus shifts. As Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of the WHO’s health emergencies program, said in a press conference last week, when battling a new virus, “speed trumps perfection.”

The FDA did the right thing when it expanded the EUA exemption to all labs and manufacturers and devolved regulatory oversight to the states. The Department of Health and Human Services did the right thing when it waived certain provisions of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. But all of these actions were six weeks too late. Policymakers should consider implementing an automatic trigger so these decisions are made immediately upon the declaration of a public health emergency. COVID-19 will not be the last public health emergency. Speed, not perfection must be the focus of government agencies who are entrusted to protect the health of hundreds of millions of Americans. A distributed approach would be much more resilient to the inevitable mistakes and accidents inherent to pandemic response. Instead, in this crisis, the FDA bet big on a single testing protocol from the CDC and burned its ships. And when the “perfect” test failed spectacularly, everyone was left wishing for a way to retreat.

Alec Stapp is the director of technology policy at the Progressive Policy Institute.

Photograph by Al Drago/CQ-Roll Call/Getty Images.

*Correction, March 23, 2020: The piece originally misspelled Hubei Province.