Hi, happy Sunday, happy Labor Day weekend, and happy college football season. (Go Vols!)

If you haven’t made your way over to our website in the last couple of days, you missed our new-and-improved design. We obviously hope it helps you, dear reader, in enjoying everything The Dispatch has to offer. If you have any questions about it, you might find your answers here.

This week’s Dispatch Faith returns to a theme we’ve tackled several times before: the relationship between faith and the rest of our lives. Bonnie Kristian argues that religious faith necessarily makes demands on how public figures conduct their public business because how we answer life’s ultimate questions cannot really be privatized. Her launching points for the argument are three fairly high-profile controversies from this summer.

Bonnie Kristian: Chip and Joanna Gaines, ‘Private Religion,’ and the Whole-Life Demands of Faith

You’d be forgiven for missing it, but this summer has seen a small swarm of controversies concerning the boundaries and acceptability of religion in public life.

In different ways, each of these stories turns on the nature of faith: Is it essentially a hobby? Kind of a fandom, maybe, or an intellectual interest, or a book club with unusual rules? Perhaps religion is an unusually venerable and meaningful pastime, but one nevertheless to be pursued only in suitably private places: the home, the sanctuary, and explicitly religious institutions where everyone is present on an opt-in basis.

Or, as people of faith are wont to contend, is that a ridiculous and ignorant description—a fundamental misunderstanding of how religion works?

I guess I’ve shown my hand already, so I may as well say: I’m in the latter camp. Faith is not a private matter that can be confined to mind or locked away in small and specialized spaces, what National Review’s Michael Brendan Dougherty once dubbed a “religious autonomous zone.” It demands to shape entire lives.

And how could it not? I’m a Christian, but I think this must be true for any serious adherent of any religion. If you sincerely believe you have solid information on the nature of God, the universe, and humanity’s duty, purpose, and design, you can’t forget that when it’s time to go to school or work. Conviction can’t be flicked on and off like a light switch. It doesn’t work that way. The whole thing is of a piece, a swirl of belief, belonging, and behavior that cannot be disentangled.

As Pope Leo explained last week, “Our faith is authentic when it embraces our whole life, when it becomes a criterion for our decisions, when it makes us women and men committed to doing what is right and who take risks out of love, even as Jesus did.”

That’s not to say sincere faith is a get-out-of-jail-free card, neither figuratively nor literally. To give the easiest example, no amount of religious conviction gives you the prerogative to murder. But most examples—in fact, none of the four stories from summer 2025 that I want to tell you—are not that easy.

I don’t share these stories to argue that faith should get you carte blanche to do whatever you like in any and every setting, regardless of the consequences for other people. My contention is narrower: that our increasingly post-religious society cannot be allowed to forget how religion works in the lives of believers. Without that understanding, the First Amendment’s free exercise clause will be a dead letter, with religion forever on the light end of the scale when we try to balance competing rights.

The first of the four is from July, when lifestyle influencers and TV stars Chip and Joanna Gaines premiered a new reality show. It starred three families, one of them a gay couple with twin boys. Now, the Gaineses have long been known as fairly conservative Christians—as David French recalled at the New York Times, a decade ago Buzzfeed was breathlessly informing the reading public that the Gaineses attended a church “firmly against same-sex marriage.” So the casting decision of the gay couple was met with criticism and dismay from prominent evangelicals online.

That critique was unfair, argued French (who’s a former senior editor at The Dispatch and who wrote a very kind foreword to my last book) in his column at the Times:

Think of the sense of entitlement here. On one hand, evangelicals say, “How dare you discriminate against us in the workplace,” and then turn around and tell a fellow evangelical couple, “You’re betraying us unless you discriminate against gay men at your job.” Evangelicals aren’t a superior class of citizen. We don’t get to enjoy protection from discrimination and the right to discriminate at the same time.

Only, it’s not employment discrimination to decide not to feature a gay couple as one of just three families on your TV show. It’s reality TV. They’re not actors. Their lives are the show, their selves the characters, their image the brand.

This decision was an affirmative choice, a statement of some kind. Whether it’s a political or theological message or simply an attempt to broaden the show’s commercial appeal, I can’t say. But declining to proactively feature a gay couple on your reality show is not “discriminat[ing] against gay men at your job”—it’s not like firing your longtime bookkeeper because you happen to learn he has a boyfriend. Respectful pluralism doesn’t mean religious people need to have amnesia whenever they’re on the clock.

The Christian fans who thought the Gaineses shared their belief that God reserves marriage for one man and one woman were not wrong to be surprised at this entirely elective choice. If the Gaineses seriously held that belief, this choice would be surprising, because conviction isn’t supposed to wither under such gentle challenges as being wealthy and wildly successful television producers.

The second story is set in Seattle, where a court ruling in late May held—as legal scholar Eugene Volokh put it—that a “Women-Only Naked Spa Lacks First Amendment Right to Exclude Transgender Patrons with Penises.”

This is a traditional Korean nude spa run by conservative Christian immigrants. It has been a female-only space because patrons use a sauna and receive treatments in a common area, and the owners have the modesty ethics you’d expect from their faith.

The federal court’s ruling, which Volokh says seems to correctly interpret the relevant state law, treats that faith as irrelevant. The spa’s owners are required to check their beliefs at the door of their own establishment. They “begged the government not to force them to violate their Christian belief in modesty between men and women,” wrote one judge in a dissenting opinion. But their “pleas fell on deaf ears,” and now, “under edict from the state, women—and even girls as young as 13 years old—must be nude alongside patrons with exposed male genitalia.”

The majority opinion’s response to the religious argument is revealing. The spa owners’ “religious expression is only incidentally burdened,” it says, because they aren’t prohibited from “expressing [their] religious beliefs.” That is, they can still say they don’t think unmarried male and female people should be nude together; they just can’t do anything to preclude that happening in their spa.

But it’s hardly incidental to be legally banned from doing what you believe God requires of you. Even the minority of Americans likely to support an anti-discrimination law targeting single-sex spaces this way should be troubled to see religion crammed into so small a corner. Free exercise of faith requires more than expression; that’s why it has its own constitutional clause, separate from protection of speech.

For the third story, we’ll cross over to England, where in June a Catholic member of Parliament, Chris Coghlan, posted his indignation that his Catholic priest asked him to act like a Catholic.

At issue was the U.K.’s assisted dying bill, which Coghlan supports and his professed faith opposes. (The Catechism of the Catholic Church says that “[i]ntentional euthanasia, whatever its forms or motives, is murder,” and suicide too is forbidden.) If he voted for the bill, Coghlan’s priest warned, he’d be denied the sacraments. He voted for it anyway, was denied accordingly, and took to X to announce that his “private religion will continue to have zero direct relevance to [his] work as an MP representing all [his] constituents without fear or favour.”

In fairness to Coghlan, who was promptly dogpiled, he’s not wrong to want to represent his constituents without bowing to pressure from outside organizations. His mistake is supposing that the Catholic Church—for a professing Catholic—is an outside organization. His mistake is supposing there’s such a thing as “private religion,” that the faith he claimed could be thus walled off from his work as a lawmaker.

Admittedly, public religion becomes more complicated when the state is involved (as compared to a market situation, like the reality show, or what should have been a market situation, like the spa). In a liberal-democratic polity like the United States or the United Kingdom, a religious elected representative has a dual task: to be frank with constituents and colleagues about his convictions and the commitments of his faith, and to render his religiously informed conclusions in neutral terms when the time comes to write legislation. The law may not be sectarian, though our reasons for supporting or opposing it may.

As the philosopher Charles Taylor has argued, “There are zones of a secular state in which the language used has to be neutral. But these do not include citizen deliberation, … or even deliberation in the legislature.” Coghlan bungled this entirely, demonstrating not so much care for his constituents as lack of care for his church. He is a paradigm of how not to bring religion to representative office in a pluralist society.

Sometimes, of course, the demands of our faith will mean giving up opportunities available to others. Sometimes fidelity comes with a cost. If Coghlan’s Catholicism had “direct relevance” in his life, for instance, he would have taken a stand against assisted dying. Would that have cost him his seat? Maybe, or maybe not. But the final story I’ll share strikes me as a case where we do find a clear boundary for religion in public, but—crucially—a boundary religion should set for itself.

This is the story of Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who came to national attention in 2015 for her refusal to marry gay couples in the aftermath of the Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage, Obergefell v. Hodges. That refusal cost her six days in jail and hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal bills and damages. Davis is back in the news this month after asking the Supreme Court to revisit Obergefell, claiming the consequences she suffered violated her First Amendment right to free exercise of religion.

Davis has rarely been presented as a sympathetic figure, with critics citing her history of divorce and remarriage to mock her as a hypocritical, fundamentalist yokel. But surely it’s not so difficult to understand her perspective: In literally a single day, her career of 24 years went from being morally positive or neutral to necessarily complicit in grave sin.

Davis could be wrong, of course, about whether gay marriage is sinful. But that doesn’t negate the fact that her whole life changed in a matter of hours. Her situation is something like that of a career soldier being deployed to a surprise attack he believes to be unnecessary, aggressive, even evil in the eyes of God. He too might be wrong, and perhaps he should’ve anticipated this scenario before enlisting, just as Davis might have guessed that gay marriage would eventually be legalized and preemptively chosen another line of work. Yet none of that diminishes the dilemma when it comes.

This kind of dilemma could pop up in any line of work, but in state roles defined by law and ultimately answerable to the courts, the choice is apt to be particularly stark. In a way, that makes it simpler: If the ethics of your faith won’t let you do the job as legally required, well, then at least until the law changes, it can’t be your job. For Davis and our hypothetical soldier alike, the right answer—the faithful answer—is resignation. Maybe advocacy for a better law too, but first, resignation.

For Christians, this is not a new idea. Writing around 200 A.D., the theologian Tertullian argued that we are called by Christ to peace and therefore must not “make an occupation of the sword” or “take part in the battle” or “apply the chain, and the prison, and the torture, and the punishment.” If you are a Christian who works for Caesar, he said, “you are still the soldier and the servant of another; and if of two masters, of God and Caesar: but assuredly then not of Caesar, when you owe yourself to God, as having higher claims, I should think, even in matters in which both have an interest.”Quitting a stable government job over a pastime wouldn’t make much sense. But quitting because you owe yourself to God—because you understand yourself to be obeying the creator of all that exists, heeding the source of all goodness and truth, following the way of Love himself—that makes sense. It might be misinformed, but it’s not incoherent. It’s faith freely exercised, neither grasping for undue power nor ushered out of the public square.

Jonah Goldberg: In Defense of Thoughts and Prayers

“Though it’s not a faith or religion piece per se, this short standalone article from Jonah Goldberg this week certainly touches on a topic important to many people of faith. Following Wednesday’s deadly shooting at Annunciation Catholic School in Minneapolis, a handful of pundits and politicians derided the ‘thoughts and prayers’ condolences many people express publicly. Such denunciations are a mistake, Jonah writes:

The fundamental problem with condemning ‘thoughts and prayers’ is that it tries to snuff out a basic decency and skip straight to a policy argument. It suggests that people cannot show the most minimal kindness and expression of social solidarity to their fellow citizens unless they agree with their preferred policies.

Again, my point here is not to debate the merits of any particular policy proposal. On that front, the details matter—and so does the Constitution. But it is not clear to me that hectoring and shaming people who offer their thoughts and prayers in heartfelt sympathy gets the hectorers and shamers one inch closer to their preferred outcome.

Indeed, one could argue the reverse. If you’ve known someone with cancer, the first step toward wanting to mobilize for cancer research might start with the basic expressions of sympathy and empathy. That opens the door for the next steps. Asking them, ‘Is there anything I can do?’ Telling them, ‘I’m here for you.’ And, finally, if a political agenda is your goal, organizing for some larger cause.

It’s not clear to me that the same does not hold for victims of mass shootings or the public policies that might better combat them. Telling someone to shut up doesn’t win an argument. Shaming someone for caring doesn’t increase the amount of concern for our fellow citizens. Contempt only breeds more contempt.”

More Sunday Reads

- For Forward, Benyamin Cohen writes about the only synagogue designed by famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Beth Sholom in Pennsylvania is a design marvel, Cohen writes, but it’s also a dynamic and growing congregation. “Beth Sholom didn’t begin with blueprints. It began with a letter. In the early 1950s, Rabbi Mortimer Cohen — just 5-foot-3, but full of big ideas — reached out to America’s most famous architect. Wright was in his 80s, still working, and famously selective. He had turned down other synagogues before. But something about Cohen’s pitch captured his attention. Cohen wasn’t just asking for a building. He was asking for a vision: a sanctuary that would feel unmistakably Jewish and unmistakably American. A space that would root ancient tradition in modern form. A synagogue that would make people look up — and feel something. Wright said yes. In their letters, Wright described their unlikely collaboration as that of ‘congenial workers in the vineyard of the Lord.’ A plaque at the entrance still honors the partnership: Conceived by Rabbi Mortimer J. Cohen. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. It was one of the only times Wright ever shared formal design credit — and the only time he ever did so with a rabbi. They set out to design a building that could hold a people’s past and project its future. Wright’s design rejected every familiar cue: no columns, no arches, no stained glass depictions of Jewish life. Though a Unitarian, Wright immersed himself in Jewish tradition, working symbolic details into nearly every design element.”

- As the Minneapolis community continues to grieve this week’s tragedy at Annunciation Catholic School, the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis will continue attending to the spiritual needs of congregants and the community. That includes determining whether the mass shooting taking place inside a church constitutes the desecration of a sacred place under Canon law. Earlier this week, The Pillar explained what that means and the course of action Archbishop Bernard Hebda may deem appropriate. “And given the violence committed against school children and other parishioners there, it seems likely that Hebda will make use of the rite for a ‘public prayer after the desecration of a church,’ especially because the Ceremonial of Bishops specifically calls for its use in light of ‘serious offenses against the dignity of the person’ — which would seem necessarily to include shooting indiscriminately at persons. Of course, the Minnesota shooter’s motives continue to emerge — and seem to involve explicitly anti-Christian sentiment — but determining whether a church was desecrated does not depend necessarily on the motives of a person who committed a serious crime in the church.” The explainer continues: “The Ceremonial of Bishops explains that ‘reparation for the desecration of a church is to be carried out with a penitential rite celebrated as soon as possible. Until that time neither the Eucharist nor any other sacrament or rite is to be celebrated in the church.’ The rubrics indicate an important community role [in] the penitential rite. ‘It is fitting that the bishop of the diocese preside at the rite of reparation,’ the ceremonial explains. ‘This will demonstrate that not only the immediate community but the entire diocesan Church joins in the rite and is ready for repentance and conversion.’ Of course, that does not necessarily mean that the entire community is responsible for the desecration of the church. Instead, it means the whole community is invited to invoke Christ’s mercy over the harm of the desecration, to join with Christ in penance, as a participation in the cross. When the rite takes place, the altar is stripped bare, without altar cloth or candles, and other ‘customary signs of joy and gladness’ — like flowers or decorations — are removed.”

More Sunday Reads

For the Seforimchatter podcast last week, historian Melissa Klapper detailed the life of Emma Mordecai, an observant Jew who owned slaves, supported the Confederacy, and spent her entire life in the South. Klapper coauthored a book, The Civil War Diary of Emma Mordecai, that brings the woman’s wartime writings to life. Klapper’s conversation with podcast host Nachi Weinstein is fascinating.

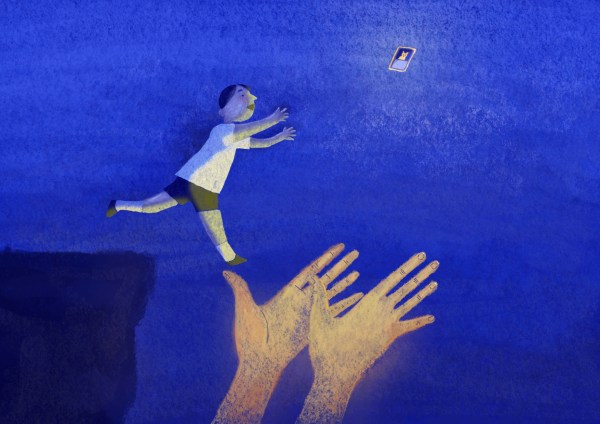

Religion in an Image

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.