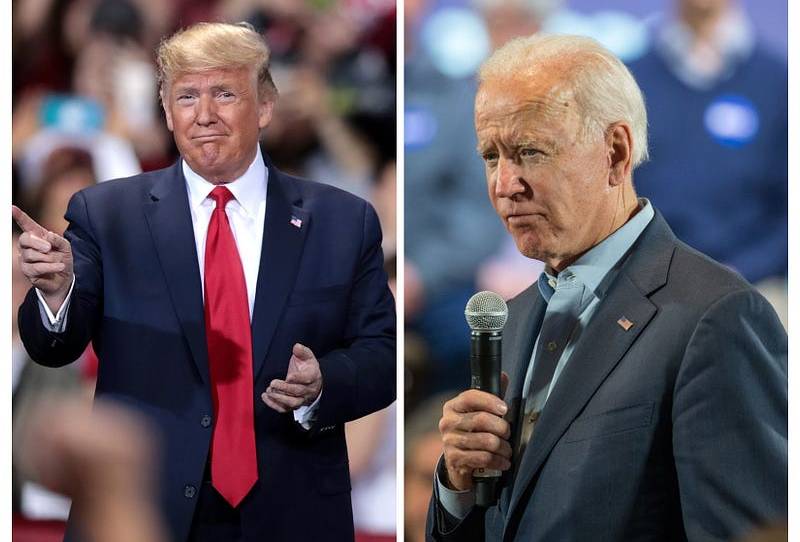

Will 2020 Be a Realignment Election?

“Twenty weeks is an eternity in politics; a lot can change if we demand more now” is what I have been telling my students as we talk online about the seemingly endless problems that are hitting the nation: Our ongoing pandemic and economic recession have been eclipsed, at least momentarily, by social unrest that the nation has not seen in generations. And it’s taking place in an environment of uncompromising political extremes.

The question, then, is whether or not the alarming polarization that we are currently living through can be repaired if one party or leader is able to take advantage of this moment and actually builds a meaningful new coalition that breaks with the status quo position of cancelling and demonizing the opposition.

The stage is set for a fall electoral realignment because the United States is already in the midst of numerous significant, path-changing events that are facilitating a real transformation of extant party ideologies and leaders. We are seeing a shift in which issues matter, an alteration of the structure or rules of the political system, and a non-trivial swing in the demographic bases of power that typically support political parties.

From racial equity and community safety protests on the left and extreme, tone-deaf executive orders on the right—including orders that hurt families and orders in the name of border safety or withdrawing from certain treaties and alliances—values are being contested and are changing and numerous political institutions are being reformed. Moreover, just 20 percent of Americans are satisfied with the direction of the country, government dysfunction and a lack of leadership is considered the greatest problem facing the country sans COVID-19, and Americans have been moving away from both the Democratic and Republican parties for decades.

The open issue, as I tell my students, is what happens in the precarious 20 weeks leading up to the election itself. Will tribalism continue to grow and in doing so quash room for debate, difference, and disagreement or will a new, diverse coalition emerge that actually brings Americans together and moves the country forward?

At present, the rhetoric of leaders on both the right and the left—from the mass protests in our cities to the Oval Office—has taken a path of uncompromising aggression to the point of demonization of outsiders, a refusal to listen and hear others. One could imagine a realignment of unambiguous polarization where the world after November is one where the parties simply govern without regard to those outside of their bases and the party in power simply ignores the needs and interests of the minority party, akin to the first two years of the Trump administration. Such a move would set the stage for the nation to swing regularly from one set of extreme policies to another from election to election with increasing numbers of executive orders and never-ending litigation. This would create massive anxiety and puts our nation’s stability in peril as the country cannot persevere indefinitely as one group celebrates while another seethes.

The obvious alternative to this unwelcome scenario would be a movement or leader who can take a page from American history and recall that real, stable social change emerges from coalition-building and compromise. After all, the major socio-political achievements in the past few eras, from the 1977 food stamp program to the Reagan-era reforms in Social Security and taxation to the more recent Americans with Disabilities Act, CHIP, and the McCain-Feingold Act, were bipartisan initiatives that developed from a spirit of compromise and recognition that many voices needed to be heard and considered to create robust change.

Most notably, the landmark Great Society legislation of the 1960s was spearheaded by President Lyndon B. Johnson without liberals backing him. It transformed the political landscape with the Voting Rights Act, and Civil Rights Act, the war on poverty, along with numerous other initiatives such as Medicare and Medicaid. We can debate the efficacy of these programs, but the processes by which they happened are worth studying: There were numerous battles to move these acts forward and they required various religious, labor and civil rights interests along with entrenched state and regional party bosses to buy into the programs. Despite violence, deaths, and social unrest, the varied groups worked together, because they knew that the only way to move society forward was to hear each other and work with one another.

President Johnson, unlike the present administration which declares law by executive order and ignores large segments of the population entirely, knew that he could not bring diverse groups together and create meaningful change through such orders and this lesson is certainly applicable today.

The present, callous disregard and damning of those who disagree only creates more resentment and instability. But there is time before Election Day for leaders—even if it not in the Oval Office—to emerge and set a better tone with respect to working through the nation’s deep and often understandable differences.

For instance, while COVID-19 has been politicized by the media and some politicians, Americans are not deeply divided when it comes to real, concrete safety measures to mitigate the virus and protect Americans and the socio-economic fall-out from the pandemic will last for years. Similarly, while the magnitude will need to be worked out, there is essentially universal agreement on the need for police reform and even Donald Trump supported reform with his own recent Executive Order. Moreover, Americans are fairly united on policy ideas of access and opportunity. Majorities of Americans now believe that individual efforts are not enough to guarantee equality and instead hold that structural issues must be addressed to promote more equity in society. So there are openings to have real, albeit difficult discussions, where the proper attitude can bring people to the table and mutual interests still exist that can form the basis of policy change.

History has shown that America has been able to find common ground on contentious and divisive issues. I have seen our nation’s so called “liberal” college students, for instance, routinely reject the extreme positions of parties along with their winner-take-all approaches to politics. Undergraduates regularly show a commitment to a pragmatic center of policy priorities and there is no reason the nation cannot do the same nor has to accept this deep political divide going forward. Let’s not waste these crucial upcoming weeks and move from the rhetoric of exclusion to one of inclusion before this critical election polarizes the nation further.

Samuel J. Abrams is professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.