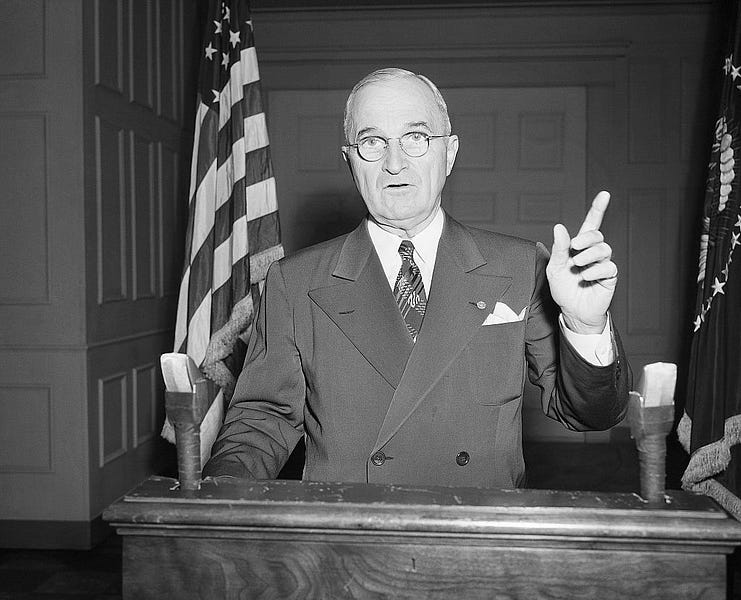

Seventy-five years ago today, October 5, 1947, Harry Truman gave the first televised presidential address from the White House. Truman spoke to the nation—or at least to the 44,000 American households that had TV sets at the time—about the continuing shortages in Europe following World War II and the need for Americans to conserve food to help the people of Europe. Another 40 million or so Americans had the capacity to hear—but not see—Truman via radio.

Truman’s speech was not the first time a president had appeared on TV, but address started a new and now familiar routine of the live televised speech to the nation: All of Truman’s White House addresses after that would be televised, and soon TV would eclipse radio as the way the Americans got their messages from the commander in chief.

The triumphs and missteps of the past 75 years have provided a playbook for Truman’s successors, one that could be useful for Joe Biden, whose biggest speeches have been too sharp and too partisan, especially for a president who was elected on the promise of uniting America. The lessons began with Truman’s successor. Dwight Eisenhower understood the importance of television, hosting the first televised presidential press conference, and even hired a well-known actor, Robert Montgomery, to help with his performances. When Ike was preparing to leave office in 1960, he and his speechwriters worked for months on a farewell address, the famed “military-industrial complex” speech, which imparted a warning he wanted to leave to the nation upon his departure.

Jack Kennedy was far better on TV than Eisenhower and recognized that TV was instrumental in his 1960 presidential victory. “We wouldn’t have had a prayer without that gadget,” he said after watching a tape of televised campaign appearances. He also was the first president to do his press conferences live and unedited on TV, where his quick wit had the reporters begging for more. Kennedy’s key televised address was his September 12, 1962, Rice University speech pledging to get America to the moon within a decade. This speech spoke to the aspirations of the American people and helped inspire a generation.

Lyndon Johnson was not nearly as good on TV as Kennedy, but he did know how to milk certain moments. His best-known televised speech was his March 31, 1968, speech in which he declared that he would not run for president again. His most impactful televised speech, however, was his voting rights speech, in which he went to Congress to argue for passage of the Voting Rights Act. He ended his speech with the words “we shall overcome,” bringing Martin Luther King Jr., who was watching it, to tears.

Richard Nixon’s best-known televised comment as president was probably the unfortunate “I am not a crook,” said to a group of newspaper editors at the Associated Press Managing Editors convention in Walt Disney World. He did, however, recognize that he was talking to a wider audience when he said it, prefacing the famous denial with the words, “I will say this to the television audience.” Nixon also had often unrecognized talent as a TV performer. His televised “Checkers” speech in 1952 saved his career at a time when Eisenhower was planning to drop him from the ticket over accusations of corruption. In 1968, he worked closely with a young producer on the Mike Douglas Show named Roger Ailes on a series of televised forums with voters that worked better for him than the standard podium-style speeches. And his May 8, 1972, televised speech on his conditions for peace in Vietnam was well-received, generating 40,000 mostly supportive telegrams and strong support in public opinion polls.

Gerald Ford gave a rare Sunday afternoon speech to announce his pardon of Nixon. While the pardon helped heal the nation after Watergate, it also was generally unpopular and contributed to Ford’s close 1976 election loss to Jimmy Carter. He in turn, was also partially done in by a televised speech, namely the July 15, 1979, malaise speech (in which he never actually used the word). It was Carter’s opponent in the Democratic primaries, Ted Kennedy, who gave the speech its appellation. The speech was initially popular, but then Carter followed with a Cabinet shakeup a few days later that went over poorly and reflected badly on the speech. The problem with Carter’s speech was not the unuttered word “malaise,” but its depressing tone, with the message that the American people were having a “crisis of confidence” that led to “the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.”

Carter lost to Ronald Reagan, who was as good at televised speeches as Carter was bad at them. Reagan used his experience and skill as a performer well as president. “He’s an actor,” one aide said of Reagan. “He’s used to being directed and produced. He stands where he is supposed to and delivers his lines, he reads beautifully, he knows how to wait for the applause line.” Reagan’s best-received Oval Office address to the nation was his January 28, 1986, speech following the Challenger explosion that killed seven astronauts, including the teacher Christa McAuliffe. It was put together on short notice on a day when the White House had been expecting to give the State of the Union address. The four-minute speech, drafted by Peggy Noonan, helped soothe the nation after a terrible tragedy.

Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, wasn’t nearly as talented as Reagan. His most famous TV appearance was probably his pledge, as a candidate, that he would not raise taxes under any circumstances: “Read my lips, no new taxes.” He later reneged on the pledge, severely damaging his reelection prospects. Bill Clinton was also unfortunate in that his most famous televised comment turned out not to be true. On January 26, 1998, as Washington was roiling over the revelations that Clinton had an affair with a White House intern, Clinton flatly—and falsely—told a televised audience that, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky.” The DNA sample on Lewinsky’s blue Gap dress proved him wrong and left a stain upon his presidency.

George W. Bush had multiple chances to address the nation after the 9/11 terror attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center, with mixed results. Bush initially rushed a post-9/11 speech from the Oval Office, which did not work, and was dubbed the “awful office” address. Bush later righted the ship with better performances in front of Congress and at Ground Zero. His impromptu Ground Zero remarks, said through a bullhorn while standing on the ruins of a firetruck—“I can hear you! The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon”—were probably his defining moment as president.

Barack Obama was probably the most gifted presidential speaker since Reagan. His terrific 2004 speech at the Democratic National Convention made his career. As president, though, he lacked a defining TV moment. His most memorable TV speech was probably his May 2, 2011, East Room speech to the nation in which he announced that U.S. forces had killed Osama Bin Laden.

Donald Trump loved the stage but was by no means a great orator. He could and did entertain crowds of supporters for hours at a time with his rally speeches, but they were more political than presidential. His great opportunity to appear presidential came during the early days of the coronavirus crisis in 2020. Unfortunately, his televised appearances during that period failed to meet the moment. First, his March 11, 2020 Oval Office address led to confusion rather than clarification. Then, his daily televised White House briefings attracted the captive audience of the socially distanced nation, but his misstatements, such as his suggestion that bleach could serve as a cure for coronavirus, made his appearances more of a political detriment than a benefit.

This brings us to Joe Biden. He has equated his political opponents with Bull Connor in a speech on voting rights, and last month called out “MAGA Republicans” in his “red sermon,” unfairly conflating those with pro-life views with election deniers. At this point in his presidency, it would behoove Biden to learn some key lessons from his predecessors on how best to be presidential on television.

From Ike, he can learn the importance of speaking only when he has something interesting or important to say. From Johnson, there is the understanding that the White House is generally the best venue for speaking and one should leave it only for very special circumstances, as with Johnson’s visit to Congress for his 1965 voting rights speech. Bush taught the importance of not being overly hasty with his rushed “awful office” address. Multiple presidents could have taught Biden the importance of not being partisan, as the best speeches over these 75 years could have been given by presidents of either party and do not mention party politics one way or the other. Finally, the best speaker of the bunch, Ronald Reagan, could have taught the importance of being brief. Biden’s “MAGA Republicans” speech was 24 minutes long. Reagan’s Challenger speech was only four minutes long, yet it is one of the best remembered speeches in presidential history.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.