Hi and happy Sunday.

Why, seven years ago, did a group of teens film and laugh as a man drowned to death in front of them, instead of helping him? Why do any of us make decisions in our own self-interest at the expense of caring for or serving those around us? Such questions are universal and timeless, to be sure. But in this week’s essay, Kevin Brown—president of Asbury University in Kentucky—deeply considers an answer that, he argues, secular moral philosophers of the West often miss.

Moral formation happens when we’re rooted in community, he writes, not in an understanding of abstract principles.

Kevin Brown: Real Virtue Has Roots

In 2018, 31-year-old Jamel Dunn tragically drowned in a Florida retention pond. Physically disabled and potentially disoriented at the time, Dunn waded into the water but struggled to stay afloat. The story drew national attention because as Dunn was thrashing in the pond, five teenagers were present who could have saved his life, but instead chose to laugh, taunt, and even film Dunn’s fight for survival.

Authorities did not charge the teens with a crime, because “there is no Florida law that requires a person to provide emergency assistance under the facts of this case.” Their (in)action was morally reprehensible, but not necessarily illegal.

Dunn’s tragedy has parallels to a famous thought experiment presented by controversial philosopher Peter Singer. In his 1972 essay “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” Singer asks readers to imagine approaching a pond where a child is drowning. Jumping in to save the child will likely damage or even ruin one’s clothes or shoes, but such inconveniences pale in comparison to the cost of not saving a life.

Risking your outfit to save a drowning child seems obvious and uncontroversial, but, says Singer, there is a principle in this thought experiment that has significant implications. If we are willing to have less to save a life in front of us, we should also be willing to have less to save a life across the globe. “If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance,” writes Singer, “then we ought, morally, to do it.”

The logic is clear and uncompromising. If the child in the pond demands our moral obligation, so does the “Bengali … ten thousand miles away.” Instead of spending money on frivolous enjoyments—such as from Starbucks, Netflix, or Amazon—Singer argues that the utility of discretionary income is maximized when spent on life-saving medicines or poverty reduction efforts in low-income countries.

It is a demanding theory. Singer is, in essence, suggesting that trivial consumer spending is morally equivalent to the derelict teenagers who idled as Jamel Dunn drowned. The theory requires that moral agents act in a rigorously impartial manner, prioritizing distant needs above our own everyday desires.

There is much to commend in Singer’s radical altruism, but something seems amiss. Moral obligations cannot be reduced to reason alone. Rational reflection can lead us to a principle or a standard, but the virtuous life requires a story.

The demands of morality.

Forgoing a latte to save a child’s life may seem logically defensible, but what, ultimately, can logic demand from us?

Singer’s universal moral principles are derived rationally, meaning they are not context dependent. Further, his rationality is decidedly utilitarian: The rightness of an action is determined by the net effect of its consequences, not because it conforms to a moral rule. The same dollar we may use on entertainment yields greater social impact when spent in service of, say, global health. Utilitarian reasoning, therefore, warrants that our income go to the latter.

On its face, this makes sense. Morality often has a radical character. Doing what is right can be accompanied by inconvenience, uncertainty, or loss. From an early age, we are told that we should “do the right thing” even when it costs us something—maybe everything. But Singer’s universalism is also thinly constituted—it tells us what we ought to do, but not how we become the kind of people who will do it.

To understand this limitation, we can contrast it with a thickly constituted framework—one shaped by narrative, community, and identity—that more closely mirrors a Christian moral understanding.

Like Singer, the Christian tradition also appeals to universal rules: the Ten Commandments, the Golden Rule, the Sermon on the Mount. Christians have long said that regardless of time, space, or place, there are just some things that are morally right.

But there is an important modifier for people of faith. Christians believe a moral reality characterizes our world in the same way a physical reality does—but moral vision and habits of virtue are learned and fostered in embedded, story-formed contexts.

While belief is at the heart of Christianity, we cannot reduce the faith to a set of propositions we are supposed to believe. Faithfulness, writes theologian Stanley Hauerwas in The Character of Virtue, is more constitutive of our Christianity than faith. In other words, it is not simply what we believe, but the interdependence of belief, action, and discipleship—the habituated embodiment of Christ’s character—that defines Christian life.

These beliefs and practices are adopted, internalized, and practiced in a social milieu of language, tradition, history, and place, as well as mediating institutions like families, churches, and schools. In short, a virtuous life is formed—not merely reasoned.

This is better understood by what New York Times columnist David Brooks describes as a “moral ecology” in The Second Mountain—cultural scaffolding that develops our moral vocabulary, orders our loves, grounds our identity, and channels these sensibilities into coherent actions. And it is fundamentally relational. As theologian James K.A. Smith writes, it includes “parents and teachers and aunts and uncles and priests and rabbis who walk with us on the road to character.” Moral education spans across “dinner tables, in classrooms, on football fields, in synagogues and churches.”

A moral life is a rooted life.

The ethics of obligations.

A striking example of moral conviction emerging from a moral ecology is found in the life of Simone Weil, the 20th century French philosopher and Christian.

In line with Western liberal democracies, Weil was a strong proponent of universal rights. But unlike most, she believed the legitimacy of rights comes from relational commitments—not Enlightenment rationality. “The notion of obligations comes before that of rights, which is subordinate and relative to the former,” writes Weil in her famous book The Need for Roots. “A right is not effectual by itself, but only in relation to the obligation to which it corresponds.”

In other words, rights do not exist independent of our day-to-day particularities. Rights follow obligations, and obligations emerge from rootedness—a thickly constituted network of relationships, community, and tradition. As philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre puts it, to know what to do, we must know who we are. And to know who we are, we must know the story of which we are a part.

Weil’s own death is a powerful example of this. Suffering from tuberculosis while exiled in England during World War II, she refused to eat more than what was rationed to her people in German-occupied France. Her self-imposed diet limitations had a significant impact on her health and ultimately led to her death at the age of 34. While the official cause was cardiac failure due to tuberculosis, the coroner added that it was accelerated by self-starvation: “The deceased did kill and slay herself by refusing to eat.”

This is radical. But Weil’s moral radicality did not emerge from an acontextual principle. She did not starve herself because of Kant’s Categorial Imperative or Hobbesian Contract Theory. Rather, her moral fortitude was a function of rootedness: her commitment to French identity, Christ’s self-emptying love, and Christian empathy for her compatriots.

Seldom do people sacrifice for abstract principles. But they will sacrifice—even die—for the people, places, and stories they belong to.

Rooted discipleship.

Consider the story of 16th century Dutch Anabaptist Dirk Willems, who was imprisoned for his faith. He managed to escape and was soon chased across a frozen body of water by one of the prison guards. While in pursuit, the ice broke beneath the guard, plunging him into the freezing water. Willems’ freedom was all but secured, but he chose to turn back and save his struggling captor. This was fortunate for the guard, but not for Willems, who was recaptured and burned at the stake.

What impels our moral responsibility to the stranger in need of rescue such as Jamel Dunn? Or, in the case of Dirk Willems, what motivates sacrifice—even to an enemy? Not the logic of a utilitarian maxim.

If we want a society where bystanders care for others—even at great cost—we cannot simply talk about stand-alone principles or universal rights; we must talk about obligations. And obligations emerge in moral ecosystems.

To be clear, contemporary Christianity has not been immune from the detached individuality or moral relativism of Western culture. But that is a departure—not an outworking—of the classical Christian vision of a rooted life organized around the story of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection.

To assert that Jesus rose from the dead and then qualify that as “a personal opinion” is, remarks Hauerwas, one of the stupidest things a Christian can say. If Christ resurrected, this changes everything. All the maps have been redrawn. The world is upside down. Things are not as they seem.

The truth of this story demands, says the hymnist, “my soul, my life, my all.”

The Christian tradition has a word for this: discipleship. A call not merely to know what is right, but to become the kind of people who do the right thing. That is, both a desire for the good and the capacity to carry it out.

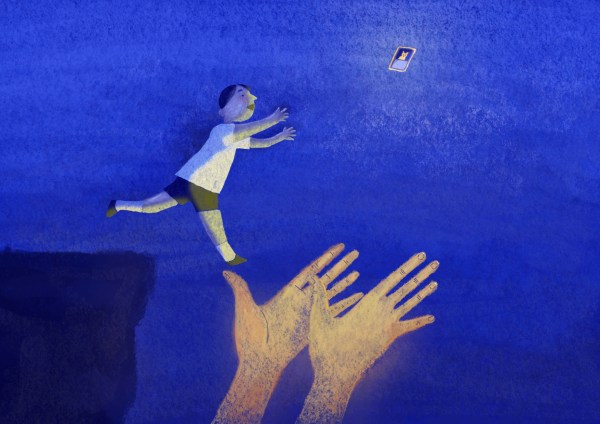

In a culture of weakening institutions and pervasive isolation, discipleship offers something deeper than thinly constituted reasoning—a story that shapes our moral imagination and directs our lives toward others. To be the kind of people who run toward those drowning, literally and figuratively, we need something beyond a universal precept or an ethics lecture.

It is our day-to-day roots, not abstract reason, that will cultivate the virtuous life and our moral concern for others.

More Sunday Reads

- In a lovely bit of reporting from the Associated Press, Fiona Murphy profiles black churches in Brooklyn whose choirs may be dwindling in number but not in devotion. “On Sunday mornings in Brooklyn, nicknamed the borough of churches, the muffled sounds of choir singers, hand‑claps and Hammond organs can be heard from the sidewalks. The borough still has a church on nearly every block, but over the years, the number of people in the pews has thinned. Many church choirs in the heart of Brooklyn, however, have kept singing — despite boasting fewer singers than in years past as neighborhoods face gentrification and organized religious affiliation decreases. Standing in front of the gospel choir at Concord Baptist Church of Christ in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, Jessica Howard, 25, led the gospel standard ‘God Is’ on a Sunday in July. Dressed in a powder-pink floral dress, she called out lines naming God as ‘joy in sorrow’and ‘strength for tomorrow.’ Some choir members wiped away tears as the song stoked emotions from around the room. ‘As a Black Christian person, as a descendant of slaves, I think when I sing, I feel really connected to my ancestors,’ said Howard, who grew up in Virginia and now sings as a soloist at Concord, where she’s been a congregant for six years. ‘I really feel sometimes like it’s not just me singing, it’s my lineage singing.’”

- In parts of India, attacks on Catholics—including two recent attacks on nuns and priests—are becoming more frequent. For The Pillar, Luke Coppen has a helpful explainer detailing the group behind some of these attacks—the Bajrang Dal—and its historical ties to a century-old Hindu nationalist movement. “The Bajrang Dal targets Catholics because of its broader hostility to religions that do not originate in India. Around 14% of Indians are Muslim, while just 2% are Christian, so much of the group’s activities focus on Islam, which it presents as an alien force seeking to undermine Hindu identity. But the Bajrang Dal is also suspicious of Christians, believing that missionaries are intent on destroying the fabric of Hindu society, luring converts through offers of money, education, and healthcare. Although Christians have lived in India since the 1st century AD, the Bajrang Dal links the minority to British rule, portraying Christianity as a Western cultural imposition.”

Religion in an Image

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.