One of the local radio stations began playing Christmas songs 24/7 sometime around Halloween. That’s a bit early for my taste, but who doesn’t like hearing some Christmas classics? Among the standards is Andy Williams’ old recording of “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year.” It’s a great song, but as Christmas bears down upon me, I must confess to having my doubts.

The mounds of papers and exams I have to grade at this time each year certainly don’t help. It is difficult to exaggerate the tedium of reading undergraduate essays year after year after year. Just this week I have been informed that St. Thomas Aquinas was born in 440 B.C. (a remarkable achievement, even for the angelic doctor); that “when people think of Oedipus they want to be just like him because they admire him” (someone please make certain that student is carrying no sharp objects); and that most immigrants, according to one leading scholar, are not coming here for the “free bees” (if you don’t get it, try reading it aloud, quickly).

It is not only the grading that leaves me questioning whether this is the most wonderful time of the year. It always seems to be the busiest time as well. We all bear our own crosses; one of mine is The Nutcracker. For almost 20 years now I have been watching my children dance in it, and every year, right when those final exams are staring me in the face, I spend two weeks driving—nightly—to practices, rehearsals, and performances.

And the bills! Presents, ingredients for the Christmas baking, food for the feast—In the words of Ebenezer Scrooge, “What’s Christmas time but a time for paying bills without money; a time for finding yourself a year older, and not an hour richer; a time for balancing your books and having every item in ‘em through a round dozen of months presented dead against you?”

To top it all off, I am just not very good at celebrating. I believe in celebrations in theory, but my practice falls short of the ideal. I am too much a creature of routine: I sit around the house not knowing what to do with myself and trying, with less success than my loved ones deserve, not to grumble. The real danger in grumbling, of course, is that at a certain point one risks turning from a grumbler into a mere grumble—“just the grumble itself going on forever like a machine,” as C. S. Lewis memorably puts it in The Great Divorce.

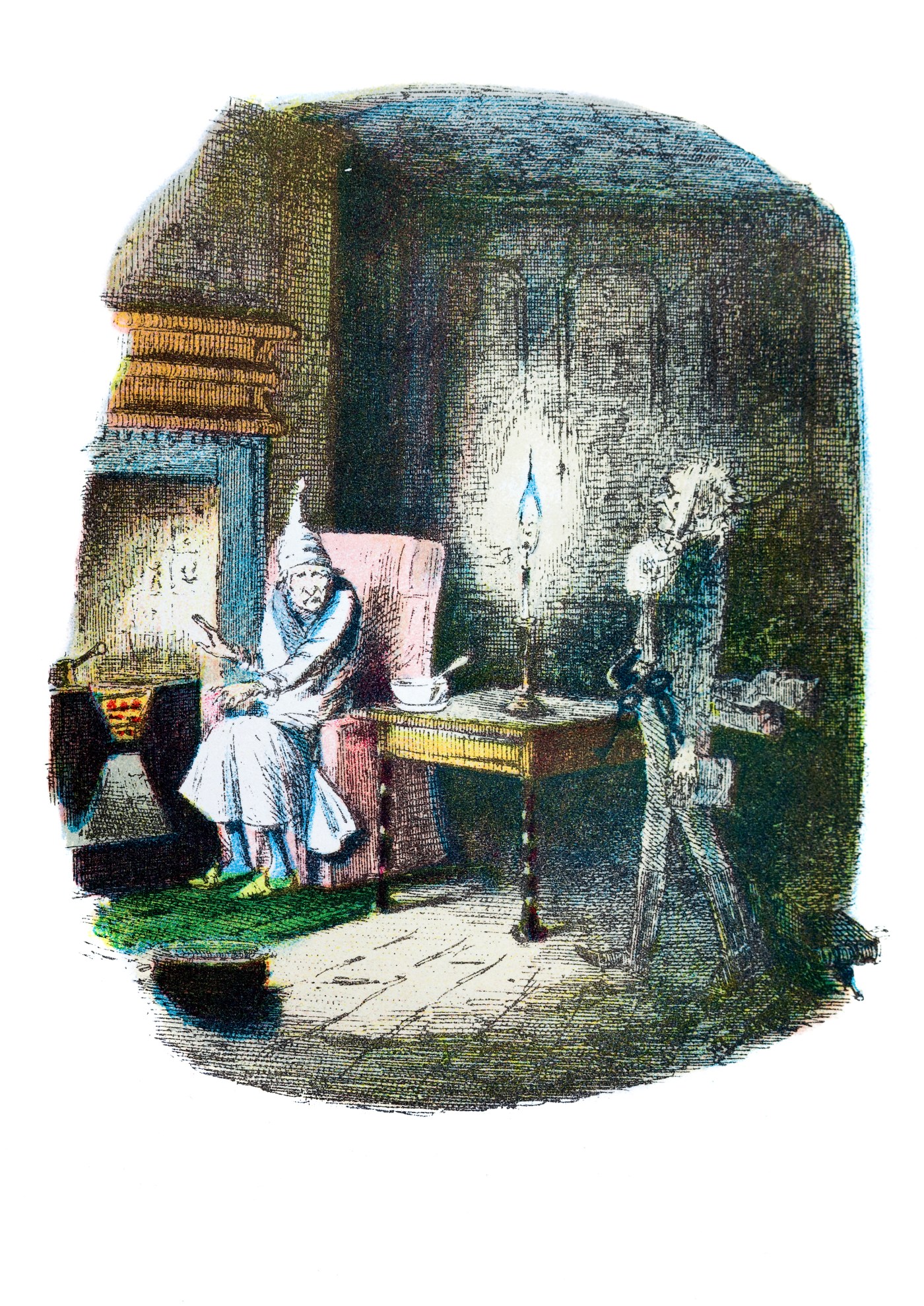

I am not yet, I hope, a mere grumble. But there is perhaps more than a bit of Ebenezer Scrooge in me. I find it hard not to feel at least a twinge of sympathy for the old man, put upon as he is by the boundless cheerfulness of his nephew and the more subdued good spirits of his clerk, Bob Cratchit. Fortunately, there are few better antidotes for one’s inner Scrooge than to re-read Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, as I have been doing again this Advent. Dickens manages to make even a bump on a log like me feel almost excited at the prospect of a dance or a feast.

He also manages to do two far more important things. On the one hand, he wonderfully portrays the long accumulation of actions and decisions that gradually turn one from a grumbler into a grumble. As Scrooge reviews his own past, present, and possible future, he begins to understand that his hardness of heart is not the inevitable consequence of a harsh and competitive world but is rather the product of his own habitual self-centeredness. Confronted by a dead man of business whose death is mourned by no one—but not yet realizing that he himself is that man—Scrooge recognizes that he alone has set himself upon such a trajectory. “I see the case of this unhappy man might be my own,” he tells the Ghost of Christmas Future. “My life tends that way, now.”

Dickens captures here a deep Aristotelian truth about the force of habit. But he is also, in a spirit perhaps more Christian than Aristotelian, an optimist about the possibility for reform. This is the second aspect of his book’s great achievement. As the same ghost leads Scrooge toward his own future gravestone and the crushing realization that, if nothing in his life changes, he himself will become that unmourned corpse, Scrooge pleads for assurance that he can avert that outcome. “Man’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead,” he admits. “But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me!”

There is hope for me, then—but only if I stop my grumbling. I have to let Dickens take me through Scrooge’s entire journey. If I join him early in the novel when he complains that Christmas is “a time for paying bills without money,” so too must I join his resolution at the book’s close: “I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year.” Only then can I share his gleeful discovery: “It’s Christmas Day! I haven’t missed it.” It won’t be easy. But I am up to it. Surely I am up to it?

I don’t suppose that anyone is ever likely to say of me, as they came to say of Scrooge, that “he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge.” But perhaps I can do a little better this year than last. And next year better still? In the hope that I might not only utter, but also be included in, the benediction of Tiny Tim: God bless us, every one!

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.