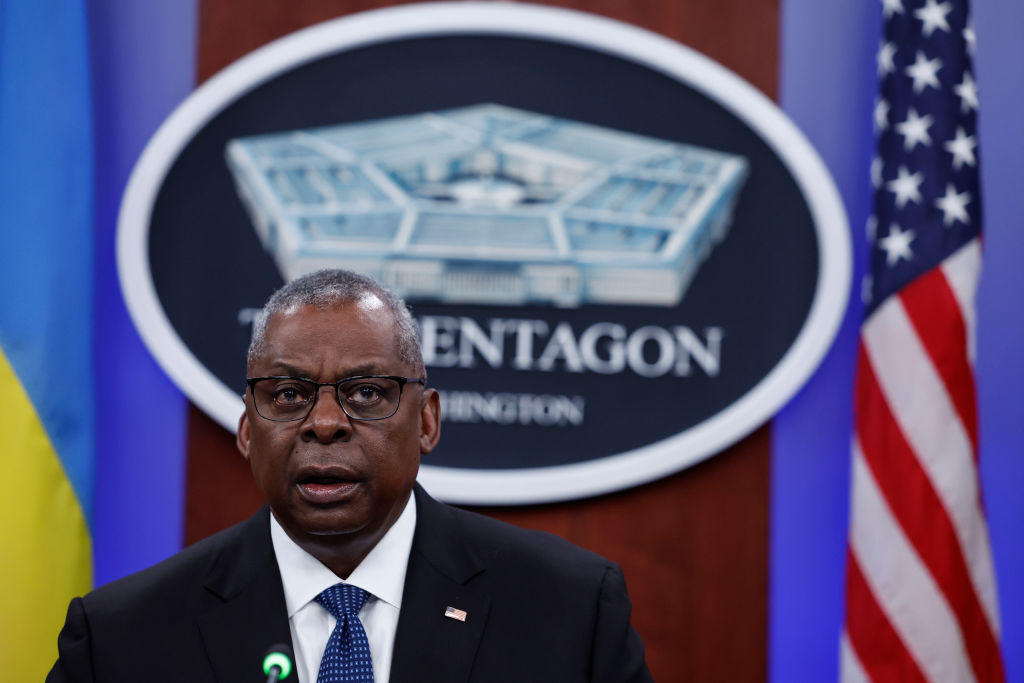

Beginning late on January 1, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin was hospitalized and in an intensive care unit, yet no one in the military chain of command seemed to know about it until January 5. Reporting about Austin’s recent hospitalization has moved on from “why” (complications following prostate surgery) to the familiar Washington cadence of “Who knew what, and when?”

Other questions about the military chain of command are also relevant: The secretary of defense plays a vital and singular role in executing the president’s national security directives. What happens if he’s not there to answer the phone?

What is the secretary of defense’s role in the chain of command?

Responsibilities for the secretary of defense are laid out in Title 10 of the U.S. Code. He is “the principal assistant to the President in all matters relating to the Department of Defense,” and “has authority, direction, and control over the Department of Defense.” The key words here are “assistant” and “control,” as they represent two distinctly different types of responsibilities.

The secretary of defense controls the Department of Defense in the way a CEO controls a business. This is often referred to as “man, train, and equip,” or some variation of that. The secretary sets policies and direction within the framework laid out by the president, overseeing a sprawling bureaucracy consisting of 3.4 million people across 160 countries and spending over $800 billion a year. His responsibilities in this role flow down through the three service secretaries of the Army, Navy, and Air Force to all the military and civilian bureaucracies that perform acquisition, accounting, planning, human resources, training, and other functions that most civilian managers would recognize. These operations move at a pace that makes glaciation look like greased lightning, so the secretary’s role in day-to-day operations could be considered less vital.

It is the secretary’s operational role as assistant and adviser to the president that raises more serious questions about whether Austin’s actions created a broken link in the chain of command.

Among other responsibilities, the secretary of defense may have to recommend to the president that people should die, then issue orders sending Americans out to kill them and possibly be killed in the process. These recommendations may be based on established and approved operational plans, quickly developed contingency plans in response to fast-moving events, or anything in between.

The four-star combatant commanders around the globe report directly to the secretary and execute orders relayed by him through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. This latter twist is an artifact of the Goldwater-Nichols Defense Act, which updated Title 10 joint chiefs functions to bring the services more into alignment and streamline the chain of command. The Joint Chiefs of Staff are the secretary of defense’s principal advisers for operational matters and provide him with the global perspective that individual combatant commanders may lack. The practical effect is that the joint chiefs act as a sort of gatekeeper for plans coming up from combatant commanders for the secretary’s approval, and as a facilitator for orders going down to the ranks from the secretary.

While policies implemented under Goldwater-Nichols place the Joint Chiefs of Staff firmly in the operational chain of events, they are not in the chain of command and could not issue orders without the secretary’s (or president’s) direction.

So when the proverbial 3 a.m. telephone call comes, the secretary of defense is the only one who can represent to the president the military’s best estimate of a given situation, then translate the president’s orders into military action.

What should have happened with Lloyd Austin’s case?

If the secretary is incapacitated or removed for whatever reason, the deputy secretary is able to perform all the role’s duties. “The Deputy Secretary shall act for, and exercise the powers of, the Secretary when the Secretary dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office,” Section 132 of Title 10 of the U.S. Code reads. The key word in this case is “unable.”

Austin’s condition throughout the time period in question isn’t yet clear from news reports, so it is not clear whether or for how long he was incapacitated. But that likely will come to light during a Defense Department’s inspector general investigation, announced Thursday.

One day after his hospitalization began, Austin did delegate at least some of his duties to Deputy Secretary Kathleen Hicks during this period, apparently without telling her why. But Pentagon press secretary Maj. Gen. Pat Ryder told CNN on Sunday that Austin had delegated only “certain operational responsibilities” to Hicks that are still unclear to the public. Austin did not notify the White House of his situation, so the president wouldn’t have known to call Hicks in the event of an emergency. Also unclear is whether Austin and Hicks coordinated and whether she could have provided current assessments and recommendations for the various U.S. military situations around the globe.

What will happen next?

Discovering the degree to which existing procedures were or were not adequate or followed seems to be next on the agenda. In addition to the Defense Department’s inspector general investigation, this week the secretary’s office indicated it will review how Austin handled his leave. Republicans have vowed to investigate as well.

There’s also a question of whether so-called “vacancies” laws were violated, under which executive departments must inform Congress and other entities of any coverage gaps in leadership positions. That’s more of a political question than a potential operational vulnerability, and will certainly be addressed in the recently announced investigations.

While Austin’s absence might not have disrupted the day-to-day operations of the Pentagon significantly, it’s important that these investigations address the tangible risk of severing a link in the military chain of command without anyone knowing about it until after the fact.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.