On the same day that violent Trump supporters took over the U.S. Capitol, a different kind of crisis was playing out on the other side of the world. Police in Hong Kong arrested more than 50 opposition activists and pro-democracy candidates, part of a pattern of mass arrests under China’s six-month-old national security law. The message couldn’t be any clearer: “One country, two systems” is over.

This type of insidious power grab has played out before. Haunted by the fall of the Soviet Union, Russian President Vladimir Putin has led his country on a political reconquista over the past two decades, emboldened at least in part by the United States’ unwillingness to show strength to a bully. It started at the turn of the century, when the Chechen Republic was brought under Moscow’s control. Following a period of increased ties between Georgia and the United States in 2008, Russia provoked a conflict in Georgia to justify a subsequent invasion. Perhaps heartened by the lack of international backlash, the Russians subsequently moved on Ukraine, claiming sovereignty over the Crimean Peninsula. This time, there were consequences—international sanctions were quickly slapped on Russia, and it was ejected from the G8. But while the Russian campaign of aggressive land-grabs was temporarily halted, no one believes it’s over.

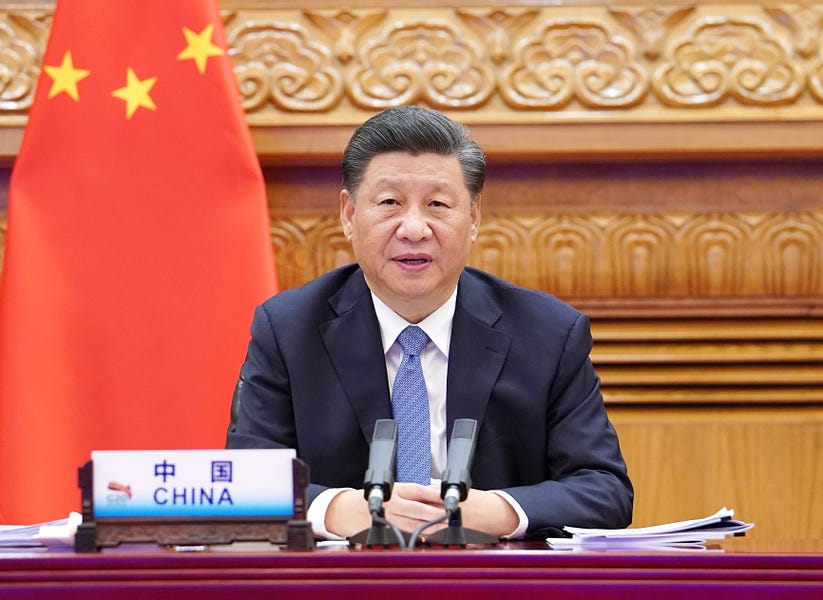

We now see the Communist Party of China (CCP) moving in a similar trajectory, but in a far more insidious way—emphasizing political rather than military strength, though not unwilling to resort to state violence. After consolidating its power for nearly two decades, China has taken advantage of the period of relative impunity afforded it by the Trump administration to launch a similar power grab in Hong Kong, to crack down in Tibet and engage in brutal repression in the province of Xinjiang. Today, Hong Kong has become subject to the most aggressive anti-democratic crackdown since the Tiananmen Square massacre. To this, the Trump administration said very little—and only on its way out the door did they take action to lift restrictions on diplomatic relations with Taiwan and to finally declare formally that genocide is occurring in Xinjiang.

What comes next, in the vacuum of U.S. leadership, is painted on the walls: Taiwan. Perhaps buoyed by its ability to act in Hong Kong—or emboldened by the lack of United States’ strength in international discourse following the Capitol insurrection—the CCP recently unveiled its detailed “reunification” strategy for Taiwan and has also been floating a “national reunification law” designed to bring the semi-independent territory to heel. In an effort to fend off Beijing, Taiwan has been working to deepen trade deals and strengthen diplomatic ties with the United States. It’s a move that has infuriated the CCP, which warned—following Pompeo’s lifting of diplomatic restrictions with Taiwan—that “The Chinese people’s resolve to defend our sovereignty and territorial integrity is unshakable and we will not permit any person or force to stop the process of China’s reunification.”

The CCP’s goal is clear, and the lesson for the United States—learned by witnessing Russia’s actions over the last two decades—is simple. Aggressive revisionist powers do not arrest their momentum of their own accord. The United States’ commitment to the independence of Taiwan has been upheld by every administration, and the Biden administration should be no different. Therefore, it is crucial to realize that defense of Taiwan doesn’t begin with just Taiwan: it begins here and now—in Hong Kong, in Xinjiang, and beyond—with a commitment to confront a pattern of unchecked aggression by the Chinese state.

Neither recent Democratic nor Republican administrations has proven capable of charting a path to mutual prosperity with China that doesn’t sacrifice more than it gains. The United States needs to decide where our priorities are—in the short and long term—and to devote our time, resources and capital to the outcomes we can realistically shape. One of our key priorities should be upholding our agreements and obligations to Taiwan—but in doing so, the United States should make sure that it understands core Chinese security threats and how to move around them in a way that does not provoke war.

America also needs to encourage the international community to engage. Together, like-minded democratic countries must strongly condemn and hand down consequences for this behavior before one incident turns into many, and the delicate balance of tensions in the region turns into a powder keg.

Tatyana Bolton is the policy director for R Street’s Cybersecurity & Emerging Threats team. She crafts and oversees the public policy strategy for the department with a focus on secure and competitive markets, data security and data privacy, and diversity in cybersecurity. Mary Brooks is a senior research associate on R Street’s Cybersecurity & Emerging Threats team. Her areas of focus include securing 5G and ICT infrastructure, technology and human rights, and how public audiences understand cyber power and security.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.