(This article contains a major spoiler for Season 4 of Succession.)

“Politics is about who deserves to be more important,” political theorist Harvey Mansfield argued two decades ago. We are drawn to politics, classically understood (meaning not just elections, but even market and family dynamics), not just to distribute power, allocate resources, or even secure rights, but also because of what the ancients called thumos, “the part of the soul that makes us want to insist on our own importance.” Similarly, Hannah Arendt wrote in On Revolution that “freedom” in Greek political thought could be attained only through activities that “could appear and be real only when others saw them, judged them, remembered them.” “[The] life of a free man,” she observed, “needed the presence of others.”

This might be taken to portray politics as either anti-social or egotistical. This isn’t the case. Rather, Mansfield and Arendt recognized that politics depends on frequent human interactions. Politics pushes us away from others by inciting a desire to achieve greatness, but it also pulls us closer to others by making us want to be recognized as great. That paradoxical interplay helps us understand not only our politics, but also one of the most critically acclaimed television series in recent memory.

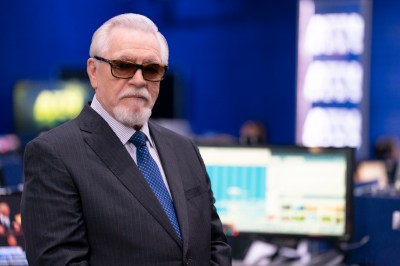

For four thumos-filled seasons, devoted fans of HBO’s Succession—which will air its series finale tomorrow—have watched the wealthy and influential Roys struggle over business deals, elections, familial tension, and more. Logan Roy (Brian Cox), the aging family patriarch, begins the series already having established his importance as the founder of the media conglomerate Waystar RoyCo, as well as its Fox News-esque media network, ATN. As his health worsens throughout the show, Logan resolves not to lose control of Waystar, while three of his children—Kendall, Shiv, and Roman—desperately try not only to make names for themselves, but to do so by taking control of the company in an attempt to finally win their father’s praise (and, more tragically, receive his love). The series has continually shown the Roys clashing with one another, craving to both excel and to be seen excelling.

This season of Succession surprised viewers with Logan’s untimely death, and most of its recent episodes have grappled with its aftermath. During last week’s penultimate episode, Logan received two contrasting eulogies grappling with his legacy: one from his brother Ewan and another from his son Kendall (Jeremy Strong). While Ewan describes Logan’s vices and the woe he unleashed by feeding the appetites of right-wing audiences (“He was mean, and he made but a mean estimation of the world”), Kendall reflects on Logan’s continual quest “to own and make and trade and profit and build and improve.” “Yes, he had a fierce ambition,” Kendall says, but “it was only that human thing. The will to be, and to be seen, and to do."

It’s easy during moments like those to hear echoes of the recognition-oriented politics described by Mansfield and Arendt. In a certain sense, Logan is an exemplar of it. His drive toward greatness pushed boundaries, and he fashioned a certain public space, with all the messiness and chaos that naturally follows when we bump up against one another. One could regard Waystar as even enabling human freedom, and interpret Kendall's praise of his father’s “will to be, and to be seen, and to do” as suggesting that Logan was a great force for good.

But the tragedy of Succession is that for all the greatness he achieved, Logan is a miserable man, and to the extent they try to emulate him, his children are deeply miserable too. Arendt again proves helpful in explaining why this is the case. Earlier in the same passage from On Revolution quoted above, she argued that tyrants, despots, and masters of the household are not truly free. If freedom requires a shared public life in order to be recognized by peers, then by seeking to lord oneself above all others, the tyrant deprives himself “of those peers in whose company he could have been free.” During a brief period this season when the Roy siblings planned to divest from the family business, rather than viciously compete over its leadership, they show true affection, loyalty, and love. But they ultimately sacrifice their familial bonds at the altar of self-aggrandizement in the contests of the public arena.

Succession presents a view of the greatness of ambition, but it also starkly reminds us that ambition alone cannot secure happiness absent other virtues. The Roys, driven by thumos, prize above all else their freedom to act in the world simply for the sake of acting in the world. The tragedy of Succession is not that its characters are ambitious or seek to be regarded as important, but rather that they lack any kind of transcendent commitments that can regulate their ambition or direct it to more noble purposes. The final episode remains to be seen, but the trajectory of Succession suggests that we’ll see the Roys’ desire for greatness folding on itself, inflating their egos and smothering their familial love in the process.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.