Like a lot of parents, I cried the first time I saw Inside Out, Pixar’s clever and amusing story about the emotions—Joy, Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness—within the brain of an 11-year-old girl named Riley. But rewatching the 2015 film recently, with a few more years of parenthood under my belt, I was struck by the disconnect between its prescient insights into parental worries and its old-school depiction of childhood.

On one hand, the original Inside Out explored a question that has since captivated large swaths of the parenting internet: How exactly are we supposed to deal with our kids’ feelings? On the other, its portrayal of 21st-century childhood felt like something from a bygone era. At one point Riley skips school and boards a cross-country bus by herself, only to reconsider and run back home through darkening city streets. Her parents only discover her missing when they return from work, apparently having assumed she’d been hanging around home alone after school like a latchkey kid from the 1980s. It all felt a little dated, especially given that the same year the film came out, the average American parent said kids under 12 shouldn’t stay home alone for even an hour.

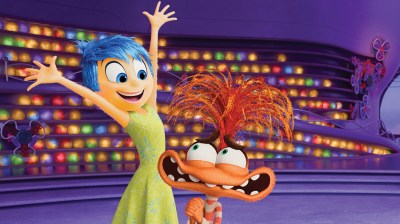

Inside Out 2, released earlier this month with comedian Amy Poehler reprising her voiceover role as Joy, feels similarly in and out of step with the times. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more timely topic than teen anxiety, which has become the subject of endless books and think pieces over the past few years and takes center stage in Pixar’s sequel. Like its predecessor, the new film grapples with the topic in a mostly creative and insightful manner—but it somewhat clumsily avoids acknowledging the Instagram-scrolling elephant in the corner.

Riley, now 13, begins the film thriving emotionally. We learn that certain memories, carefully chosen by Joy, have started to create beliefs (“I’m kind,” “Mom and Dad are proud of me,” and “I’m a winner”) that form the roots of Riley’s “sense of self.” Rendered in her mind as a glowing tree-like structure that occasionally repeats the mantra “I am a good person,” Riley’s positive self-identity functions sort of like her conscience, guiding her to make good choices.

All that is quickly complicated by the onset of puberty, which ushers in a much more sensitive emotional dashboard. Joy and the original crew must get along with a new crop of emotions, including Envy, Embarrassment, and Ennui. But the main new player is, of course, Anxiety (voiced by Maya Hawke), a chipper orange thing with bug eyes, a wide toothy grin, and a frazzled tuft of stringy hair.

Over in real life, Riley and her two best friends are heading off to a weekend hockey camp run by the local high school coach. Riley hopes they’ll all play together the following year, but on the drive out to camp her friends reveal they’ve been assigned to a different school. This will be their last weekend playing hockey as part of the same team.

You can probably guess at the basic contours of the story. Convinced that finding new friends at camp will make or break the next four years of Riley’s life, Anxiety steadily takes control, even going so far as to toss out the teen’s positive sense of self and banish Joy and the other original emotions from “headquarters” (i.e. the control center of Riley’s mind). Anxiety then sets out to construct a new sense of self for Riley, but one that is rooted in teen insecurity (ex: “If I’m good at hockey, I’ll have friends”). This leads Riley to make all sorts of poor decisions, from snubbing her friends, to fake laughing, to dying her hair red. Unsurprisingly, Anxiety’s plan ultimately backfires. (Reader beware: spoilers ahead.)

As the parent of a somewhat anxiety-prone daughter, I found the film’s depiction of childhood angst genuinely clarifying. My daughter and I have taken to anthropomorphizing her anxiety as a means of grappling with it. That said, we typically discuss it as something of a clueless imposter (we call it her “worry dragon”), a mostly unwelcome presence that would ideally go away. Inside Out 2, however, presents Anxiety as an ordinary emotion that means well and has a rightful place in our minds just like all the others. After Anxiety’s tyranny ends, the other emotions don’t boot her from headquarters but instead put her in her place—an armchair, where she drinks tea and serenely focuses on things she can control. It’s a subtle but useful distinction, especially given that TikTok-prompted self-diagnoses have made it far too easy to pathologize negative emotions.

The movie also gestures at the pitfalls of trying to maintain a selectively flattering self-image. By the time Riley’s Anxiety-shaped sense of self is complete, it is riddled with self-doubt. Joy manages to restore Riley’s original sense of self to headquarters, yet even that fails to quell the paralyzing whirlwind of angst that has taken over her mind. Only when Joy steps back and allows a more complicated self-image to flower from a broader pool of memories—with beliefs such as “I’m not good enough” and “I make mistakes” intermingling with those such as “I’m kind” and “I’m a good friend”—does Riley’s anxiety subside. The (subtly Christian) message seems to be that part of growing up is reckoning with our own brokenness. Shame, too, has its purpose.

Yet while the movie offers real insights into anxiety, it doesn’t quite capture modern-day American teenhood. That’s because for most of its runtime, Inside Out 2 largely ignores two of the major factors affecting teens today: Smartphones and social media.

The hockey coach conveniently confiscates her players’ phones at the start of camp, a move that doesn’t quite manage to account for their omission from a present-day film about adolescence and teen anxiety. There’s a scene in which Riley hangs out after practice with a handful of the camp’s older attendees, including with Val, the varsity captain and star player. When one of the older girls asks what sort of music she’s into, Riley mentions a band she actually likes—and is crestfallen to discover that it’s one the older girls consider somewhat passe, even childish.

I couldn’t escape the suspicion that this just wouldn’t happen. When they first meet early in the film, Riley reveals she idolizes Val: She knows everything from the older player’s hockey stats to her favorite color. Given how easy it is to casually stalk on Instagram or TikTok, how would Riley not have already known what sort of music Val liked?

The absence of phones is only more striking given the film’s focus on teen anxiety. Even if you aren’t totally sold on the idea that phones are a major cause of the recent youth mental health crisis, there’s simply no doubt they play a role in it. At the very least, confiscating the phones from the movie seems like a missed opportunity to explore how the phones serve as a conduit for anxiety. And I find it hard to believe that, even with Riley’s phone locked away, social media wouldn’t feature somewhere within the paranoid visions of future failure and social ostracization that Anxiety drums up in Riley’s imagination.

Maybe I’m being needlessly grumpy. Still, the decision to oust smartphones and social media from the movie’s depiction of American teenhood was clearly deliberate. Why, then, does Inside Out 2 choose to do so? The writer’s depiction of Ennui offers a clue: She’s a slothful character with a thick French accent who spends most of the movie slouched on a purple sofa, operating Riley’s emotions from an app on her smartphone. It’s only after her phone is mysteriously stolen that Ennui shows any emotion, leaping up from her spot, shouting, and searching for the device.

Perhaps the writers knew that with a smartphone in hand, an anxiety-riddled Riley would have spent the entire movie doom-scrolling. Whatever the reason, there’s something a little on the nose about the decision. Even on the big screen, managing the emotional turbulence of adolescence is easier when teens don’t have small screens in their hands.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.