Clubhouse Is a Hit With Celebrities. Can It Be a Tool for Activists?

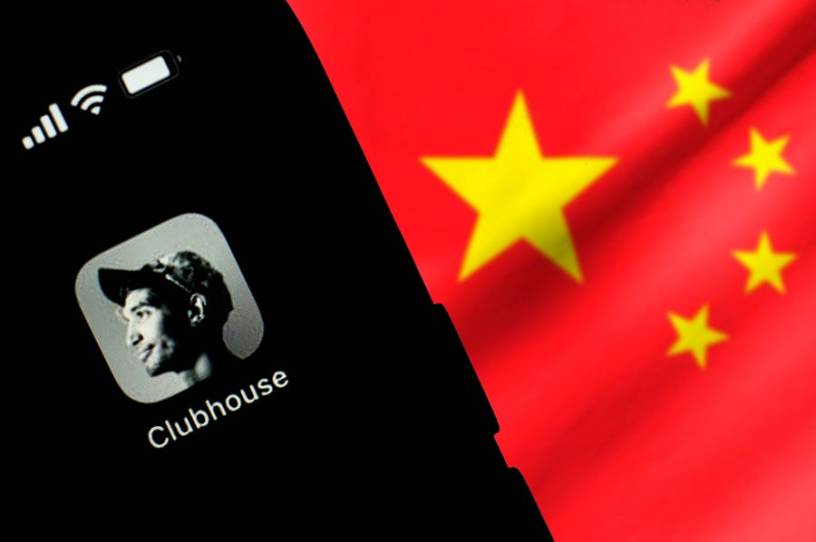

For a brief window at the beginning of this year, Mandarin speakers in mainland China and abroad used Clubhouse, a fast-emerging live audio app, to breach the Chinese government’s highly sophisticated censorship system. In forums that ran uninterrupted for days on end, Taiwan nationals, Tiananmen protesters, and Hong Kong democracy advocates formed connections with users living behind the Chinese Communist Party’s “Great Firewall.”

Within weeks of catching wind of the social network’s vast popularity in China, Beijing promptly barred users in the country from reaccessing their accounts. But the damage had been done. Thousands of young, tech-savvy listeners from China had already spent days absorbing the democratic values so deliberately stamped out by President Xi Jinping’s regime.

So what is Clubhouse and why is it a useful tool for activists combatting authoritarian cultures? Described as a “drop-in audio chat” on its pared-down website, Clubhouse is an emerging social media interface empowering users from around the world to engage and debate one another beyond the confines of 280 characters.

When you create an account, you’re presented with a slew of users, clubs, and chat rooms suited to an array of interests. There are conversation pages under categories like arts, wellness, faith, identity, world affairs, and “hanging out.” Some rooms are chaotic and intimate, while others include a moderator and carefully curated lineup of experts speaking on professional or technology-related topics.

A “raise your hand” feature allows members of the audience to voice their opinions, pending the host’s approval, and many of the more popular chats accumulate waitlists of tens to hundreds of people eager to chime in. The resulting conversations allow audience members to feel like they’re participating in their favorite podcast, undercutting the imagined authority gap between speaker and listener.

With its invite-only interface, Clubhouse enjoys an air of exclusivity despite amassing more than 5.3 million downloads in less than a year. Alpha Exploration Co., the parent company of Clubhouse that was founded by entrepreneurs Paul Davidson and Rohan Seth, launched in the spring of last year and quickly reached a valuation of $100 million with a user base of only 1500 after a few months.

The platform—now valued at $1 billion—recently gained traction via the social media megaphones of high-profile celebrity users like Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, comedians Kevin Hart and Tiffany Haddish, GOP political strategist Roger Stone, and musicians Drake and MC Hammer.

After a steady increase in usership throughout 2020—generated primarily by the platform’s adoption by high-profile musicians—Clubhouse rocketed to international prominence about two weeks ago, when Elon Musk went live with Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev after the GameStop controversy.

Musk interviewed Tenev for more than 20 minutes and quickly maxed out the chat room’s 5,000-person limit. Hundreds of thousands more watched the interview when it was uploaded to YouTube. Musk has been enticing new users ever since, tweeting about the platform to his 47 million followers and inviting ultra-famous public figures to chat.

Musk tweeted last Wednesday that he had arranged a Clubhouse interview with Kanye West. The longtime friends are both known for their eccentric online personas, and accordingly, “The most entertaining outcome is the most likely,” Musk ensured followers. The time and date of the interview have yet to be determined, but an emerging Clubhouse talk show—The Good Time Show—will act as host.

In a message directed at the Kremlin’s Twitter account, Musk also piloted the idea of a chat room featuring Russian President Vladimir Putin.

A follow-up tweet from Musk read “It would be a great honor to speak with you” in Russian. But his invite calls into question the ethics of offering up a platform to a prominent dictator, particularly one with a history of suppressing free expression and harassing the media on his own turf. In a call with reporters Monday, Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov called Musk’s bid “a very interesting proposal” and alluded to a possible collaboration.

Fortunately, the interface has propelled pro-democracy movements across the globe, bringing freedom of speech to regions where it’s typically lacking. Celebrity use of the platform brings Clubhouse awareness and new users, but its real value might be in helping dissidents living under totalitarian governments find their voice.

In one striking example, Turkish student activists and their supporters adopted Clubhouse as a platform for the free discourse often absent from the country’s traditional media. As Turkey’s young and educated elite takes to the app in droves, chat rooms about the Boğaziçi University protests have gained audiences of up to 5,000 people.

Large-scale demonstrations began early last month in opposition to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s appointment of ruling party loyalist Melih Bulu as rector of the prestigious Istanbul-based university. In the roughly 40 days since the movement began, more than 600 people have been detained across the country for their involvement—primarily in Turkey’s three largest cities of Istanbul, Ankara, and İzmir.

The two viral hashtags #BogaziciResist and #BogaziciSusmayacak quickly took hold on Clubhouse early this month, as Turkish speakers and listeners gathered in chat rooms to discuss the latest updates on the demonstrations. Some shared intel about those detained during the February 1 police raid on the university campus, while others debated the merits and motives behind the gatherings. Conversations are not archived, which offers participants at least a little protection from prying governments.

In China, the introduction of Clubhouse launched a scramble for information, as eager-to-learn young people joined the app en masse to have important cross-border conversations.

But when hot-button topics—like the Chinese Communist Party’s genocide in Xinjiang and massacre of demonstrators during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests—began to pick up traffic, Beijing’s monitors kicked in to bar users in China from reaccessing the platform. Reports of the block filtered into chat rooms in real-time, as participants voiced fears that they were experiencing their final moments of unobstructed speech.

While some mainland users can continue to access the platform using virtual private networks (VPNs) if they refrain from logging out or refreshing, Chinese participation has dwindled.

Zhou Fengsuo, a Chinese activist in exile best known for his leadership during the Tiananmen Square protests, participated in chat rooms before and after the block. The impact of new perspectives and open dialogue could be observed in real time.

“We discussed some very controversial topics. For example, who was responsible for the outcome of the Tiananmen protests,” Zhou, who landed the fifth spot on Beijing’s most wanted list for his role in the demonstrations, told The Dispatch. “There were people who were very new to this, but there were also people who participated in Tiananmen, people who participated in the 1989 pro-democratic movement in other parts of the country, and scholars who studied Tiananmen.”

“It was very stimulating to have all of these different perspectives together and to have an exchange of ideas with hundreds—and at one point about 1,000—participants, mostly young people,” he added. “Even just within the scope of a few hours, you could see the change of tune in people if they participated continuously.”

Not only does China restrict U.S.-based websites like Facebook, Instagram, and Google, but it also places strict constraints on traditional press. Beijing imprisoned at least 47 reporters in 2020 alone. Young people tend to be particularly susceptible to government propaganda, given severe limitations on speech in their lifetimes.

“If you go to China and you interview people, they always agree with the government whole-heartedly. All of the sudden we were seeing a different kind of people. They are still influenced by the government, they are still afraid, but you see their human side. We can just connect, heart to heart,” Zhou said of Clubhouse.

“It reminds me of Tiananmen Square, 32 years ago, where people physically gathered together could overcome their initial fear and encourage each other. There’s an amplifying effect when people gather together. They want to express themselves.”