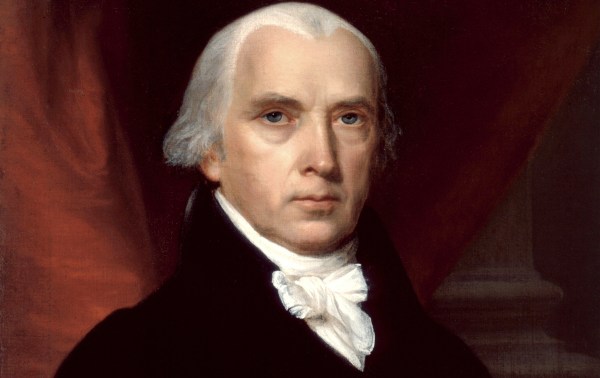

There are good reasons why the War of 1812 is largely a forgotten conflict; a cursory review of the war’s events reveals a slew of disasters for the infant republic—militarily, economically, and politically. The U.S. government entered the war with grand ambitions, but a deeply flawed strategy. President James Madison, Congress, and most of the public entertained dreams of seizing Canada and forcing Britain to change its policies of restricting neutral shipping and supporting violent Native American tribes. The nation’s collective expectation of how the war would go proved deeply flawed.

In the end, the invasion of Canada failed miserably, and the U.S. government couldn’t even defend its capital against invasion. The British emerged from the war having yielded nothing in their policies and with their Canadian territorial possessions intact. America abandoned all of its ambitions, while Britain yielded nothing, an outcome that would normally be seen as a clear-cut triumph for the latter.

And yet, the war ultimately worked to America’s advantage and Britain’s diminishment. The (much) weaker power had demonstrated that it was at least strong enough to inflict costs that the reigning hegemon was unwilling to accept. This reality would reverberate in American foreign policy for another century. The War of 1812 was enormously consequential for the fate of a continent, and it deserves a place of prominence in American history as the point at which ideas of “manifest destiny” became possible.

Causes of the war.

The causes of the War of 1812 stemmed primarily from geopolitical upheaval across the ocean. The French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte had destroyed the old order, and Britain was fighting a desperate war to prevent France from seizing complete dominance of the continent. Falling back on its traditional emphasis on sea power, the Royal Navy waged a costly blockade of Europe in an effort to strangle the French economy. While Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson solidified the Royal Navy’s status as an invincible force by effectively eliminating the combined French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar in 1805, maintaining a blockade demanded a massive number of ships and men. To keep their fleets manned, the British resorted to impressment—stopping merchant ships and seizing able-bodied seamen for indefinite naval service. While many sailors were genuinely patriotic, strict discipline and seemingly endless service drove high desertion rates, and many of the fleeing sailors ended up on American merchant ships. Britain’s response was to stop even neutral ships and search them for “deserters,” with some 6,000 native-born Americans drawn into the net and torn from their homes and families.

Even without impressment, relations between the new republic and its former mother country were strained. In the early years of the wars stemming from the French Revolution, the United States economy had been fattened by highly lucrative trade with both sides. That largely ended in Jefferson’s second term. France and Britain both tried to strangle the other’s economy by restricting neutral trade, and both were guilty of seizing American cargoes and restricting American access to European buyers. But as the side with complete dominance at sea, Britain proved the more egregious foe.

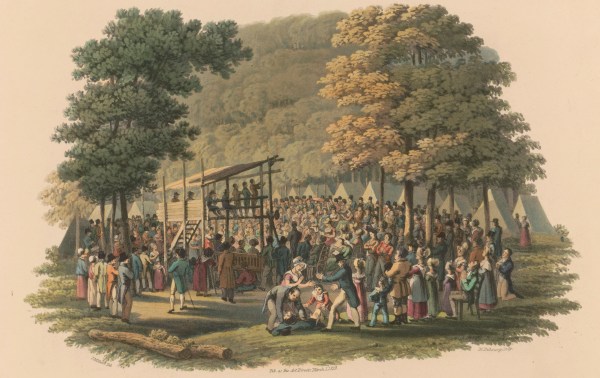

Finally, Britain continued to provide support to Indian tribes striking American settlements on the frontier. In this, Americans to some extent chose to target their outrage at Britain for supporting “savages” rather than acknowledge the real grievances that Native Americans felt over ever-expanding land seizures. Blaming Indian attacks on British perfidy offered a convenient scapegoat. There was, however, something to American complaints. For Britain, the loss of its 13 American colonies a generation before had not ended its ambitions in the New World, nor its desire to sustain a level of global hegemony that required keeping the United States, if technically independent, still decidedly subordinate. Humiliating episodes like the Chesapeake-Leopard affair, wherein the British Leopard opened fire on the USS Chesapeake off the coast of Virginia and seized a handful of deserters, reinforced the sense that Britain hoped for nothing less than to keep the United States a permanently minor power firmly in the orbit of the British Empire. Naturally, the more Britain could restrain American westward expansion, the easier this would be. Maintaining relations with Native American nations and supplying them with tools to resist American territorial expansion fit neatly into this ambition.

All of this fed into the rise of the American “War Hawks,” a younger generation in Congress who entered government eager for a chance to stand up to Britain and assert America’s total independence. British actions amounted to an attempt to force the United States to “subserve her interests as a colonial dependency” as one War Hawk put it. John C. Calhoun—the future firebrand of states’ rights but in his younger days an ardent nationalist—put it more bluntly: “If we submit,” to British bullying, then “the independence of this nation is lost.” Driven by this line of rhetoric and disgusted with Britain’s high-handedness, Congress formally declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812.

Surprise.

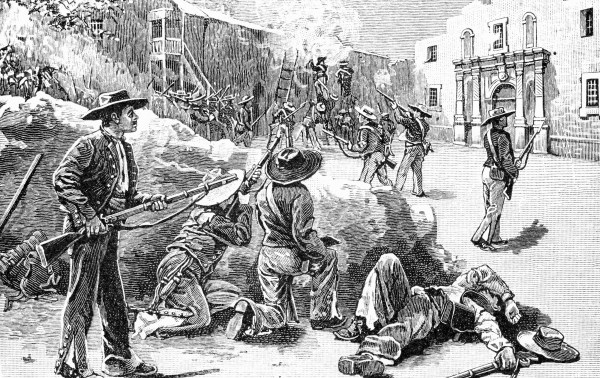

Americans entered the fight ill-prepared but convinced that, with Britain pouring all its resources into the fight against Napoleon, Canada would be easy pickings. Whether the United States would seize and keep Canada or use it as a bargaining chip for concessions on impressment and neutral trade was never entirely clear, and a successful invasion of Canada might have provoked an ugly fight among the War Hawks over the next steps. They never came close to confronting this issue, however. Fierce resistance from Canadians (and more than a little incompetence from aging Revolutionary War generals and half-hearted militiamen) shattered American illusions. Humiliating losses at Fort Dearborn, Detroit, and Chicago not only crushed dreams of Canadian conquest but left the American frontier open to a counterinvasion.

Dispelling the gloom from Canadian disasters, however, American frigates handed the vaunted Royal Navy a series of shocking defeats. Even most on the American side, including President James Madison himself, had entered the war assuming the Royal Navy would make short work of America’s fledgling Navy, and it came as a devastating blow when British ships lost, repeatedly. One British MP bemoaned that “the sacred spell of invincibility of the Royal navy was broken” by the losses. The Times of London conceded that “our navy was accustomed to hold the Americans in utter contempt,” a view that was badly shaken by the early successes of the U.S. Navy.

The War of 1812 was enormously consequential for the fate of a continent, and it deserves a place of prominence in American history as the point at which ideas of “manifest destiny” became possible.

America’s early naval victories proved a tremendous morale boost to the American public—and made celebrities out of a generation of American captains—but they masked serious difficulties that President Madison and his Cabinet conveniently ignored amid the heady celebrations. The Royal Navy might lament the loss of a few frigates, but it could easily replace them. The captures forced London to reallocate naval resources across the Atlantic, and once Britain increased its numbers off the Atlantic coast, victories would be harder to come by. Meanwhile, America’s primary strategy of attacking Canada was an abysmal failure and prompted worry about an invasion from the north.

Disaster.

And so the war took a dark turn for the United States in 1814. Britain shifted enough of its fleet to the Atlantic theater for an effective blockade, leading to the collapse of the American economy. Worse, Napoleon abdicated on April 6 of that year, freeing Britain to shift masses of seasoned veterans to America. The American war effort reached its nadir in August when British troops landed in Virginia, swept aside the militia troops in their way, and burned Washington, D.C., to the ground.

Amid such bleak developments, negotiators for both sides met in Ghent, Belgium, in August of 1814 to discuss an end to the conflict. The American contingent quickly dispensed with any pretensions of forcing Britain to give up impressment or make concessions on neutral trade. Flushed with recent successes, Britain’s ambassadors rolled out a set of demands that horrified their American counterparts. Britain wanted the United States to surrender territory in present-day Maine and Minnesota to Canada, and to designate a large portion of additional American lands as inviolable Indian territory. The Great Lakes must be cleared of all American naval vessels and fortifications, the British said, to be limited going forward only to British ships. Furthermore, Britain demanded explicit recognition of the Royal Navy’s right to control the seas and impress sailors from neutral ships. Appalled American envoys immediately rejected “conditions so injurious and degrading,” but they had little leverage other than outrage. Most of the American contingent considered breaking off talks and going home, but Henry Clay held out hope that Britain was bluffing. He prophesied that better terms would come, a hope that was contingent on the battlefield.

Stalemate.

Events turned back in America’s favor almost as soon as negotiations began. The British might have destroyed the capital, but they failed to crack Fort McHenry in the vital port city of Baltimore. The Royal Navy suffered a major setback on the Great Lakes when U.S. Navy Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough routed an enemy force on Lake Champlain, blunting a British invasion of New York. No less than the Duke of Wellington cited the loss of control of the Great Lakes as decisive. “That which appears to me to be wanting in America is not a general, or general officers and troops, but a naval superiority on the lakes,” he bluntly informed London, and without this, “I think you have no right, from the state of the war, to demand any concession of territory from America.”

The truth, even before Wellington’s assessment, was that Britain was tired of a war that served as a sideshow to seminal events in Europe, and, as Clay had foreseen, they were willing to cave on their terms to get it over with. Officially, the War of 1812 ended in a complete draw. The Treaty of Ghent set all territorial boundaries at status quo ante bellum, resetting borders to where they stood the day before the declaration of war. The final treaty also made no mention of high seas trade, impressment, or Indians. The two sides agreed upon nothing except that they would stop fighting.

Significance.

Had all hostilities truly ceased at that point, the perceptions of the war might have been different. But fighting did not actually stop until 19th century communications could get the word to every battlefield in the far-flung conflict. While the treaty was agreed upon in Ghent on Christmas Eve 1814 and ratified by both nations in February of 1815, the last naval engagement of the war happened in June. And most famously, Andrew Jackson’s ragtag force crushed a British invasion attempt at New Orleans after the treaty had already been signed. Jackson’s victory enabled Americans to collectively rewrite the narrative of the conflict. What had once been a slightly delusional attempt to seize a massive territory to the north and compel Britain to completely rewrite its foreign policy became lionized as a heroic effort that humbled “haughty Albion.” What was technically a draw on paper became, in American minds, a clear victory. There were obvious psychological reasons for remembering the conflict this way, but the perception was not entirely wrong.

For all its shortcomings, and there were many, America’s military establishment emerged far stronger than ever before. The Navy became a source of national acclaim, and the Army received levels of funding previously unthinkable. The coming decades would see marked advances in the capacities and professionalism of both branches of the American military.

America might still have been a second-rate power, but it was strong enough to deter Parliament from imposing Britain’s will on that side of the Atlantic. British hegemony on the North American continent was permanently in retreat after 1815.

For Britain, the War of 1812 was hastily swallowed up in obscurity thanks to Napoleon’s return to power and the subsequent Hundred Days campaign that culminated at Waterloo. This period of British history is remembered for toppling Bonaparte’s empire and establishing a peace that endured for the next century—the unfortunate spat with their American cousins is largely ignored, drawing scant attention even in naval histories of the period. Certainly, in light of the epochal events in Europe, it makes sense that fighting the United States to roughly a draw would fade in comparison.

A few British historians have stubbornly touted the war as a clear-cut victory for their side. The Americans, after all, failed to take Canada, failed to alter British policies on impressment and blockades, and failed to create enough of a distraction to undermine England’s war with Napoleon. They also failed to prevent their capital city from being burned to the ground. These are generally not the marks of a military triumph. The British government might have backed down from its more grandiose demands at the treaty negotiations, but it still achieved its most basic aims, safeguarding its North American possessions and its ability to conduct a global war.

What it lost is less immediately tangible, but no less significant. Neither side truly expected the War of 1812 to be the last Anglo-American clash, yet over the years, whenever controversy flared between Britain and its former colonies, successive British governments eschewed a fight. America might still have been a second-rate power, but it was strong enough to deter Parliament from imposing Britain’s will on that side of the Atlantic. British hegemony on the North American continent was permanently in retreat after 1815. “Superficially, the war seems to have been an inconsequential draw,” concedes Alan Taylor, but taking a “wider and deeper perspective reveals an ultimate American victory that secured continental predominance.”

Which meant that the war did have an indisputable loser: Native Americans. A retreating Britain never again proved to be any kind of ally, and the United States was free to pursue its vision of manifest destiny across the continent without interference. Over the next generation, various tribes and leaders attempted both accommodation and violent resistance, but with the same result. Indians were completely overwhelmed by the demographic wave that swept ever-westerward. Thus, even if the United States was repulsed in its attempt to take Canada and had to settle for its pre-war boundaries at the end of the war, it did ultimately gain territory from fighting Britain—it secured the ability to seize control of a continent.

Two centuries later, as the United States has replaced Britain as the globe’s preeminent power, Americans would do well to remember the War of 1812. Focusing on a strict dichotomy of “winning” and “losing” obscures the fact that hegemony can be fragile, and even seemingly successful campaigns can leave a nation with its ambitions thwarted. Britain struggled with projecting power across an ocean and juggling multiple threats in disparate theaters. These are starkly relevant issues to the 21st century United States. Whether Americans will have a better record of sustaining dominance remains to be seen.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.