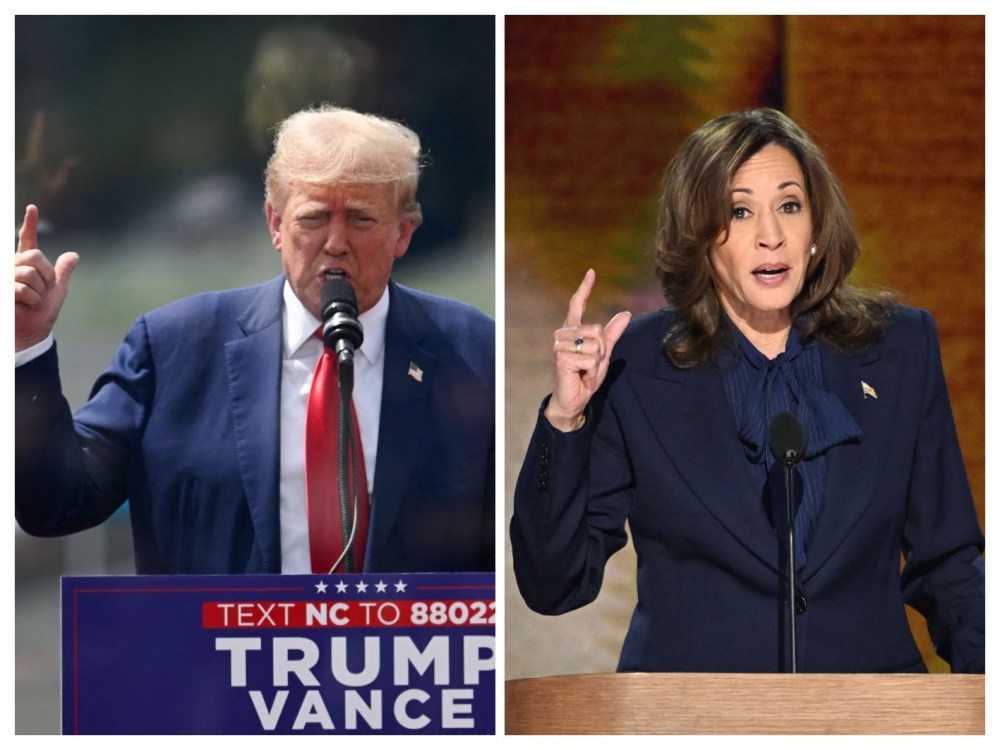

One presidential nominee recently vowed that their administration “will be great for women and their reproductive rights.” The other hopes to build the wall. Which is which?

Right. Donald Trump is the abortion warrior, Kamala Harris is the border hawk.

Let’s try an easier one. One nominee wants police to stop people on the street and confiscate their guns. The other pledges to “always ensure Israel has the ability to defend itself, because the people of Israel must never again face the horror that a terrorist organization called Hamas caused on Oct. 7.” Which is which?

Trump is the gun-grabber, Harris is the proud Zionist.

One more, and it’s a doozy. One campaign insists on taunting its opponent with juvenile insults while the other solemnly declares that “acting like whiny schoolchildren is not a political strategy.” Which is which?

Yes, really: Harris is the “mean tweets” candidate, Trump is the voice of—ahem—dignity.

Ten weeks from Election Day, this campaign has gotten very weird, and that’s not counting the fact that Trump is backed by the most prominent living Kennedy while Harris is (almost certainly) the preferred candidate of the House of Cheney. Even America’s political dynasties don’t know which way is up.

Earlier this month, I wrote about how the race has devolved into a show about nothing, but it might be more accurate to say that it’s a show in which the two leads are increasingly playing the same role. Trump is running as a big-spending, functionally pro-choice, tough-on-crime border enforcer. Whereas Harris is running as … a crime-fighting, border-enforcing, pro-choice, big spender.

Even the two candidates’ differences on foreign policy might not be as sharp as the parties’ respective bases would like to believe.

Presidential campaigns are supposed to be a slugfest. Instead, from the standpoint of policy, we have two fighters in a prolonged clinch. When Harris tries to break free to throw roundhouses about abortion, Trump grabs her and starts babbling about “reproductive rights.” When Trump shakes loose and rears back to hit her on immigration, she wraps him up with promises to “hire thousands more border agents and crack down on fentanyl and human trafficking.”

As much as I hate to credit populists with anything, their endless whining about the so-called “uniparty” that dominates Washington rings truer lately than usual.

The candidates are converging on policy—and they’re doing so, bizarrely, during an era of unusually bitter partisan polarization. If ever there were an election where the two nominees should be leagues apart with their respective agendas, one would think, this is it.

Why are Trump and Harris moving toward each other on policy?

Means, motive, and opportunity.

For the first time since the 2004 election, both nominees have strong reason to think they could lose.

Joe Biden led Trump comfortably in polling throughout the 2020 campaign. Hillary Clinton led him reliably, sometimes comfortably and sometimes less so, in 2016. Barack Obama got a post-convention polling scare in 2008 and 2012 but was ahead in both races for most of the way and won both easily. All had good cause to believe they were solid favorites to win and strategized accordingly.

Harris is different. She leads by just 1.5 points in the RealClearPolitics national average today, and that’s after having arguably the best month of any presidential campaign in modern history. She has yet to debate Trump, yet to do a major interview, and yet to even add a section on policy to her campaign website, all presumably out of fear that her positions will be used against her and cause her numbers to sink.

Harris knows Trump is popular enough to have consistently led Biden in polling for months on end, and of course, she knows that he’s overperformed his polling significantly on Election Day in both of his previous runs for president. She has good cause to fear that if her numbers don’t improve, she’ll fall short in the battleground states she needs.

But so does Trump. Lord knows what sort of delusions are rattling around in that noggin of his, but I’m sure that his top advisers are in touch with some hard realities. He lost the popular vote by significant margins in both 2016 and 2020; he has considerably more baggage after January 6 and his criminal indictments; the center-right “Haley Republicans” who opposed him in this year’s primary are a large and potentially consequential bloc; and the huge turnout among pro-choicers in state abortion referendums has made that issue a major liability for him.

Both campaigns should, and I think do, worry that their respective bases won’t be enough to drag them over the finish line this time. They’ll need to persuade voters in the center to win. So that’s what they’re doing.

Which is also a very weird development in modern political campaigns.

It shouldn’t be. Moving away from one’s base and toward a majority in general elections is what democracy is designed to get candidates to do. But as the parties have become more polarized, the persuadable middle has shrunk; because there are fewer votes to be had there, presidential candidates have focused more on motivating their respective bases to turn out than on flipping centrists. We’ve had “base elections” every four years since 2012, at least.

This year, because neither nominee is a solid favorite, we have an old-fashioned “persuasion election.” That thin band of persuadable voters in the middle will probably prove decisive, so Trump and Harris are competing for them, with the former moving left on abortion and the latter moving right on immigration. In so doing, they’re converging on policy.

And ironically, they’re only able to do so because their respective bases are so polarized.

That’s a familiar story with Trump. After a decade of conditioning the right to treat loyalty to him rather than to conservative principles as the touchstone of Republican politics, he has carte blanche from his base to say whatever he needs to win. Prominent pro-lifers are full of sound and fury about his latest tack toward the left on abortion, but it signifies nothing, as they know where their supporters’ highest political allegiance lies. Trump can go on promising to veto a federal abortion ban with impunity, confident that pro-lifers aren’t going anywhere.

The surprise is that Harris also enjoys a degree of carte blanche from her exuberant base that’s unusual for a Democrat. Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden had to take great pains in 2016 and 2020 not to antagonize the left after fending off challenges from Bernie Sanders, limiting the extent to which they could pivot to the center after the primary, but Harris is under no such constraint. After her party was liberated from a second Biden campaign and she rewarded progressives by choosing Tim Walz to be her running mate over centrist Josh Shapiro, she got an ideological free pass for the general election. And she’s taking full advantage.

There’s a paradox here. Voters and activists in both parties have swallowed so much apocalyptic rhetoric over the past decade about their opponents’ plans to destroy America that they’ve grown more willing to let their own candidates mimic the other party’s plans on key policies. Keeping the bad guys out of power is so important that it’s now all but a patriotic duty to co-opt their strongest issues for the sake of victory.

As one of my editors put it, we’ve ended up with both sides simultaneously insisting somehow that the stakes of this election are incredibly high and that policy doesn’t much matter. Only a hyperpolarized electorate is willing to write its candidates a check as blank as that.

So Trump and Harris each enjoy an opportunity, courtesy of their respective bases, to try to steal the other’s issues. And each has the political means to take advantage of that opportunity, as neither has evinced any deep commitment to ideological principle that would prevent them from pivoting to the center as a matter of intellectual honesty. Harris has gone from a pretend socialist in the 2020 Democratic primary campaign to a pretend moderate now, and Trump has never much cared about policy apart from a few discrete passions like immigration and tariffs.

Each also has a strategic motive to converge on policy, beyond simply pandering to undecided voters by taking the popular position on key issues.

Good vibes and bad.

The fact that the race is so tight has made both candidates more cautious than they might otherwise be.

Trump had nothing to lose with his freewheeling 2016 campaign, when he wasn’t expected to make it out of the primary. Then he ended up in a deep polling hole in the 2020 race, justifying a more aggressive approach in hopes of playing catch-up.

But now he’s effectively tied with Harris. Instead of turning him loose at rallies to tick through the day’s grievances, his aides are begging him to be more disciplined with his message, even sending him to the podium with a binder of talking points to read from.

Harris, meanwhile, is plainly so nervous about her habit of putting her foot in her mouth that she still hasn’t scheduled an interview after promising some time ago to do so before the end of the month. According to Politico, her strategic ambiguity on policy has reached the point that even Tim Walz is being held back from solo interviews because “he might not have a full command of where Harris is on every issue. As someone pointed out to us last night, Harris talks about the ‘opportunity economy,’ but if Walz were asked to define it, would he know how?”

Would she?

To return to the boxing analogy from earlier, both fighters are clinching because they’re afraid of making a mistake that will get them knocked out. Despite the high risk each has of losing, I think both have convinced themselves that they’re ahead on points and more likely to win by decision than by taking a risk that leaves them exposed.

And both have good reason to feel that way. Depending on how you look at it, the “vibes” in this race strongly favor one or the other. So long as they can focus voters on those vibes instead of on policy, they’ll win. The obvious way to do that is to move toward their opponent’s position on major policy liabilities, neutralizing those issues and leaving voters to form their electoral preference on other grounds.

For Trump, the case for a “vibes” campaign is straightforward. Joe Biden is a remarkably unpopular incumbent, and remarkably unpopular incumbents—or their vice presidents—seldom win. The sheer weight of public exasperation with inflation, the border crisis, and the cover-up of Biden’s cognitive decline will ultimately crush Harris, he’s betting, even if he’s too busy hawking digital trading cards to articulate a policy case against her on the stump.

Why on earth would he dig in his heels on banning abortion, alarming gettable voters in the middle, when he can simply hand-wave it away and let anti-Biden “vibes” carry him across the finish line?

Harris also has a seductive “vibes” argument. She’s running against a convicted felon whose last major act as president in his first term was trying to stage a coup. Her “happy happy joy joy” campaign has raised her net favorability from minus-17 points to less than minus-2 in a month. Many voters who couldn’t talk themselves into giving Old Man Biden another four years have come scrambling back to her since she replaced him as the Democratic nominee, erasing a 3-point national lead for Trump and then some.

The fewer contrasts she draws with Trump on policy, the fewer excuses voters have to not let themselves be guided by the antipathy they’ve developed for him over nine very long years. If voters go into the booth letting “vibes” determine their vote, with Harris promising a fresh start for America and Trump promising a new season of the Trump Show, she’s gambling that she wins.

That’s why her campaign reportedly wants the candidates’ microphones to be “hot” throughout their debate next month, of course. During the first debate between Trump and Biden in July, each candidate’s microphone was silenced when the other was speaking, inadvertently helping Trump to seem more self-disciplined than he naturally is. Harris doesn’t want him to be disciplined. She wants the Trump Show, expecting that Americans will vote to cancel it in November if they’re reminded how much they dislike it.

Bottom line: Both candidates have somewhat credible claims of being the “change candidate” in the race, and the change candidate usually prevails on vibes over a disliked incumbent. It’s just that Trump believes the sitting vice president is the de facto disliked incumbent on the ballot this year, while Harris believes the former president she’s running against is.

One of them will be wrong—unless we end up with a 269-269 Electoral College tie, and that certainly won’t happen, right?

Either way, neither has a strong incentive to take bold ideological stands on policy that might upset their “vibes” strategy and obscure their appeal as the change agent in the race. From now until November, we’re more likely to see a bidding war between the candidates over popular welfare-state programs than old-fashioned ideological combat between dramatically different visions of government.

Which I suppose means … nationalism wins in the end? Big spending, law and order, and disinterest in religious priorities like banning abortion and gay marriage are all hallmarks of post-Christian nationalism with which Democrats can find common ground. Harris might have struggled to pull off the sort of harmonic convergence on policy she’s executing with Trump if she were facing a traditionally conservative opponent this year. How fortunate for her that she isn’t.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.