Hey,

Yesterday, I recorded a long episode of The Remnant on political philosopher Leo Strauss. Yale political philosopher Steven Smith served as my tour guide. I bring that up for a few reasons. First, because the suits want me to promote our excellent array of podcasts more. Second, to illustrate that for all my talk about the perils of audience capture and pandering to the needs of the marketplace, I am not immune to such seductions. Last, to establish that I was on a bit of a Leo Strauss kick before our friends at Persuasion posted an excerpt from a Strauss lecture titled “German Nihilism.” And now having read it, that’s what I want to talk about.

This is not exactly what might be called a “best practice” for pundits. No one says, “I’ve got a couple hours before I have to go to CNN, so let me write about observations from one of the 20th century’s most important, complex, and careful philosophers about nihilism!” Well, almost no one.

As everyone who saw The Big Lebowski knows, or at least believes, nihilism is not an ethos. And strictly speaking, nihilism, or at least what is frequently called existential nihilism, is the opposite of an ethos.

An ethos is a body or system of beliefs, norms, and ideals that define a person, institution, or society. Nihilism, meanwhile, is the philosophical school that says “lol, nothing matters” (though the “lol” is optional). According to German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, nihilism is “the radical repudiation of value, meaning, and desirability.”

At first I thought that Nietzsche’s use of “desirability” was weird. I mean, does nihilism mean we can’t desire milkshakes or foot massages? Apparently, Nietzsche was using the word Wünschbarkeit, and in context, Nietzsche meant that nihilism refutes the idea that we should yearn for some higher purpose, some great cause. It’s the idea that it is futile to try to answer the question of why we exist. There is no ultimate justification for your strivings for meaning. As it says above the entry to the Newark airport, “Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here.” Or something like that.

The thing that really intrigued me in Strauss’ lecture is his description of how the opponents of nihilism in prewar Germany lost the argument against it.

But I think I need to provide just a bit of context.

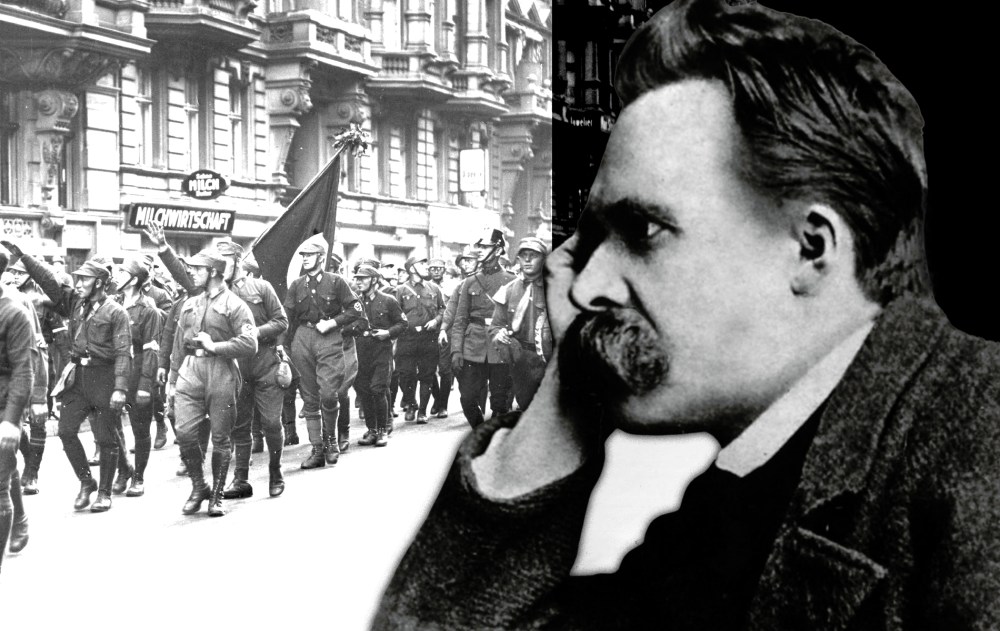

First, the thing you need to know about Strauss’ lecture—which I really do recommend reading—is that Strauss believed that the intellectual project begun by Nietzsche and carried on by Martin Heidegger and that whole crowd of German existentialists and shmucks laid the intellectual groundwork for the rise of Nazism (Strauss, a German Jew, was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust). This is a pretty familiar argument, and a defensible one, even if I think there are important caveats one could make. But I’m not going down that rabbit hole.

Second, as I discussed with Steven Smith, Strauss was a hugely influential critic of modernity, but he was not a “postliberal.” He did not consider himself an enemy of liberal democracy. He just thought—I think—that liberal democracy alone isn’t enough of an ethos to rest society on.

Third, Nazism was only one form of German nihilism. In Strauss’ words, National Socialism was “only the most famous form of German nihilism—its lowest, most provincial, most unenlightened and most dishonourable form. It is probable that its very vulgarity accounts for its great, if appalling, successes.”

There’s lots to think about in that last claim about how vulgarity was the key to its success.

Fourth, the German nihilists weren’t really full-blown nihilists. “The fact of the matter is that German nihilism is not absolute nihilism, desire for the destruction of everything including oneself, but a desire for the destruction of something specific: of modern civilization.”

Last, the thing the German nihilists were rebelling against was not only the louche and decadent liberalism of Weimar Germany, but also the world Marxists were promising just around the corner. During the First World War and postwar period, lots of people were sure that a revolution was coming that would, in Strauss’ words, be defined by “a rising of the proletariat and of the proletarianized strata of society which would usher in the withering away of the State, the classless society, the abolition of all exploitation and injustice, the era of final peace. It was this prospect, at least as much as the desperate present, which led to nihilism.” The nihilists dreaded the “end of history,” fearing it would be boring. And, remember, boredom kills.

In other words, the German nihilists were, more properly speaking, radicals. They wanted to tear down what existed, but they didn’t necessarily want a big nihilist nothing to replace the status quo. They liked the language of nihilism because it was a useful hammer for destroying existing idols, but they wanted to erect new, manly idols in their place. Many of the young nihilists had plenty of that Wünschbarkeit—a yearning for meaning. After all, that was ultimately the appeal of Nazism: Teutonic heroism, a 1,000-year Reich, global conquest, etc. Again, “say what you want about the tenets of National Socialism, dude, at least it’s an ethos.”

According to Strauss, what the young German nihilists “hated was the very prospect of a world in which everyone would be happy and satisfied, in which everyone would have his little pleasure by day and his little pleasure by night, a world in which no great heart could beat and no great soul could breathe, a world without real, unmetaphoric, sacrifice, i.e. a world without blood, sweat, and tears.”

Strauss doesn’t really lay out everyone he has in mind when he talks about the opponents of these nihilists. I am assuming he means Weimar liberals and Christian socialists. But he might also include monarchists, various theologians, traditionalists, conservatives, et al. I don’t want to get too distracted, but the story that only the left detested Hitlerism is exaggerated for all of the obvious reasons.

Regardless, Strauss says (emphasis mine):

[The nihilists] did not really know, and thus they were unable to express in a tolerably clear language, what they desired to put in the place of the present world and its allegedly necessary future or sequel: the only thing of which they were absolutely certain was that the present world, and all the potentialities of the present world as such, must be destroyed in order to prevent the otherwise necessary coming of the communist final order: literally anything, the nothing, the chaos, the jungle, the Wild West, the Hobbesian state of nature, seemed to them infinitely better than the communist anarchist-pacifist future. Their Yes was inarticulate—they were unable to say more than: No! This No proved however sufficient as the preface to action, to the action of destruction.

The new nihilism.

I think this has real relevance for the present moment (and so does Francis Fukuyama, which is why he posted the lecture). The celebratory vulgarity of so many on the MAGA right is a key to their success. When I listen to all of the various postliberals, nationalists, and “do you know what time it is?” types, I hear echoes of the same idea. All of the Flight 93 and “end of America” crap of the last decade feels very similar to the inarticulate rage the nihilists had at the prospect of communism’s looming victory. The fear of “woke communism” taking over everything became a rationalization for doing whatever was necessary to save America, because obviously the current system was inadequate to the task.

In Dawn’s Early Light, Kevin Roberts, the president of the Heritage Foundation, writes:

There’s a scene in the Cormac McCarthy novel No Country for Old Men in which hit man Anton Chigurh has taken a fellow hired gun captive. Holding him at gunpoint and asking about his life’s philosophy, Chigurh asks him, “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” It is a question we must ask ourselves. After all, if what the old conservative coalition understood to be its foundational principles led us to this—the total domination of the Uniparty, the demise of the American working class, and the erosion of the institutions that defined American life —of what use are those principles?

I find this darkly hilarious. For starters, several years ago psychiatrists studied some 400 movies and concluded that the single most fully realized psychopath in cinema was Anton Chigurh. And here the president of the Heritage Foundation is citing him—a fictional character, mind you—as the authority to illustrate why we should no longer follow the “rules”: because they led us to the state of America in 2024.

America had problems in 2024, but that’s deranged.

Note, he is not saying we failed to live up to those rules—a fair claim, especially for a (formerly) conservative think tank called the Heritage Foundation. He’s saying, the rules themselves need to be ditched: Don’t bother quoting the Federalist Papers at me, you beta male cucks and soy boys. James Madison and Alexander Hamilton are no match for the wisdom of a made-up character who assassinates people with a compressed air cattle gun!

The foreword is written by J.D. Vance (because of course). The current vice president —who said last night that pointing out he once wrote for National Review is an insult —writes that “Never before has a figure with Roberts’s depth and stature within the American Right tried to articulate a genuinely new future for conservatism.” Read with Straussian exactitude, that’s sort of true.

Beyond yes and no.

Anyway, back to Strauss. His critique of the opponents of nihilism strikes a cautionary chord with me. “Those opponents committed frequently a grave mistake,” he explains. “They believed they had refuted the No by refuting the Yes, i.e. the inconsistent, if not silly, positive assertions of the young men. But one cannot refute what one has not thoroughly understood. And many opponents did not even try to understand the ardent passion underlying the negation of the present world and its potentialities.”

I’ve spent a lot of time and energy trying to point out that, say, Curtis Yarvin’s “neo-monarchical” program is ridiculous garbage. But that might just be a waste of time in the Straussian analysis, because nihilists really don’t care about the Yes stuff—the stuff that comes after we tear everything down—nearly as much as they care about screaming No. And unless you can rebut the No, the problem will endure.

I think the No stuff is wrong, too. And in my defense, I wrote a whole book about how the No people are wrong. Liberal democratic capitalism is the greatest system of human organization ever realized. Is it flawed? Of course. Does it require upkeep? Abso-frick’n-lutely. But the answer to our problems isn’t to set fire to what is, in favor of a dog’s breakfast of potted ideas of what might be. It’s to teach people why they should be grateful for what we have and how to reapply the principles—the rules—that pulled us out of the muck in the first place.

Now, the good news, for me at least (though maybe not for my editors or readers), is that my CNN hit got canceled so I have a little more time to expand on this point by leaving Strauss for a moment.

Yes and No Marxism.

Back in 2018, I wrote an essay for Commentary titled “Socialism Is So Hot Right Now.” One of the points I made was that whenever people are pissed off about the state of the economy, the culture, or their place in either, socialism gets popular. It’s not because young people, frustrated by high rent or unemployment, start reading Karl Marx or Sidney Webb. They look at the society and say, in effect, “If this is capitalism, then I’m for socialism,” because socialism in the popular mind is basically the antonym for capitalism.

For most of my life and indeed for most of the last 150 years, that’s been the basic rule. What’s changed in the last decade is that the right now plays this game, too. “If this is where the rule brought us, then I’m for the opposite of this rule.” One of the difficulties is that we don’t have a great vocabulary or body of arguments for what to call the opposite thing. We can’t call it socialism or Marxism. So ideological entrepreneurs have busied themselves trying out nationalism, or monarchism, or MAGA. Others, probably wisely, think they should keep the term conservatism, but like Kevin Roberts & Co. they first have to kill it, scoop out its innards, and then wear its skin like a mask. This new “ism” looks a lot like what the lefty kids once meant by socialism, because all alternatives to liberal democratic capitalism are more similar than different. We don’t need another round of horseshoe theorizing, but once more with feeling: Nationalist societies tend to be socialist and socialist countries tend to be nationalist. Once you decide that the “experts” should run the show, the argument becomes largely a stylistic one about which tribe of illiberals you think should be in charge, and which autocrat should lead them.

Strauss’s point about Yes and No is crucial here. The thing that initially drove the nihilists wasn’t the Yes—the system that would replace the Weimar Republic or Western liberal democratic capitalism generally. It was the passion of their No. The What Comes Next thing was important, but secondary.

What I find fascinating is that what was true about intellectual passions that led to the rise of Nazism were also true of communism. Let’s never forget that Marx, too, was a post-liberal.

The Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe is an effort to print every single thing that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote. So far, it’s up to 65 volumes. The plan is to finish the project at 114 volumes. Estimates for the total number of pages Marx wrote are around 25,000 to 30,000. We all know from college term papers that you can really stretch things out by playing with the margins and fonts—my go-to font back in the day was Courier because the characters look small, but the kerning (space between letters) was generous. But if we assume the standard 500 words per single-spaced page, that means Marx wrote between 12 million and 15 million words.

And yet, the total number of words Marx dedicated to describing how communism would actually, you know, work, depending how you count, is probably a few pages. Maybe a dozen. Longer than a tweet thread but shorter than a meaty magazine article. The rest of it is vibes, gripes, and conspiracy theories about capitalism—most of which are wildly wrong or at least one-sided.

What little Marx does offer about things will work is pretty vague and aphoristic. For instance, in The German Ideology, he describes how awesome communism would be in this famous passage:

... in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic. This fixation of social activity, this consolidation of what we ourselves produce into an objective power above us, growing out of our control, thwarting our expectations, bringing to naught our calculations, is one of the chief factors in historical development up till now.

Imagine you’re a government official in a freshly hatched Marxist regime. I challenge you to explain how this will help you govern. Like how will this, you know, work? How does the state generate revenue to pick up the garbage or build a sewer? Who tells the food inspectors they can’t go fishing yet? Who will make sure the rapists and murderers are caught and punished? How, again, will that work? Marx has no clue and doesn’t offer any.

Sure, doctrinaire Marxists will say I’m missing the point because under Fully Realized Super Terrific Communism, the state will “whither away.” But my response to that is: That’s really, really stupid. I don’t mean that in a juvenile way. I mean it’s literally stupid according to everything we know about history, anthropology, sociology, psychology, and economics. It’s a pie-in-the-sky fantasy on a world-historic scale.

But Marxism has endured to the extent that it has precisely because it’s a fantasy. It’s the ancient promise of a Kingdom of Heaven on Earth, gussied up with scientific blather and cotton trade statistics. In its various forms and iterations, it remains the left’s response to what is. And, as Strauss suggests with the nihilists, pointing out that it’s wrong is insufficient because such refutations can’t touch the burning desire for it to be right.

The conservative response to Marxism was always to lean into the superiority of liberal democratic capitalism, the constitutional order, and traditional notions of morality, patriotism, and religion. Sometimes to excess, to be sure. But that was conservative reflex. I don’t see why that should be any different in response to those on the right who offer their own pie-in-the-sky fantasies, even if that risks raising the ire of Anton Chigurh and his disciples.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.