Welcome back to Dispatch Faith.

How do we properly grieve national tragedies like the deaths of campers and staff at Camp Mystic in Texas, following this month’s devastating floods? What does it mean to mourn the loss of a loved one, the dissolution of a marriage, or the shattering of a dream?

So much in our current age and American culture tempts us not to grieve such things well and deeply, contributing writer Hannah Anderson writes this week. Sure, we attend vigils, observe remembrances, and sometimes offer (sincere) platitudes. But do we let tragedy reshape our moral imaginations? If that sounds somewhat vague, Hannah poses some penetrating questions in this week’s essay that, though somber, are much needed.

One housekeeping note: Dispatch Faith won’t be in your inboxes next week as I’m taking some time off. But it’ll be back on August 3.

A message from The Pillar

Get smart, serious, faithful Catholic news—delivered to your inbox!

Are you Catholic? Do you want Catholic news that’s actually worth your time? The Pillar is smart, serious, faithful coverage of the Catholic Church. We’re a subscriber-funded publication focused on investigative reporting, analysis, interviews, and a daily news roundup delivered right to your inbox. With faithful Catholic journalists around the globe, we report on the Church because we love the Church.

Hannah Anderson: The Grace of Grief

Three weeks ago, I took a spiritual retreat to Texas Hill Country. It was my first time in the area, and I was captivated by the natural environment: I’d wash the dusty heat of the day away with a swim in a river of turquoise. At night, the sky filled with stars and the moon had never looked quite so spherical. After a season of upheaval in my personal life, I felt a sense of safety, as if I were somehow being held by earth and sky.

Five days after I left, torrents fell from that same sky and swept away sleeping children.

At the time of writing, the death toll of the July Fourth flooding around Kerrville, Texas, had reached 134 with more than 100 other people still missing. Hope at this point means a proper burial and a chance to say goodbye. But as quickly as the skies turned, the shock of the news turned to public debate. “Thoughts and prayers” gave way to political scrutiny and moral grandstanding. A city official in Houston was removed from her position when she cynically framed the tragedy in racial terms, while others used it to prove a point about the Trump administration. Some even turned to blaming the victims themselves, including those from Camp Mystic, where at least 27 campers and counselors perished.

It’s natural to seek answers when tragedy strikes. We want to make sense of things and ensure that it never happens again. But even if natural, moving too quickly to debate and analysis can inflict further pain on those already suffering. Even more counterintuitively, it can also stunt our own moral development: Doing so makes it easier to bypass the harder work of grieving and the wisdom it holds for us.

Permission to grieve.

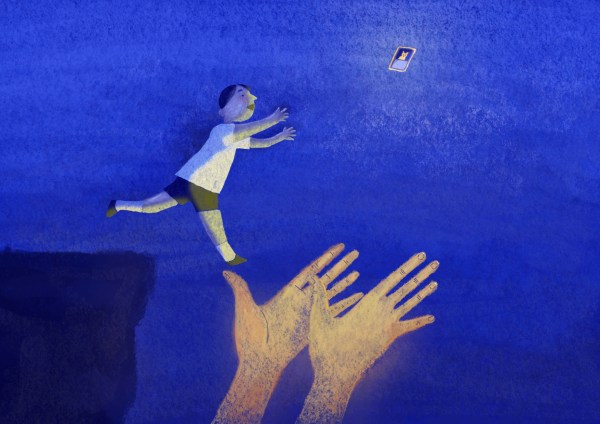

Each tragedy includes a moment when reality settles in—when you understand that the child is lost, the marriage is over, the diagnosis is terminal. In my own life, I’ve imagined this moment as the beginning descent into a steep canyon, that moment when you feel the ground begin to slope and you know that the path is leading you downward. With each step, the canyon walls rise higher and higher. You know you are moving forward, but it is not progress as we typically understand it; you are moving toward the very thing you most want to avoid. As the walls grow steeper, the sun is eclipsed and the shadows lengthen. Soon enough, you’re in darkness, and you’ve lost the ability to orient yourself. You may be at the bottom, but you cannot know, so you stumble in the black and doubt whether the road will ever rise and lift you to light again.

No wonder we do everything in our power to avoid walking this path.

But when it comes to grief, Americans are at a particular disadvantage. Our unique cultural story (by no means absent of suffering) has also been shaped by an overarching forward momentum, a positivity that says the future is bright and just within our grasp. The United States is, after all, the land of promise: the land where folks can hope to build a quiet, stable life, where hard work is rewarded, where children are nourished and can grow up in safety so that their children never know want. That’s the dream anyway, and it’s created a distinct kind of spirituality.

Duke Divinity School professor Kate Bowler has studied the phenomenon of this unique spirituality (sometimes named “prosperity gospel”) and how it emerges from and reinforces American culture. Her popular-level work, Everything Happens for a Reason, explores how our expectation of blessing leads us to respond to, or in many cases, gloss over grief. Lacking the epistemological or existential resources to sit with suffering, we end up offering each other platitudes (like “thoughts and prayers”). Or we talk about everything around a tragedy except the grief we feel. We debate, report, castigate and blame—anything to avoid the one thing we need to do above all else: grieve.

Part of the problem is that we misunderstand the extent of the grieving process. In the days and weeks after a tragic event, we may find solidarity and emotional release in public memorials, candlelit vigils, and the outpouring of condolences on social media. But the work of truly grieving takes longer. Grieving in its fullest sense is a reforming of the imagination, a figuring out how to exist once certain ways of being have been made impossible. It is learning how to live in a world your child has been taken from. It is learning how to crawl in bed alone once again. And how to crawl out of it again in the morning. It is the work of letting suffering transform our moral imagination, making us more humble, more grateful, more generous people. In other words, if we can remain the same people we were before tragedy struck, if we immediately fall back to our previous battle lines, we have more than likely minimized grief and bypassed its vital work.

As I look at the current political moment, I’m struck by how much of our civil unrest can be traced back to an inability to walk the path of grief and imagine life on the other side. The significant losses of my lifetime alone include 9/11, the 2008 economic crash, COVID-19, January 6, and the rapid deterioration of institutional norms. For others, the losses are more ambiguous, ongoing, and unresolved: an increasingly unviable work economy, crushing student debt, delayed marriage and family, fractured community, developmental and educational delays, gun violence in classrooms, the resurgence of virulent racism, antisemitism, sexism, and relationships destroyed by political partisanship and conspiracy. Put more simply, the loss of the American Dream.

To grieve such things as a nation would require that we name them as real, acknowledge that many things have indeed been lost to us, and allow that sorrow to humble us. It would require that we release our certitude and confidence in ourselves. But this would also strike at the heart of a spirituality that says if we just work hard enough, live faithfully enough, we will have success. In short, truly grieving our losses would reform our imagination about civic life entirely.

So instead, here we sit with decades of accumulated, unresolved, unnamed grief, prey for opportunistic leaders who have the intuition to see our pain but lack the moral character to help heal it. Some of us have become desperate for the past and the return of realities we once trusted in (or at least thought we could trust). Others press toward a transhuman future, willing to exchange our very humanity for the promise of wealth, health, and safety—anything, just so long as it keeps us from suffering. Just so long as we don’t have to undergo true re-formation.

The possibility of hope.

A particular theory of grief suggests it doesn’t actually fade over time, but that we have the capacity to grow so that our particular losses take up less space in our lives and are easier to bear. As already alluded to, research shows that grieving is deeply connected to learning and change; it is the process of imagining a new way of being in the world, not despite our loss, but because of it. In this way, grieving itself can become the catalyst that expands the register of our imaginative possibility, and learning to grieve may be the path to a new kind of American Dream—one forged not in stoic overcoming or scapegoating, but through the common human experience of suffering.

This was the approach of the late Nikki Giovanni, a poet whose own futuristic vision rested on the necessity of grieving. Unlike the transhuman vision of folks like Peter Thiel or Elon Musk, who attempt to bypass suffering, Giovanni believed that the path to the future demanded we learn to grieve as a means of preserving our humanity. In “Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea (We’re Going to Mars),” Giovanni takes up the question of space exploration, likening it to similarly historic ventures. But then she makes a surprising move: She suggests that those best suited to lead us in the future are those who have suffered in the past—not because it’s their turn to lead, but because they have learned something through grieving that the rest of us haven’t yet. Speaking of the millions of souls condemned to the Middle Passage, that brutal transatlantic crossing from Africa to New World slave colonies, Giovanni writes:

They had no idea which way “back” might be

there was nothing in the middle of the deep blue water to

indicate which way home might be and it was that

moment … when the decision had to be made:

Do they continue forward with a resolve to see

this thing though or do they embrace the waters

and find another world

In the belly of the ship a moan was heard … and someone

picked up the moan … and a song was raised … and that song

would offer comfort … and hope … and tell the story…

They need to ask us: How did you calm your fears … How

were you able to decide you were human even when everything

said you were not … How did you find the comfort in the face

of the improbable to make the world you came to your world …

How was your soul able to look back and wonder

I myself can’t help but wonder how developing our collective capacity to grieve—our ability to hear that song of lament sung in the belly of the ship and be changed by it—might alter our current political fragmentation, preserve our humanity, and offer us a path forward. Singing that song will not take away our grief, but it might allow us to take the next natural step in grieving toward hope and a new way of being Americans together. Hope will not come from avoiding hard things or blaming others; it will come in naming our grief and walking toward it. It will come from acknowledging our own weakness and limitations, being honest about the fact that none of us can withstand the rushing waters that remake our lives. And we will need leaders who, instead of taking advantage of our unresolved grief, can guide us by their steady, stable presence—leaders who have faced the darkness and developed the moral imagination to guide us to the other side. So that when we take that next step in, with, and through grief, we will discover that the canyon must also have an ascent—and that what goes down must come up.

More Sunday Reads

- Amid the grief and tragedy of Camp Mystic in Texas were also stories of hope and heroism. For the Washington Post, John Woodrow Cox (masterfully) tells the story of 19-year-old camp counselor Ainslie Bashara, who led her cabin of campers through the flood waters and to safety in the early hours of July 4. “Down the hill, Ainslie saw a cabin that housed some of the littlest girls. In the windows, the beam of a flashlight swirled. Between her and them was the water, which had surged now almost to the pavilion. Over the roar, she could hear the girls begging for help. ‘The sounds are just horrific,’ she said later. ‘And you can’t do anything.’ They scrambled atop benches until the water reached those, too, and the counselors guided the group to the foot of a steep, rocky hill. ‘Get ready to climb,’ they told the girls, some of whom, like Ainslie, had forgotten their shoes. But they had to go, even as rain battered their faces. Ainslie felt like she was clambering up a waterfall. Each time the river rose and they had to hike to a higher spot, the counselors counted their girls again: 16, 16, 16. … Nowhere had Ainslie’s faith grown more than at Mystic, a place that, to her, felt holy. Hours earlier, the counselors had performed skits. One group had spoofed ‘Wicked’ and another ‘Love Island,’ Ainslie said, but her group had decided on ‘Jesus Highlights.’ She played the disciple Peter, caught in a boat amid wind and waves when Jesus encouraged him to believe that he, too, would not sink. ‘Fear not, Peter, for I am with you, even in the storm,’ Ainslie had written in the script for the friend who played Jesus.”

- The Rev. John MacArthur, who influenced generations of evangelical pastors and worshippers, died Monday at 86. Daniel Silliman wrote his obituary for Christianity Today: “MacArthur said the most important mark of his ministry was that he explained the Bible with the Bible, not cluttering up sermons with personal stories, commentary on current events, or appeals to emotion, but teaching timeless truth. The longtime pastor of Grace Community Church said a good sermon should still be good 50 years after it is preached. ‘It isn’t time-stamped by any kind of cultural events or personal events,’ MacArthur said. ‘It’s not about me. And it transcends not only time, but it transcends culture.’” He wasn’t without controversy, facing criticism over the years for his position on doctrinal questions, the role of women in the church, and the handling of domestic abuse. But as Silliman put it, “The waves of controversy, decade after decade, did not notably limit MacArthur’s influence.”

Something Different

To switch things up this week, instead of a religion-related image, I hope you’ll enjoy a performance from this week’s MLB All-Star Game. As a fan of the Atlanta Braves (whose home ballpark hosted this year’s midsummer classic), I’m biased. But I think Atlanta tenor Timothy Miller has the best rendition of “God Bless America” out there. He usually performs at every home Sunday Braves game but was featured Tuesday night in front of a national audience. Enjoy.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.