Everyone loves a “Dems in disarray” news cycle, but I find myself enjoying the current one less than usual knowing it was inspired by murder.

Premeditated homicide typically doesn’t warrant sharp disagreement within political parties—and in fairness, congressional Democrats are formally united in their belief that murder is bad, mmmkay. The dispute has to do with whether a certain politically tinged murder is easier to sympathize with than others.

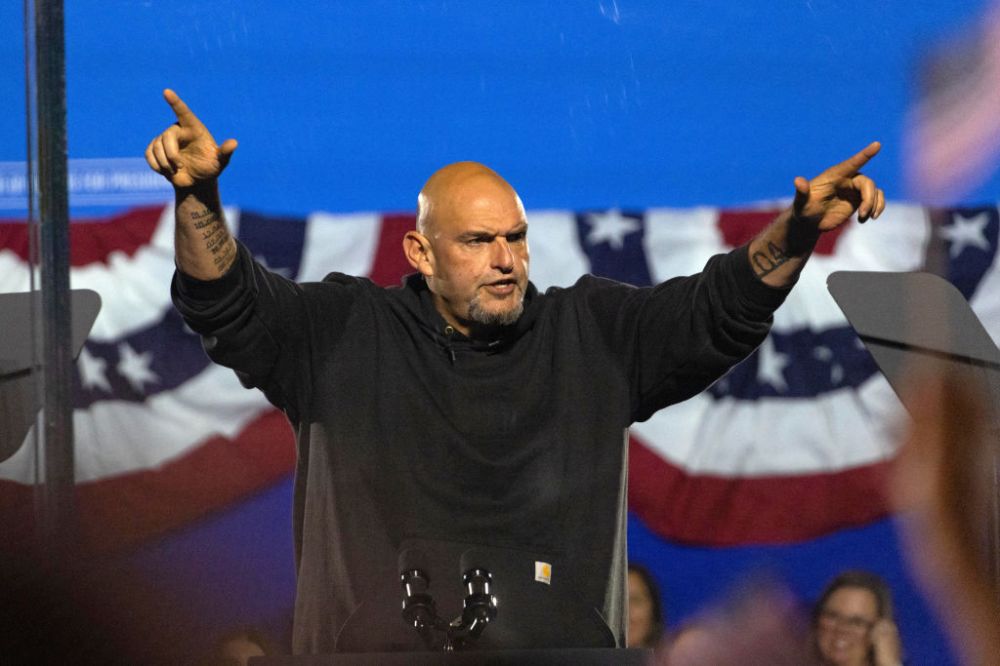

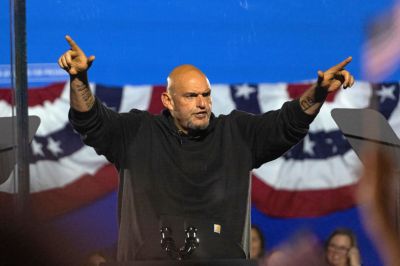

Representing the “no” camp are Pennsylvania’s two highest-ranking Democrats. “He’s the a–hole that’s going to die in prison,” Sen. John Fetterman said recently of accelerationist heartthrob Luigi Mangione, the alleged killer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. “Remember, [Thompson] has two children that are going to grow up without their father. ... It's vile. And if you've gunned someone down that you don't happen to agree with their views or the business that they're in, hey, you know, I'm next, they're next, he's next, she's next.”

Gov. Josh Shapiro was also unequivocal. "In America, we do not kill people in cold blood to resolve policy differences or express a viewpoint,” he said after Mangione’s arrest in Altoona. “In a civil society, we are all less safe when ideologues engage in vigilante justice. In some dark corners, this killer is being hailed as a hero. Hear me on this: He is no hero.”

Shapiro’s and Fetterman’s party just lost Pennsylvania’s presidential race, Senate race, attorney general race, and three most competitive House races to Donald Trump and his populist Republicans. Coincidentally.

Representing the “yes” camp are two of the Democratic Party’s leading progressive lights. “Violence is never the answer, but people can be pushed only so far,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren crowed after Thompson’s death. “This is a warning that if you push people hard enough, they lose faith in the ability of their government to make change, lose faith in the ability of the people who are providing the health care to make change, and start to take matters into their own hands in ways that will ultimately be a threat to everyone.”

Following an outcry, she clarified that she certainly didn’t mean to imply that the killing was morally justified. Murder is bad, mmmkay?

On Thursday Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez also took care to check the “murder is bad” box—before framing Thompson’s murder as a form of self-defense. “This is not to say that an act of violence is justified, but I think for anyone who is confused, or is shocked, or appalled, they need to understand that people interpret, and feel and experience denied claims as an act of violence against them,” she explained. “When we kind of talk about how systems are violent in this country, in this passive way, our privatized healthcare system is like that for a huge amount of Americans.”

It’s unclear what sort of “violence” UnitedHealthcare could have inflicted on Mangione given that he’s never been enrolled with the company, but no matter. Like Warren, Ocasio-Cortez hails from one of the bluest jurisdictions in the country, where the only worry a Democratic incumbent has is being outflanked on her left in a primary. Coincidentally.

Dems are in disarray over Luigi Mangione. It seems to me that the nature of that disarray is two different forms of populism in conflict.

The secret sauce.

The shining lesson of last month’s election, universally agreed upon by Democrats, is that the party has lost touch with the working class and urgently needs a way to woo back downscale voters who are moving right.

You can’t win national races in America by piling up ever bigger margins with college graduates. There simply aren’t enough of them. Either the left will become more populist by 2028, or it’ll lose again.

But which flavor of populism, cultural or economic, should it emphasize?

Donald Trump’s secret sauce on November 5 was that his political recipe contained both flavors. It’s bizarre to think of him as an economic populist when his top fiscal priority is extending top-heavy tax cuts and his inner circle is overflowing with billionaires, including the richest person in human history, but the salience of inflation provided steady wind in his sails. When he was asked last weekend why he won, he astutely replied, “Very simple word: groceries.”

It’s a little more complicated than that, as he wasn’t above chumming the electoral waters with fiscally unsound populist panders to blue-collar voters. Just yesterday he announced his opposition to automating U.S. ports, an atrociously inefficient economic policy but one that has the political virtue of endearing him to union members by preserving unnecessary jobs.

Trump was basically right, though. “Groceries”—specifically, what they used to cost during his first term as president—turned him into the economic populist on the ballot this year. Although maybe not for much longer.

He would have been the cultural populist on the ballot as well even if we hadn’t had a years-long border disaster to focus voters’ attention on immigration. A progressive lawyer from San Francisco like Kamala Harris would have had trouble seeming salt-of-the-earth relative to the King of England; pitted against an anti-woke blowhard like Trump, she was sure to bleed lunchpail votes. But the border crisis—the most severe in American history, it turns out—was the icing on the cake, chronically reminding voters of the elite left’s ambivalence toward basic law enforcement.

Combine that with public angst about crime in major cities and the gap in cultural populism between the two candidates this time was arguably greater than it was in 2016. A law-and-order immigration restrictionist was tailor-made for this political moment.

Which prong of Trump’s appeal, the economic side or the cultural side, should Democrats prioritize in reintroducing themselves to the working class?

“Both!” you might say, reasonably enough. If that was the secret sauce for Republicans this cycle, naturally the other party should try to re-create it.

But that’s easier said than done.

Cultural or economic?

It is very hard to imagine a politician like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez remaking herself as a border-enforcing crime fighter to complement her economic populism.

It wouldn’t have been so hard a generation or two ago, when many leftists still regarded illegal immigration skeptically because of the downward pressure it applied to Americans’ wages. But modern leftism is consumed with erasing “privilege” of all sorts—by race, by sex, by national origin, by religion, not just by class. AOC isn’t going to take sides with the “privileged” majority against the underprivileged at home and abroad by being a hard-ass when the latter breaks the law.

That’s because left-wing economic populism is revolutionary in spirit. It doesn’t want to “reform” private health insurance; it wants to abolish it. It yearns to wage political war on capitalism’s most predatory elements. It’s Jacobin at heart, which is why it was so quick to elevate Luigi Mangione to icon status. Tearing down “the system,” not running interference for a social order dictated by the ruling class, is its highest ambition. It craves jailbreaks.

That makes it an awkward fit for a centrist normie like Josh Shapiro, whose entire political “brand” is maintaining order amid disruption. His splashiest success as governor was repairing Interstate 95 in two weeks after an overpass collapsed, beating the estimated timetable by months and averting endless traffic snarls for Pennsylvanians. That might seem trivial but government responding effectively to a quality-of-life crisis—especially when that government is run by a Democrat—is uncommon in modern America.

Shapiro has been keen to make an enemy of the left’s Jacobins too. He was quick to take credit after the National Park Service abandoned its plan to tear down a statue of William Penn in Philadelphia. And he loudly condemned the bigotry of pro-Palestinian protesters on campus this past spring, complaining that “if you had a group of white supremacists camped out and yelling racial slurs every day, that would be met with a different response than antisemites camped out, yelling antisemitic tropes.”

No doubt he’ll support some form of health care reform when he runs for president in 2028, but he can lean only so far into left-wing economic populism before his law-and-order appeal begins to erode. His cultural populism is counterrevolutionary in spirit, after all; he’s the Democrat you turn to when the left’s impulse toward disorder, economic or otherwise, has you spooked. He can’t protect you from the guillotine if he’s helping to drop the blade.

Greater disruption or greater stability: The left’s economic populists and its cultural populists have different ideas about how best to serve the working joe. Go figure that Shapiro and Fetterman would find themselves on the other side of l’affaire Mangione from Ocasio-Cortez and Elizabeth Warren.

For the latter two, a health insurance fat cat getting what’s supposedly coming to him is an unfortunate but arguably necessary jolt to the economic order. The disruption caused by Brian Thompson’s murder may be shocking but there are always shocking moments in a revolution when the oppressed begin to assert themselves against their oppressors. No rotten system was ever deposed without blood being spilled.

For the former, while it may seem strange to treat a rudimentary moral principle like “murder is bad” as a bold gesture of social stability, it is pretty bold in the context of recent Democratic politics. Shapiro and Fetterman belong to a party whose overeducated activist class has championed defunding the police and abolishing prisons, treated border enforcement as a form of racism, challenged the idea that gender is derived from biology, and celebrated Hamas as a vanguard of progressivism. For a Democratic politician to side with the average joe by insisting that the sky is blue and murder is wrong, knowing from experience that his Jacobin base will angrily contrive a reason to say otherwise, is no small thing.

One of my editors asked me this morning how I thought Kamala Harris would have reacted to Brian Thompson’s murder if it had happened during the campaign. “During the campaign she would have sounded like Shapiro and Fetterman,” I thought, knowing how eager she was to impress undecided centrist voters with her law-and-order cred. “But the 2019 version of Kamala Harris who bent over backward in that year’s Democratic primary to pander to progressives? She would have sounded like Warren and AOC.”

That’s the party’s dilemma in a nutshell. Can any leftist successfully blend the two populisms, as Trump has? How do you advance a working-class economic agenda without leaving the center suspicious that you’re a burn-it-all-down radical? How do you advance a working-class cultural agenda without leaving the left suspicious that you’re a status-quo simp at heart?

Fettermania?

Maybe Fetterman can do it.

Democrats as a bunch certainly can outcompete Republicans on economic populism if they make the effort. They’re traditionally the party of labor and social welfare programs, and they’ve proved far more serious about reforming health care over the past 15 years than an opposition that’s perennially stuck in the “concept of a plan” phase has. Joe Rogan may be a red-pilled MAGA guy now but the occasion of Thompson’s murder left him briefly sounding like the Ocasio-Cortez progressive he used to be. Democrats lost him; maybe they can win him, or people like him, back.

Trump’s second term will probably help them along. Tax cuts that mostly benefit the rich, rent-seeking oligarchs feeding from the public trough, blatant self-dealing in the Oval Office, and all of it possibly happening as “groceries” begin to get more expensive again: That would hand liberals an easy opportunity to reposition themselves as allies of the average joe in a new Gilded Age.

The tricky part for the left is the cultural part. To neutralize the right’s advantage on law-and-order populism, a Democrat would need to spend an unlikely amount of political capital establishing himself as a “different kind of liberal” culturally.

Fetterman has done it. Over the past year he’s distinguished himself by supporting Israel unwaveringly against jihadist barbarians, by defending immigration enforcement as a legitimate priority, and lately by treating Mangione’s apologists with the contempt they deserve. Last month he scolded the media for sneering at Rogan and his “bro” fans. “I love people that are absolutely going to vote for Trump,” he said of them. “They’re not fascists. They’re not those things.”

He’s so eager to be a different kind of liberal that he set up an account on Trump’s Truth Social platform this week and used his first post there to call on New York’s governor to pardon Trump for the hush-money offenses of which he was convicted. On Wednesday he sounded like a Republican in loudly affirming his support for Elise Stefanik as Trump’s ambassador to the United Nations.

Maybe this is nothing more or less than a guy worried that his state is turning into Ohio politically and getting ahead of the curve in positioning himself as a red-state Democrat ahead of reelection in 2028. But I think it makes him potentially the most interesting liberal in Congress during Trump’s second term.

The smart play for Fetterman is to side with Trump wherever possible on cultural matters and to outpopulist him wherever possible on economic matters. The words “wherever possible” carry a lot of weight here: As much as Fetterman might see value in defending mass deportation, the process might plausibly turn so ugly that it’ll become impossible politically for a Democrat to carry water for it. For a liberal, “law and order” has its limits.

But economic sore spots like tax cuts, health care, and plutocracy writ large are perfect opportunities for Fetterman to rebuild some goodwill with progressives and position himself as a left-populist scourge of Trumpism by criticizing the White House harshly. If he’s skillful about it, his economic views could be a gateway for Democratic voters to move toward him on cultural matters pertaining to public order while his cultural views could be a gateway for Republican voters to move toward him on economic policy.

He might have the recipe for the secret sauce. If not him, who?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.