Hi and happy Sunday.

Most of us are probably familiar with the term “brain drain” and how it’s affecting Africa, whose population is skewing younger and increasing rapidly. By 2050, 1 in 4 people on earth will be African, according to estimates by the United Nations. But the continent’s economies are providing far too few jobs for young professionals, leading to spikes of emigration to the West and elsewhere.

In the medical field—especially in remote and rural palces—this leaves under-resourced groups with too few doctors to treat ever-growing needs. But against the new backdrop of a now-shifting U.S. stance on foreign aid, doctor and writer Matthew Loftus says a decades-old network is helping fill holes Africa’s brain drain has created: Hospitals founded by Western missionaries are now teaching a rising generation of African health providers who want to stay home.

A message from The Pillar

Get smart, serious, faithful Catholic news—delivered to your inbox!

Are you Catholic? Do you want Catholic news that’s actually worth your time? The Pillar is smart, serious, faithful coverage of the Catholic Church. We’re a subscriber-funded publication focused on investigative reporting, analysis, interviews, and a daily news roundup delivered right to your inbox. With faithful Catholic journalists around the globe, we report on the Church because we love the Church.

Matthew Loftus: How Mission Hospitals Are Combating Africa’s Medical ‘Brain Drain’

Soon after President Donald Trump took office in January, cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) dismantled some of the most effective foreign aid programs in the world. There has been much (justifiable) outrage about abruptly cutting off lifesaving care while a treatment that could end HIV as we know it is just coming on to the market. But there are other public health problems that few international development agencies or Western governments have dealt with.

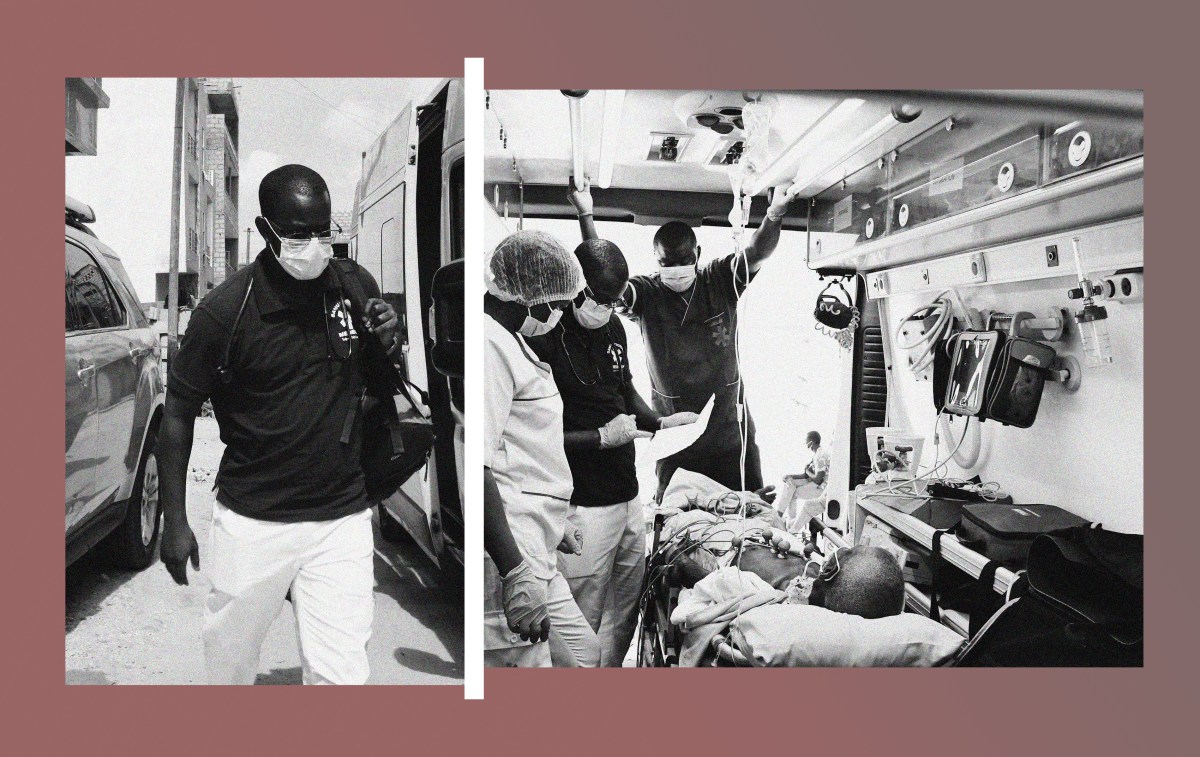

One of the biggest challenges facing Africa in particular is training doctors in low-income countries and then keeping them in the workforce there. What may be a surprising solution are not-for-profit mission hospitals founded decades ago by Western missionaries who came here to preach the good news. The earliest generations of medical missionaries went overseas as preachers who happened to be doctors, followed by doctors who were focused primarily on providing medical care to people in need. Now those of us going from the West to places like Africa are focusing our work on teaching medical professionals and equipping them to teach the next generation.

To understand the challenge we’re trying to meet, imagine you’re a doctor in sub-Saharan Africa. After finishing your required schooling and a one-year internship in a teaching hospital, you forgo higher pay elsewhere to return to your hometown to work at your local government health facility—because your community needs it.

A regular sight at hospitals like this one is the long queue of patients at the retail pharmacy across the street. Family members of hospital patients are purchasing IV fluids and antibiotics to bring to their loved ones because the hospital is out of stock. The local health authority has been promising for several weeks that a new shipment of drugs is coming “soon.”

A nurse urges you to hurry to the emergency room where you find a young man who has been in a motorcycle accident. He’s likely bleeding inside his brain. There’s a CT scanner at a city hospital 25 miles away, but the one county ambulance is transporting a pregnant woman somewhere else and won’t be back for a while. During your internship you observed a craniotomy to relieve pressure inside the skull, but you’ve never done one yourself. The nurse is asking you whether to start prepping the patient to go to the operating room, but as you’re trying to decide what to do, the power goes out. After waiting a few hours for power to be restored, you do your best to imitate the procedure you’ve seen before and pray your patient will survive.

The next day, dejected, you call the county health authority who hired you to talk about the urgent needs for manpower and equipment at the hospital. The person you talk to laughs and tells you he can arrange a job transfer to a better hospital in the city, but you’ll have to pay him a bribe equal to roughly three months’ salary. The next time you pick up your phone you see a Facebook ad for a placement agency that will help you find a job in Europe or North America, and you wonder if you’d be better working there and sending your family part of your salary every month.

This is a hypothetical situation, but health care professionals in sub-Saharan Africa face challenges like these every day. Broken systems and a severe lack of resources plague facilities across the continent, with low pay and little support from authorities. The Lancet estimates that nearly a decade ago about 5 million deaths per year across the world were attributed to low-quality care, with an additional 3.6 million deaths due to people not being able to access medical care. The health equity gaps between Africa, especially among Africa’s poor, and the rest of the world are still mind-boggling. Not a week goes by in my work as a family physician in Kenya where I don’t see someone suffering a miserable outcome because they weren’t able to access or afford the care that they needed.

Thousands of doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are trained in the countries where they are needed every year, but many of them leave. This “brain drain” (now referred to politely as “human capital flight,” though I’m not sure this label is less demeaning) is a problem for many low- and middle-income countries, but especially for Africa. While specific numbers are hard to come by, more than half of all doctors trained in some small African countries have emigrated to another country to work. The ratio of nurses who emigrate is lower in most countries but the number of nurses leaving still often exceeds the number of nurses needed to safely provide care to the population.

This challenge has lots of potential solutions, though none are simple. But one key element is equipping well-trained doctors to be leaders who can help transform their health care systems—and to stay where they’ve been trained.

Mission hospitals have stepped up to perform this critical role. When they started a century ago, these facilities were mostly staffed by Americans or Europeans as part of their efforts to spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ far and wide. They were usually part of holistic efforts: Most mission compounds had schools and churches to help meet both physical and spiritual needs of local populations. Over the years, the numbers of foreign missionaries have dwindled as Africans have built up their capacity to practice medicine and grown their own churches.

The old paradigms of white people coming in to proselytize and inject penicillin are a thing of the past. Mission hospitals nowadays are now performing laparoscopic surgeries and providing EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy for survivors of PTSD. The preaching, teaching, and healing of 20th century missionaries was so successful that most mission hospitals are now surrounded by large populations of Christians, and the local denominations that now oversee these hospitals don’t have a single Westerner in charge of anything. In many cases, mission hospitals are the most accessible providers of medical care in rural areas, such as The Luke Commission in the small country of Eswatini in southern Africa.

Mission hospitals are getting squeezed, though. Government facilities and private hospitals have become the dominant health care providers over the last century, but the quality of many facilities varies.

With health care costs rising and fewer missionary doctors (who represented free labor) coming to sub-Saharan Africa, providing medical education is now one of the most important functions of mission hospitals. Organizations like the African Mission Healthcare are doing much-needed work to support mission hospitals financially, but the new paradigm will require the missionaries going to work in mission hospitals to be educators—teaching and training the next generation of African doctors.

One of the most important organizations that has made this a reality is the Pan-African Academy of Christian Surgeons. PAACS, a nonprofit founded by missionary surgeons, funds surgical training programs in 12 African countries and has seen 150 surgeons graduate over the past two decades. In a few cases, they’ve managed to double the number of surgeons working in a particular country.

It’s important to recognize that medical education works very differently in many of these countries than in most Western countries. In many places, a doctor who wants to train as any kind of specialist must pay fees to a university, which grants them a master’s degree in their desired specialty after four or five years of clinical training. It’s great for training academic physicians and surgeons who can work in big cities, but by design it limits the number of doctors getting specialty training by shutting out hospitals that aren’t part of university systems. It also forces doctors to moonlight while completing a grueling residency. Both of these factors have contributed to the huge disparities in the number of health care workers serving African communities as well as health outcomes for those communities.

The PAACS model remedies many of the challenges while adding value in other ways. Thanks to the generosity of its donors, including MedSend, PAACS funds the entirety of a surgical resident’s training period, allowing them to focus on their studies without having to work elsewhere to make ends meet. They sponsor conferences that allow residents, faculty, and graduates to share knowledge, encourage one another, and develop their teaching skills. They worked closely with their surgical colleagues throughout Africa to collaborate with an accrediting body (the College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa) that allowed their graduates to be considered certified surgeons just as their university-trained peers are.

PAACS also requires residents to agree to stay in Africa and serve needy communities for at least five years after graduation, but most stay for far longer. According to Keir Thelander, executive vice president of PAACS, about 30 percent have become teachers at the hospitals where they trained, some have gone to work for government facilities, and a handful have even become missionaries themselves, supported by their local churches to serve in even needier parts of Africa. I personally had the opportunity to see the multiplying power of Christian service and medical education when I spent several years working at AIC Litein Hospital, a mission hospital in Kenya, with the first PAACS graduate to start a new PAACS program run entirely by Africans.

There are still big challenges to overcome. Mission hospitals and our faith-based training programs will always be one small part of a larger health care ecosystem. But based on my experience in family medicine education, developing a large health care workforce willing to work in places that others find undesirable and sacrifice lifetime earning potential in order to provide health care to the poor is greatly aided by both the example of Jesus and the power of the Holy Spirit. Mission hospitals don’t always have the resources necessary to provide everything our patients need, but we all work together as a community to support and encourage each other when things get overwhelming. Some African missionaries will have to be funded primarily by Western donors like MedSend’s Launch Project, especially since larger health bodies like the World Health Organization and other grantmaking organizations are still not funding higher-level health education at appropriate levels. Cuts to foreign aid will have downstream effects—for example, USAID was building a new apartment building for trainees at the hospital I work at before funding was abruptly cut off in January. Primary care education, like the family medicine program I’m working in, is still not as strong as surgical training programs like PAACS.

While there are many discouraging stories about global health these days, PAACS is an extremely bright and heartening example of what can be done with the little that’s available. My colleagues and I are so grateful to see good things happening as people are trained, and we’re looking forward to the day when the generation we’ve been teaching surpasses us in their eagerness to serve and missionary zeal.

SCOTUSblog: Court allows parents to opt their children out of school lessons involving LGBTQ+ themes

Our colleagues over at SCOTUSblog have had a busy week rounding up the latest Supreme Court opinions. Friday featured several high-profile cases, including Mahmoud v. Taylor, which centered around a group of parents’ challenge—on religious liberty grounds—to their local school system for not accommodating their desire to opt their kids out of LGBTQ+ content at school. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the parents, with the opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito. Here’s a bit of Amy Howe’s analysis:

In a 41-page opinion that was accompanied by color reproductions of pages from the storybooks, Alito explained that the school board’s use of the storybooks—along with “its decision to withhold notice to parents and to forbid opt outs—substantially interferes with the religious development of their children and imposes the kind of burden on religious exercise that” the Supreme Court found unacceptable more than 50 years ago, in a decision, Wisconsin v. Yoder, that ruled for Amish parents challenging a Wisconsin law that required children to attend school until the age of 16.

The school board, Alito wrote, “requires teachers to instruct young children using storybooks that explicitly contradict their parents’ religious views, and it encourages the teachers to correct the children and accuse them of being ‘hurtful’ when they express a degree of religious confusion.”

When a policy imposes a burden like this, Alito continued, it is subject to the most stringent form of review, known as strict scrutiny, which asks whether the policy “advances ‘interests of the highest order’ and is narrowly tailored to achieve those interests.” Although the board may generally have a compelling interest, as it argues, in maintaining a safe and non-disruptive learning environment, Alito acknowledged, the board’s argument is weakened by the opt-outs that it allows in other scenarios – for example, from sex education. “This robust ‘system of exceptions’” also “undermines the Board’s contention that the provision of opt outs to religious parents would be infeasible or unworkable,” Alito wrote.

Quick Questions With Ryan Burge

Political scientist Ryan Burge either writes for or is quoted by just about every news outlet covering religion in some way, shape, or form—including us. His popular Substack, Graphs About Religion, in which he dissects and analyzes data and social science, is a must-read for anyone seeking to understand how religion intersects with any number of other facets of American life (and beyond). I wanted to ask Burge about some newish religious story trends and some other big-picture issues. My questions to him are in bold, below.

What trends do you think will come to characterize American religion in the next few years? For example, will it become younger and more masculine? More or less centralized?

I think the most compelling (and underreported story) in American religion right now is the meteoric rise of non-denominationalism. Even into the early 1990s, it was an incredibly small part of the population—just 3 percent of all respondents to the General Social Survey. Today, nearly 15 percent of adults are non-denominational, and it’s one-third of all Protestants. The implications of this is a much more fragmented evangelical movement that will be harder to track, measure, and describe.

Several news stories in recent years have reported that young people—men in particular—are turning to more traditional faith traditions such as Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. Is there more to some of the underlying data that some of these reports are missing?

The best way to describe those types of news stories is anecdotal. In terms of Eastern Orthodoxy, the entire tradition has fewer than 700,000 members nationwide. So, if they reported the addition of 5,000 young men, that’s a pretty noticeable jump in the world of Eastern Orthodoxy. But in the grand scheme of things, this is just a drop in the bucket. For instance, the Southern Baptists have lost 3.6 million members just since 2006.

There’s a lot of wishful thinking happening in conservative news outlets right now. They’ve learned that stories about any type of religious growth tend to generate a lot of clicks, likes, and shares. The “same old story” about American religion isn’t going to garner much attention. But it’s always important to put those statistics in a larger context.

Why are young men generally becoming more religious than young women?

This is an important point to clarify—it’s not statistically accurate to say that young men are more religious than young women. A much more accurate framing is that for decades women were more religious than men on a variety of metrics. Among Gen Z, the gender gap on measures of affiliation and attendance has narrowed significantly.

The upshot is simply this: A Gen Z man is probably just as likely to be religious as a Gen Z woman. This, given the last 50 years of survey data, is pretty unprecedented. Why this is happening is a much more difficult question to answer. Politics is certainly playing a role, and I will be writing about that in more depth in the future.

What are the best ways to measure religious affiliation among Americans? What is the relationship between church attendance and faith?

There’s no perfect way to measure religious affiliation. Denominational statistics on membership are notoriously problematic. Trying to get thousands of churches to submit a one-page report of statistics can prove to be a herculean task. Also, those organizations have little incentive to actually “clean up” their rolls by culling members who have been inactive for years.

The other option is just to ask people about their religious affiliation on surveys. That seems pretty straightforward until you realize that a huge portion of Americans don’t know what the word Protestant means. Especially since the word “evangelical” doesn’t even have a widely accepted definition, you can see how this method is flawed as well.

If one reads the academic literature in the sociology of religion, the one facet of religiosity that seems to be the most beneficial is religious attendance. People who regularly attend religious services express higher levels of political tolerance, have a greater propensity to gain civic skills, and often live longer lives. Unfortunately, it’s the one religious metric that seems to have faded the most in recent years.

You’ve been studying religion and data for a long time. What’s a question (or more than one question) that you haven’t been able to find a satisfactory answer to yet?

I think that the average person would be completely flabbergasted by just how little data we actually have when it comes to religion. For instance, there’s almost no good survey data on American religion prior to 1970. And, even when modern surveys like the General Social Survey (GSS) began, the sample sizes were really limited. In the first wave of the GSS, which was fielded in 1972, there were 83 non-religious respondents in total. It’s hard to learn much about a group when the sample size is so small.The other hindrance has been that very few surveys spent a considerable amount of time on religion. My two favorite datasets, the aforementioned GSS and the Cooperative Election Study, were not designed with the primary goal of measuring religious trends over time. I am working on a number of projects that will hopefully make it much easier to answer many of the more elusive questions about the religious lives of Americans in the future.

More Sunday Reads

- For Christianity Today, Andy Olsen writes about the consequences of President Donald Trump’s campaign to deport asylum seekers who came to the U.S. from places like Iran, fleeing religious persecution. That includes congregants of pastor Ara Torosian’s Farsi-speaking congregation at Cornerstone West Los Angeles. “On Tuesday, the pastor recorded on his phone as masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents arrested two of his church members on a Los Angeles sidewalk. The Iranian husband and wife had pending asylum cases, according to Torosian. They fled Iran for fear of persecution for being Christians and had been part of his congregation for about a year. The detentions add to a growing number of church members and Christians seeking religious protection who get picked up by ICE. Often they have no apparent criminal history. In many instances, they were in the United States lawfully, complying with orders from immigration courts. ICE has traditionally not deported individuals with pending asylum petitions, who are allowed to work while their cases proceed.”

- Iranian mullahs have made the destruction of Israel a primary theological goal. But, it was not always so. For The Jewish Chronicle, Hussain Abdul-Hussain reconstructs the history of Iranian Shiism and how Iran’s hardline religious leaders incorporated the Palestinian cause into their doctrine. “In 1928, Hasan al-Banna, a schoolteacher in Egypt, founded the Muslim Brotherhood, whose guiding principle was the revival of the pan-Islamic caliphate with the mission of spreading Islam, by any means necessary, including violence. Banna therefore started arming the Brotherhood and training its members. When the Egyptian government busted him, he found in the ‘liberation of Palestine’ a good excuse to justify his illegal militia. Government agents assassinated Banna in 1949. He was succeeded by his rival, another schoolteacher, Sayyid Qutb, who proved to be even more radical than his predecessor. Qutb’s books defined the militant Islamist movement – especially its hatred against Jews. The man who translated Qutb’s works from Arabic to Farsi was a young Shia cleric in Iran. His name was Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran today. Khamenei’s mentor, Khomeini, imported Qutb’s thought into Shiism and came up with his controversial theory about an Islamic government in which the state is guided by one cleric. The singularity of the cleric at the helm of the state broke with a millennium of Shiia religious decentralisation. For over 1,000 years, the Shia agreed that their clerics would guide the believers, but only on spiritual issues, until the return of the Mahdi, Muhammad al-Mahdi, Arabic for ‘the divinely guided one.’ The Mahdi, a messianic figure, was the twelfth imam who in Shiite tradition had gone into occultation and would return at the end of times to restore justice on earth. Until his return, the Shia pledged allegiance on temporal matters to whichever sovereign was in power.”

Religion in an Image

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.