Hi and happy Sunday.

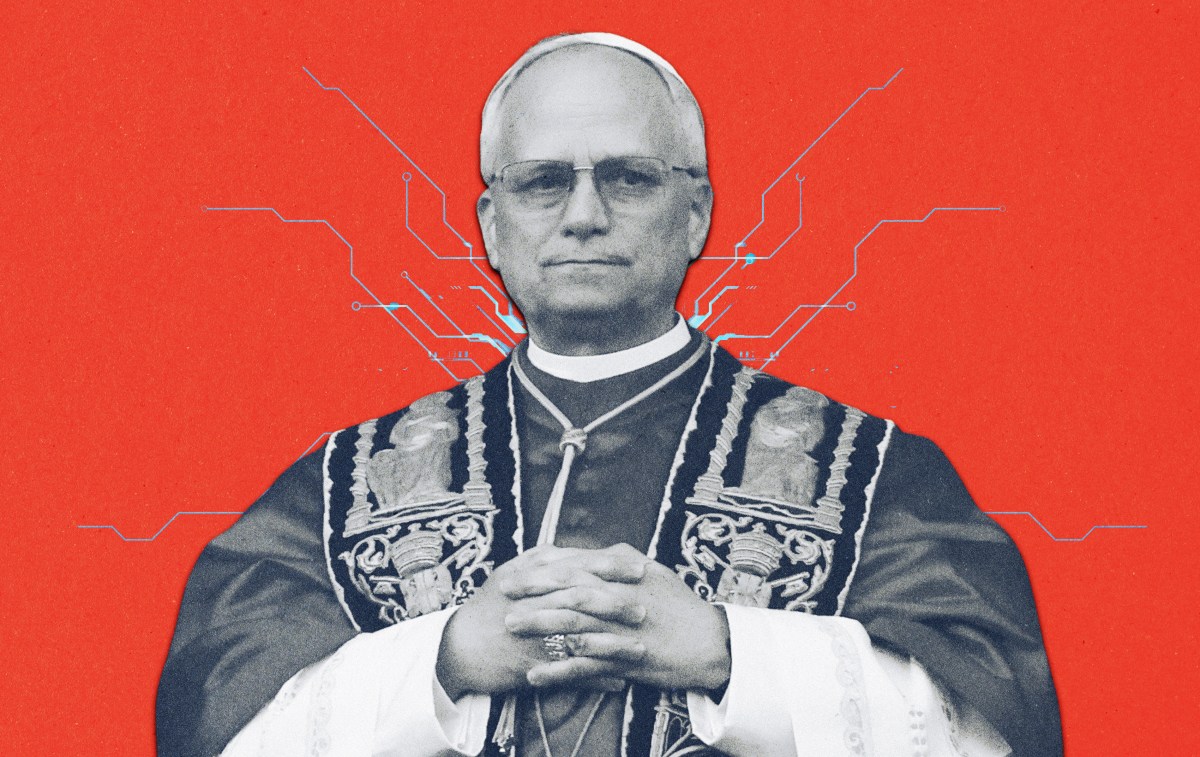

The rise of artificial intelligence is a topic on just about everyone’s minds these days, and we’re no different, as evidenced by the debate we published this week on the subject. In today’s Dispatch Faith, Patrick McNamara asks whether Pope Leo XIV will leverage his position and theological insight to attempt to slow the march of AI. But to more clearly discern whether that will happen in the future, we must look to the past, he argues.

Patrick McNamara: Will Pope Leo XIV Slow the AI Blitzkrieg?

Does God have competition with AI? Peter Thiel, one of Silicon Valley’s most influential voices, described the evolution of AI on Joe Rogan’s podcast in August 2024 saying, “If we got AGI (artificial general intelligence), if we got, let’s say, super intelligence … that would be interesting to Mister God because you’d have competition for being God.”

Artificial intelligence will be the most transformational and impactful technology that current generations will endure, for better or worse. As the leader of the world’s billion-plus Catholics and steering all the political, social, and financial influence of the Catholic Church, Pope Leo XIV is one of a few people who can influence its development, if he so chooses. Of the handful of people poised to shape AI, Pope Leo XIV’s influence, if any, is the most obscure, so it’s important to consider what papal influence on AI might entail.

He seems poised to do so. Pope Leo XIV has described AI as another industrial revolution. In his first public address to the College of Cardinals, he explained the reasoning behind his choice of name as a blend of timing and impact. “Mainly because Pope Leo XIII in his historic encyclical Rerum Novarum addressed the social question in the context of the first great industrial revolution,” he said. Pope Leo XIV strives to reimagine Pope Leo XIII’s impact to the next industrial revolution in the field of artificial intelligence and modern times, as he made clear in his first address: “In our own day, the church offers to everyone the treasury of her social teaching in response to another industrial revolution and to developments in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges for the defence of human dignity, justice, and labour.”

While so much of the conversation around AI focuses on the future, the answer to our question about papal influence on AI lies in the past. Specifically, we should go back to the 1890s to explore Pope Leo XIII’s impact on his generation’s Industrial Revolution. Only then can we look to the future.

Pope Leo XIII’s groundbreaking Rerum Novarum, published in 1891, spoke in the heat of the industrial revolution, laying a stake in the ground on controversial topics from private property and capitalism to unions and socialism. “The social doctrine of the Church developed in the nineteenth century when the Gospel encountered modern industrial society … The development of the doctrine of the Church on economic and social matters attests the permanent value of the Church’s teaching,” the Catechism of the Catholic Church says, hailing Rerum Novarum (RN) as the foundation of Catholic social thought and one of the first economic documents.

Three attributes of Rerum Novarum stand out:

- In an age of war and revolution, Rerum Novarum was a profound text, upsetting both capitalists and socialists.

- Pope Leo XIII prioritized human dignity over economic gains and efficiency.

- Rerum Novarum was theologically provocative enough to equip lay Catholics to organize and mobilize in preservation and expansion of Catholic values.

Rerum Novarum opens with a diagnosis of inequalities that plagued the world, heralding the scientific breakthroughs of the day while recognizing the extreme wealth of a few and the poverty of the many. While socialists sought to abolish private property, Pope Leo XIII argued for its preservation: “The fact that God has given the earth for the use and enjoyment of the whole human race can in no way be a bar to the owning of private property.” This sentiment landed poorly with socialists at the time, but it lucidly laid out the Catholic Church’s economic stance on private property for the whole world.

But Pope Leo XIII also denounced robber barons and argued for the establishment of societies that protect workers’ rights and take care of the vulnerable. “Riches do not bring freedom from sorrow and are no avail for eternal happiness, but rather are obstacles, that the rich should tremble at the teachings of Jesus Christ,” he wrote. Amassing more money is a burden, not a virtue, he argued, and when one has an abundance of money, one should be considering the needs of others, not personal gain. Pope Leo XIII was no capitalist patsy.

As unions swung between being invigorated by membership and crushed by opposition, Pope Leo XIII honored the work of groups that supported the working man and his widow or orphan. Revering the medieval guilds of old, he called for unions to become “more numerous and more efficient”—modern unions that could advocate for workers’ rights in the current times. This gave legitimacy to unions as a whole and offered a framework for how Catholics would participate in unions or create their own, not to grab power but to advocate for justice and human dignity.

In polarizing times, it’s easy to upset one side, but it’s difficult, and even intriguing, when one is able to upset both sides in one swipe of the pen. Rerum Novarum was a profound piece with bite that laid practical, specific economic stakes in the ground on behalf of the Catholic Church.

Rerum Novarum also prioritized human dignity over efficiency or economic gains. Language invoking “human dignity” can be vague, lacking specific applications, but not for Pope Leo XIII. He goes into granular detail that work must not prevent religious duties, strain family commitments, or result in health issues due to excessive labor. He lays a foundation for what is and isn’t respecting the human dignity of the worker, calling for special protection for the poor and destitute. Prioritization of the vulnerable, a value often left to private groups in any capitalist theory, is one of the core attributes of this theo-economic text.

Most importantly, Rerum Novarum is provocative—biased toward action. It catalyzed social movements, gave the workers’ rights movement religious backing, and set a precedent for future papal doctrines’ ability to critique economic systems. A practical example of how Rerum Novarum mobilized Catholics comes from the Catholic Workingman’s Club, founded by Albert de Mun, a conservative Catholic. Prior to RN’s publication, the club had 18,000 members in 1873. But by 1900, after RN’s publication, it had nearly quadrupled to 60,000 members. “After the publication of Rerum Novarum de Mun could cite the authority of papal encyclical,” historian Francis Sicius wrote.

Pope Leo XIV now has a similar opportunity. Rerum Novarum was a groundbreaking text, and in a similar vein, any Roman influence on Silicon Valley would require an inaugural text on technology.

What would such an influential text entail?

A profound polemic on AI would provide a code of technology for all people to hold accountable any individual, company, political party, or country that advocates for AI development and financial gain over human flourishing. Early writings on AI from Catholic writers and the Holy Father himself highlight emerging themes of truth, human dignity, vocation, justice, and anti-violence as core to human flourishing. These are explicitly named in the Maryland conference of bishops’ framework for AI and mentioned in Pope Leo XIV’s message to the second annual Rome Conference on AI, which gathers AI, religious, and political leaders to focus on the ethical challenges of AI. As Pope Francis argued, “The inherent dignity of each human being and the fraternity that binds us together as members of the one human family must undergird the development of new technologies and serve as indisputable criteria for evaluating them before they are employed.” If companies like OpenAI and Anthropic develop technologies opposed to these values, could the Catholic Church provide guidance on what constitutes a violation of human dignity and how to resist them?

For example, Axios recently reported on a Carnegie Mellon study around AI technologies and how it affects children. “Used improperly, technologies can and do result in the deterioration of cognitive faculties that ought to be preserved,” the study notes. These AI companies have strong financial incentives to push their tools to every school and every child in the world, regardless of developmental effects on children. A Papal encyclical could provide a framework and structure for when AI technologies are appropriate and when they are harmful. This could function similarly to how driving poses unique risks to younger people, so driving education is introduced in a structured way with education, guidance, and practice, ensuring human lives are protected and dignity respected.

Second, we can expect Pope Leo XIV to continue the tradition of prioritizing the vulnerable, the poor, and the marginalized. How does AI affect the oppressed in totalitarian countries? Will farmers in Central America be worse off? How will factory workers fare when AI is introduced to their environment? If AI can shield people from hazardous work, from monotonous tedious labor, and liberate them to live out a more purposeful life, this could be a beautiful world with AI. Mark Zuckerberg’s Personal Superintelligence manifesto describes a world like that, but it’s fair to wonder if big tech companies—which have traditionally profited off children, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups (see the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma or the Wall Street Journal’s reporting about Instagram knowing their platform was toxic for young girls)—will suddenly change their tune in the AI era. Any papal work would flesh out who should be prioritized and protected and how, ensuring people and human dignity are prioritized over profits.

In modern times, can the pope still mobilize the world to action? From Pope John Paul II’s anticommunism movements, to Jubilee—a sacred year in which millions of Catholics make a pilgrimage to Rome—the papal seat has mobilized millions in hinge moments in history. Is Pope Leo XIV able to be provocative enough to sway the world? If the full weight of the Catholic Church—with its political, cultural, and financial influence—is mobilized on AI, would it move the needle? I don’t gamble, but I’d bet even tech titans like Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg would be surprised at the force of the strike.

As a kid from Chicagoland and a revert to the Catholic Church, I’d love to see Pope Leo XIV bend the evolution of AI toward truth, justice, and human dignity. However, I run a venture capital-backed startup, and zeal is erupting for AI in ways far surpassing what one finds at a local Mass on a Sunday. Trillions of dollars and the world’s most powerful people are backing it. It’s an AI blitzkrieg.

Like his namesake, Pope Leo XIV has an opportunity to shape history, not just write about it. But he better move quickly.

Valerie Pavilonis: Can We Be Earnest Again?

We live in an age of irony—of not fully meaning all we say we mean, often with a wry smirk, says Dispatch Ideas Editor Valerie Pavilonis. But seeing how earnestness contrasts with today’s ironic age helped her understand more fully what true belief is, as she writes in a piece on our site today.

Indeed, nowadays you are hard-pressed to express earnestness without some sort of caveat. A juvenile example is those sweatshirts declaring “Virginity Rocks!” that went viral when I was in college a few years ago. The trend appears to have begun with the YouTuber Danny Duncan, who began wearing such a sweatshirt as a joke and who told the New York Times: “I have sex, obviously, but I want people to do whatever they want to do and not be pressured into anything.”

More seriously, last year Christian writer Wendell Berry opined on a lack of unequivocal expression in an essay on war and the death of children. “Who in public life could quote without fear or embarrassment any saying of Jesus on the subject of peace?” he wrote. “Martin Luther King Jr. could do so, and did so. But who now?”

Note that Berry applies this to public life. It would be fine in most Christian circles to quote Jesus on peace; not doing so, in fact, would be quite odd indeed. But in public life I have noticed that I clam up—I feel odd mentioning my spiritual experiences to nonreligious friends, even though these experiences are a major shaping force in my life.

She writes later:

One might also draw lessons from religious figures. Last year, the theologian Erik Varden wrote well of Cardinal Jean Daniélou, the French Jesuit who ministered to prostitutes in the mid-20th century: “He did not, by being a friend to prostitutes, relativize Catholic teaching: he wrote strongly in defense of chastity. But he was not shy to visit and assist those who, to reach this ideal, had a long way to go. He was just acting like his Master.” Indeed, he was not shy. And neither was Christ—public preacher, bread-breaker, and life-giver that he is.

Varden did not write only about Daniélou; that bit was part of a fuller meditation on chastity, in which he also wrote: “Only what I love will change me beautifully.” You cannot really love, I think, without being honest. Love requires a willing, enthusiastic force behind it, a fullness that cannot form if the germ of the feeling is cocooned in layers of irony. Perhaps that’s why a child’s sense of love of the small things of the world, of this teddy bear or this doll, is so heartwarming to us: They do not care if it is cool, or if anyone is watching. They are simply honest in their love.

More Sunday Reads

- Like many faith traditions, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is grappling with what to do about members’ exits from the church becoming influential on social media. For the Wall Street Journal, Georgia Wells covers the so-called “exmo” (ex-Mormons) movement from the perspective of those leaving and from the church itself. “The flood of videos from #exmo influencers question church rules banning same-sex marriage, previous policies that barred Black men from the priesthood until 1978 and current restrictions on leadership positions for women. ‘When your content is all about problems with the church, it’s kind of hard to dismiss it,’ said Benson Lawson, 20, who left the church last summer after finding #exmo content on social media. Lex Ivarsson, who goes by ExmoLex on social media, said she had been posting to YouTube for a year about her decision to leave the church, with videos garnering thousands of views. When she posted on TikTok, her third video received more than a million views. ‘TikTok shocked me,’ Ivarsson said.” Meanwhile, leaders within the church try to combat the online movement. “David Snell, 33, tries to address controversial questions about church history and provide what he sees as a faithful perspective on what the #exmo community is saying. Based in Utah, he hosts a prominent podcast, called Keystone, sponsored by an LDS nonprofit. ‘If the only place you are getting information about the faith is from people who have left it, chances are you are probably not seeing a lot of reasons people choose to join and stay in the church,’ Snell said.”

- In Tablet, Dovid Bashevkin meditates on what Judaism tells us about idolatry, from biblical times to the current age. “Here lies one of the most profound transformations in history: The human instinct to seek God directly was withdrawn. God became hidden, in every way imaginable: Not only did idolatry vanish, but, as the Vilna Gaon explains, so did prophecy. Both rested on the same foundation: an instinctive search for divine meaning. Prophecy gave language to the transcendent, while idolatry gave it a concrete shape. No wonder the Torah’s first mention of prayer is interpreted by Rashi as the first mention of idolatry. Both were born of the same yearning: to connect to God. Once that yearning was removed, so too were both prophecy and idolatry. The philosopher Karl Jaspers called this shift the ‘Axial Age,’ when humanity moved from a God-centered world to a self-centered one. Whereas previously societies were grounded with a shared sense of mystery and wonder for the divine, there was a shift to a more self-centric universe.” Later Bashevkin writes: “My rebbe, Rav Ezra Neuberger, put it more succinctly: We have more in common with the rabbis of the Mishnah than with a common Jew from the age of prophecy. Like Rav Ashi speaking to Menashe, we peer through modern eyes, trying to understand a world that instinctively sought transcendence. Whether through prophecy or idolatry, people once looked beyond themselves to answer life’s ultimate questions. Now, stripped of both idols and prophets, we know only how to look within.”

Religion in an Image

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.