When Donald Trump announced in mid-November of last year that he’d follow through with his promise to create a Department of Government Efficiency led by Elon Musk, I was both optimistic and skeptical. On the one hand, I work at a place with an entire website called “Downsizing the Federal Government,” so having a major new government project (and two of the world’s most attention-getting people) dedicated to the worthwhile—and increasingly urgent—cause of shrinking bureaucracy and cutting spending is an obviously good thing. (My Cato Institute colleagues even documented, in herculean fashion, all the things to cut in a December 2024 report.) On the other hand, there have been plenty of lame, superficial attempts to tame the federal Leviathan; serious spending reform is really hard and can’t just come from the president; and both lead characters—Musk being a quirky political neophyte and Trump being, well, Trump—have their flaws. So I’ve been hesitant to judge DOGE’s efforts without at least giving it a few months to get moving—especially given routine media hysteria about “draconian” cuts of, like, $12 of federal revenue and three federal jobs.

With Musk gone and DOGE’s future in doubt, now seems like a good time.

To be sure, DOGE isn’t dead yet, and some of its moves could take months to show up in the statistics. Nevertheless, Musk’s departure represents an important milestone—and perhaps turning point—that deserves an honest assessment of the good, bad, and ugly things DOGE has done so far.

Unfortunately, it seems to be more the latter two than the first.

The Good

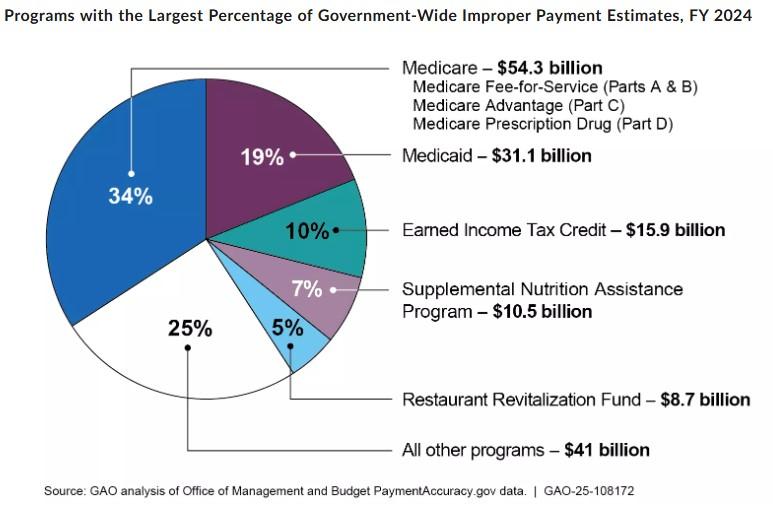

Perhaps DOGE’s greatest accomplishment was simply to focus the public on profligate government spending. As Cato’s DOGE report notes at the outset, “government debt, already historically high, is set to explode to unprecedented levels on policy autopilot over the next three decades, risking some combination of high inflation, slower growth, and federal default.” While much of this debt requires systemic reforms, it undeniably includes a massive amount of spending that’s wasteful by any reasonable definition. Cato’s Ryan Bourne reminds us, for example, that the famously sympathetic Government Accountability Office estimates that “the federal government loses between $233 billion and $521 billion annually” just to fraud. The same GAO report adds that since 2003 the government has made $2.8 trillion in “improper payments” (not necessarily fraud but erroneous in some way), but “the actual amount may be significantly higher” because the figure is based on only the “small number of programs” that are required to report such totals (itself a big problem!).

As my Cato colleague Chris Edwards—who’s been documenting federal spending problems since before many current Hill staffers were born—recently noted, there’s no “may be” about it:

The federal government is a vast transfer machine. It spends more than $4 trillion a year on 2,400 aid, benefit, and subsidy programs—from Social Security and Medicare to hundreds of lower-profile programs that members of Congress probably don’t even know they are funding. There is substantial fraud in nearly all the federal programs I’ve examined. People rip off the earned income credit, food stamps, housing tax credits, corporate subsidies, and many other programs. Medicare scammers rack up charges of more than $200 million before being caught.

Edwards points to a recent 60 Minutes episode on the scope of our government waste problem, in which the GAO’s own Linda Miller, along with “other fraud experts,” reckons that the actual amount of fraud in all federal programs may be twice what GAO reports. As a result, “We’re coming up close to the $1 trillion amount—is lost, every year, to fraud.”

$1 trillion. Every year.

There’s truly no shortage of examples of these problems—and of increasingly bipartisan recognition of them. In a recent National Bureau of Economic Research lecture, for example, the former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Joe Biden, Celia Rouse, estimated that the pandemic-era CARES Act alone generated more than $300 billion in outright fraud, including at least $64 billion in Paycheck Protection Program loans, $136 billion in Economic Injury Disaster Loans, and up to $135 billion in expanded unemployment insurance payments. “Waste and poor targeting” were also a problem: Economists estimated that PPP loans, for example, “cost between $169,000 and $258,000 per job-year saved, which is more than twice the average salary of these workers,” and—contra the program’s name—mainly benefited “business owners and shareholders rather than employees.”

A few months earlier, Cato’s Adam Michel dug into a Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) report, which found that over just six years the IRS had paid out $511 billion in fraudulent biofuels tax credits. The TIGTA report called the scam “one of the largest fraud schemes in US history” and attributed it to poor enforcement, onerous paperwork, and poor design (including “an unintentional loophole” that boosted the subsidy’s cost by 12 times). DOGE was perfectly right—and well in the mainstream—to take this stuff on, and as Bourne recently noted, it may have uncovered even “higher improper payment levels than people may have assumed” (e.g., millions in erroneous Social Security payments).

DOGE deserves similar credit for trying to improve antiquated government systems that help facilitate this waste. As Rouse documented in her lecture, the CARES Act also struggled because “federal data, computer, and human resource infrastructures were—and still are—not up to the task of delivering surgical and speedy support for the economy.” The IRS still uses decades-old computer systems (despite billions in past funding), and the Social Security Administration does too. The government-run U.S. air traffic control system, Capitolism detailed in 2023, was still using paper strips to track flights and remains a technological dinosaur today. The list goes on and on.

Third, and perhaps more controversially (at least in D.C.), DOGE was right to focus on the sprawling federal workforce and to treat federal employees more like their private sector, at-will counterparts instead of some special, protected class. As Cato’s DOGE report detailed, the 2.3 million executive branch civilian employees will receive an estimated $403 billion in 2025 compensation at an annual rate that’s more than 150 percent the average wages/benefits in the private sector ($157,000 vs. $94,000). Thanks to this pay and special legal protections, federal employees also quit and are fired much less often than private workers (including CEOs!), and they instead stay in their jobs for decades—at the risk of “creat[ing] a sclerotic culture infected with groupthink” and permitting, if not incentivizing, underperformance. The Cato report thus recommended not only reducing federal employment, but also making employee benefits, unionization rules, and hiring/firing/ accountability systems more like those in the private sector. DOGE didn’t do all those things, but it did at least try some of them.

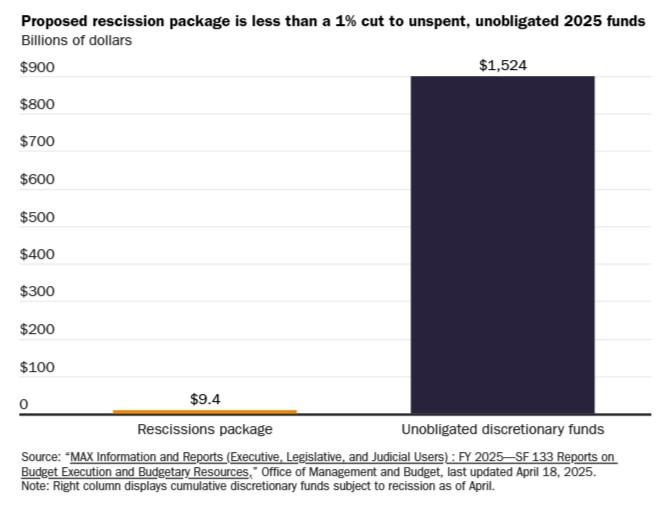

Finally, DOGE deserves credit for identifying some real government spending—and even entire programs (if not agencies)—that deserves to be cut and providing the impetus for both Trump and Congress to follow through. As my colleague Dominic Lett just documented, for example, the White House just sent to Congress a $9.4 billion dollar “rescissions” package to eliminate spending on foreign aid and cultural programs that are of dubious value or simply shouldn’t be done by government. Lett is right that this package is relatively small, but “every dollar saved helps and signals that Washington is working toward trimming excess fat from the federal budget.” Others agree that it’s a “step in the right direction to cut wasteful spending in the federal budget.” If DOGE and Trump make more moves like these, they’ll deserve more credit.

The Bad

The problem, of course, is that DOGE’s good intentions and discrete victories can’t be judged in a vacuum, and its bad mistakes are piling up.

For starters, Cato budget hawk Romina Boccia explains, Musk and company wildly underdelivered in terms of durable federal spending cuts (something even Musk himself now acknowledges):

Back in October, Elon Musk set the spending cut target at $2 trillion. That was quickly walked back to $1 trillion. Over the last few months, DOGE has had some modest successes, eliminating billions of dollars in government contracts and shrinking the federal workforce by about 12,000 personnel on net (closer to a 130,000 personnel cut in gross). At the same time, DOGE has suffered several major legal setbacks and self-imposed embarrassing blunders. The cumulative result? Elon lowered DOGE’s estimated savings again. This time down to $150 billion.

Unfortunately, even that $150 billion claim is optimistic. Itemized, verifiable cuts (those with receipts) sit at just $63 billion. Many of these receipts lack detail, contain errors, or otherwise have excessive savings claims that make the topline figure suspect. Per AEI’s Nat Malkus, accounting for clerical errors and inflated contract values roughly halves the claimed savings from contract elimination. The final tally of cuts could be slimmer when all is said and done.

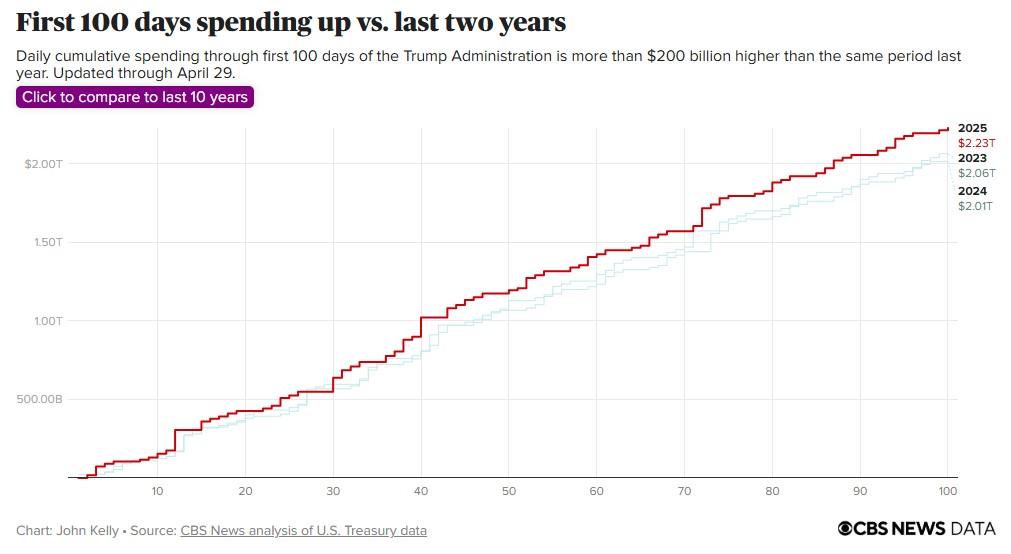

As of Boccia’s writing, in fact, federal outlays this year were about $135 billion higher than they were last year—“ironically close to the amount DOGE claims to have saved”—and $2-plus trillion annual deficits “are a foregone conclusion.” CBS News gives us the telling chart:

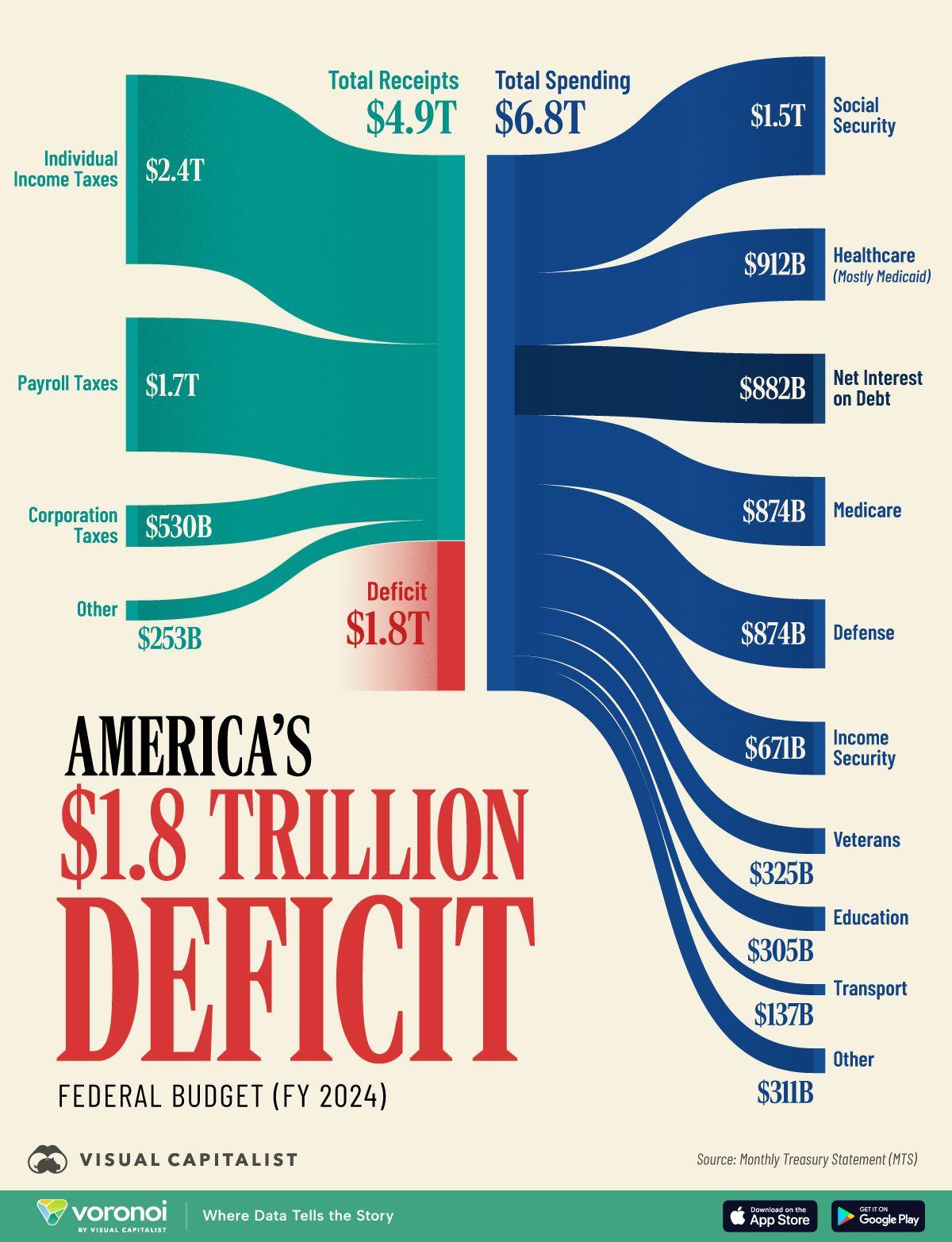

As Boccia goes on to explain, DOGE’s failure here stems from a basic fact that some in the administration seem to have ignored or failed to understand: Real spending reform requires Congress and, in particular, fixing U.S. entitlement programs that take up an ever-increasing share of the federal budget:

Relatedly, much of the government waste and fraud identified by various reports also requires congressional action because it’s hardwired into large U.S. spending programs designed by Congress. As Cato’s Michael Cannon notes, for example, the best way to reduce the billions in waste, fraud, and abuse in Medicare—one of the biggest fraud magnets—is to convert it into a Social Security-like cash-transfer program, which would “avoid scammers, eliminate wasteful expenditures, and punish high-price producers (including insurers)—because enrollees themselves will reap the savings.” More moderate approaches to eliminating Medicare waste and fraud require similar structural changes.

Such reforms aren’t something DOGE can do. They require Congress, as do other changes that would dramatically streamline government programs and reduce fraud (often by converting them to lump-sum cash payments instead of in-kind benefits).

Bigger, structural reforms—eliminating entire agencies, cutting vast swaths of the workforce—often need Congress, too. And, as Cato’s DOGE report helpfully reminds us, a major improvement in government waste can truly come from only a major reduction in the size and scope of government itself:

This problem is systemic and inherent to the government. Even the Government Accountability Office acknowledges that. It regularly documents extensive waste, fraud, and corruption across government programs and their poor results, even when they are relatively well implemented. In all these cases and more, real government efficiencies will only emerge from taxing less, regulating less, and doing less with an emphasis on supplying essential public goods at a low cost. Large parts of the government cannot be reformed. They must be eliminated.

That’s not to say that things like rescissions aren’t useful today, but the Trump administration’s DOGE-led efforts have thus far been much too timid. Indeed, as Lett shows, that $9 billion in rescissions is a tiny fraction of all unspent funds for 2025 and an even smaller share of this year’s $2 trillion deficit. There’s plenty more left to do.

The other obviously bad part of DOGE was its lack of thoughtful, transparent planning and the embarrassing execution of the plans DOGE did have. The Washington Post reports, for example, that “the Trump administration is scrambling to rehire many federal employees dismissed under DOGE’s staff-slashing initiatives after wiping out entire offices” and also trying to bring back “thousands of experienced senior staffers who are opting for a voluntary exit.” Because many former employees have moved on, however, certain key positions remain unfilled. Thousands of other people, meanwhile, “are returning in fits and starts as a conflicting patchwork of court decisions overturn some of Trump’s large-scale firings.”

As already noted, reducing the federal workforce is a laudable goal, and surely some of these “vital” government roles aren’t really so vital. But, like, maybe don’t start with mass firings at the agency managing our 5,000 nuclear warheads?

Then there’s DOGE’s widely ridiculed website, which “repeatedly posted error-filled data that inflated its success at saving taxpayer money” and, when confronted with those errors, simply eliminated any details that might make the numbers easy to check. (According to the Brookings Institution, about 40 percent of the DOGE website’s “wall of receipts” is inaccurate.) DOGE’s internal staffing decisions also, ahem, left much to be desired—including its being led by a guy with no government experience, several other full-time jobs, and, ahem, other proclivities.

Time and time again, DOGE showed a lack of forethought and planning about how to actually reform the government—disregarding the law and the longstanding advice of seasoned pros for a “move fast and break things” approach toward a sprawling, rigid entity full of people that, unlike in a private company and owed in large part to existing structural issues, don’t necessarily have to comply with the directives DOGE sent.

And it’s not like these things were novel or incomprehensible. Earlier this week, for example, the former comptroller general of the U.S. recommended a sensible plan for how DOGE should proceed with future cuts—a plan DOGE 1.0 obviously didn’t employ:

It’s critical that DOGE, in partnership with others, conduct a comprehensive review of the federal government—what it should do, who should do it, how it should be done and how to measure success. Such an effort could significantly reduce federal spending and increase government effectiveness. It should consider the federal government’s role as laid out in the Constitution, the statutory authorizations applicable to federal government departments and agencies, and the objectives that the federal government is attempting to achieve with the tools it has. The tools available to the federal government include direct spending, loans, government guarantees, tax preferences, regulatory matters and enforcement activities. The Office of Management and Budget and the GAO should then use the results of this effort to help the president and Congress discharge their respective responsibilities more effectively.

And, as Cato’s report laid out, it’s long been known that fixing government is actually much harder than fixing, say, a certain social media website:

President-elect Trump said that DOGE … “will become, potentially, ‘The Manhattan Project’ of our time,” but that understates the magnitude of the challenge. If reforming the federal government and reducing its burden on Americans were as simple as turning the theoretical insights of nuclear physics into a functional atomic bomb, it would have been done already. DOGE faces an even higher hurdle—the government itself. The government is a blunt instrument that tries to fix complex problems. By its very nature, it creates incentives for policymakers, public servants, and their cronies that all conspire against the allocation of scarce taxpayer resources to the production of the most highly valued public goods and, instead, channels them toward politically favored projects that shouldn’t be contemplated in the first place.

DOGE seemingly understood none of this.

The Ugly

If DOGE were just comically inept, it’d be one thing. But the ugliness comes from the ways that it might end up being worse than ineffective—and at a particularly perilous time for federal debt.

First, DOGE’s work could undermine future efforts to enact serious and durable reforms to the government and to get public buy-in for cuts that were bound to be controversial. As Boccia notes, for example, DOGE’s unilateral efforts run the risk of convincing large segments of the public that cutting “waste” can fix our debt, and that real, congressionally directed spending discipline isn’t needed—a misunderstanding that certain U.S. lawmakers and Trump administration officials are more than happy to play up.

DOGE’s strategy was similarly problematic. There are, for example, legitimate reasons to cut foreign aid, but leading off with cuts to a popular global AIDS program (PEPFAR) over tackling, say, corporate biofuels fraud makes no strategic sense—regardless of the merits of the programs being terminated. (And it looks particularly bad now those PEPFAR cuts are getting walked back.) Blindly firing people—including people that even we libertarians think should probably be employed by the federal government!—similarly ensured hostility among both the public and the federal workforce. And these concerns—some real and others imagined—were only amplified by DOGE’s lack of transparency and seeming disdain for the separation of powers and settled law.

Then there’s DOGE’s messaging. By wildly overpromising on cuts, it undermined its own results. (Eliminating $150 billion is nothing to sneeze at, but it seems insignificant when compared, as it always now is, to the $2 trillion Musk and DOGE originally promised.) By failing to explain in advance why various cuts were necessary or simply not catastrophic, DOGE ceded the field to opportunistic media and adversarial political groups, including powerful public sector unions. By never establishing clear goals or metrics for success, DOGE made it difficult for natural allies to back its efforts. And, as Cato’s Tad Dehaven explained, the appearance of DOGE incompetence—if not outright malice—was compounded by bizarre or even conspiratorial public claims, including Musk’s now-infamous “discovery” of Social Security fraud that “turned out to be previously known issues with government recordkeeping.” (This particular mistake also, Dehaven notes, feeds into the first problem above because “conceivably millions of Americans now incorrectly believe Social Security’s problem is fraud that the Trump administration can remedy.”

Cutting government projects and employees will always be messy, but DOGE’s approach seemed almost tailor-made to maximize conflict and minimize long-term results. Given the gravity of America’s fiscal crisis, DOGE’s efforts demanded surgical planning, clear messaging, and meticulous execution. Instead, we got endless chaos and culture war slop that might make future budget-cutting even more politically toxic than it already was. To really lean into my proud Gen X upbringing, government spending is the Death Star; we needed Star Wars but got Space Balls.

Will a better, future reform effort be derided and dismissed as simply “pulling a DOGE”?

Finally, there’s the risk that DOGE—far from cutting government—may be laying the foundation for its expansion. Some of these worries, Cato’s Gene Healy notes, are likely overwrought, but even he finds reason to worry that the Trump administration’s use of the impoundment “power grab” will become a way “to punish legislators who don’t fall into line” and “further accelerat[e] our slide toward one-man rule.” DOGE’s efforts to access Americans’ Social Security and IRS records—and to centralize personal data from various agencies—also raise real privacy concerns and fears that the data will be weaponized for illiberal policy goals (beyond the problematic immigration actions already happening). Those efforts could unfortunately last a lot longer than a few billion in rescissions—and, given some well-intentioned folks’ past cheerleading for DOGE, they might be accompanied by libertarian “endorsements” too.

That’d be really ugly.

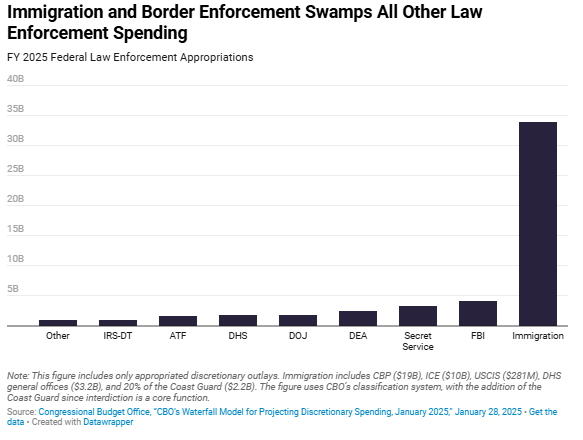

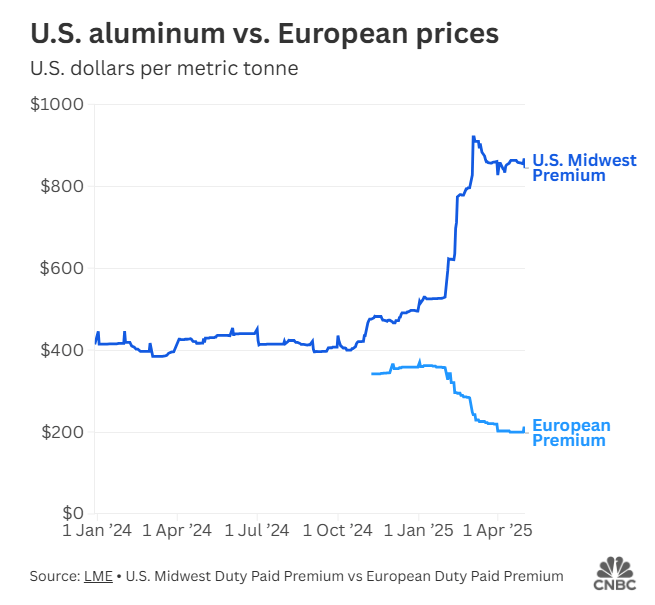

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.