Editors’ note: We hope you enjoy this edition of Techne, a new newsletter by Will Rinehart dedicated to unraveling the complex forces shaping tech policy and innovation. To learn more, check out the introduction Will wrote last week, and be sure to sign up here to receive future editions in your inbox.

Welcome to the inaugural issue of Techne! A couple of lines from the poet C.P. Cavafy stuck with me as I was writing this first newsletter. It’s from the poem Ithaka, about the start of a journey: “As you set out for Ithaka / hope your road is a long one.” So whatever you’re tackling this week, “don’t hurry the journey at all / Better if it lasts for years.”

Notes and Quotes

- Ian Brooke just announced the invention of a brand new jet engine that uses electric motors to drive a compressor. This new Adaptive Cycle Jet Engine enables efficiency at every speed, making launches into space way cheaper. As Andrew Côté bluntly explains, the new device makes it so pilots can “skip using rockets when they suck.”

- The European Commission slapped Apple with a $2 billion fine this month, claiming the company set unfair rules for music streaming apps. The move is part of a larger compliance effort by the commission’s Digital Services Act package, which aims “to create a safer digital space where the fundamental rights of users are protected and to establish a level playing field for businesses.” The six gatekeepers singled out by the commission are largely the companies you’d expect: Alphabet/Google, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta/Facebook, and Microsoft. Megan Kirkwood has a good rundown of some of the new requirements.

- A bill to divest TikTok quickly sailed through the House of Representatives, and President Joe Biden has said he will sign it if it gets through Congress.

- Anthropic, one of the big players in the AI world, launched its Claude 3.0 model. According to its tests, this new version of Claude bests OpenAI’s GPT-4 in undergraduate-level knowledge, math problem-solving, and more.

- Did White House and executive agency officials violate the First Amendment by encouraging companies like Facebook and Twitter to censor posts about the COVID-19 pandemic, election fraud, and Hunter Biden’s laptop? The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments about this question next Monday for the case Murthy v. Missouri. Here’s the SCOTUSblog entry, as well as a House subcommittee report on how the process worked. Often, federal agencies would send information to universities which then pressured social media companies to take the content down. In some cases, the government used self-deleting message apps, so who knows what they were asking.

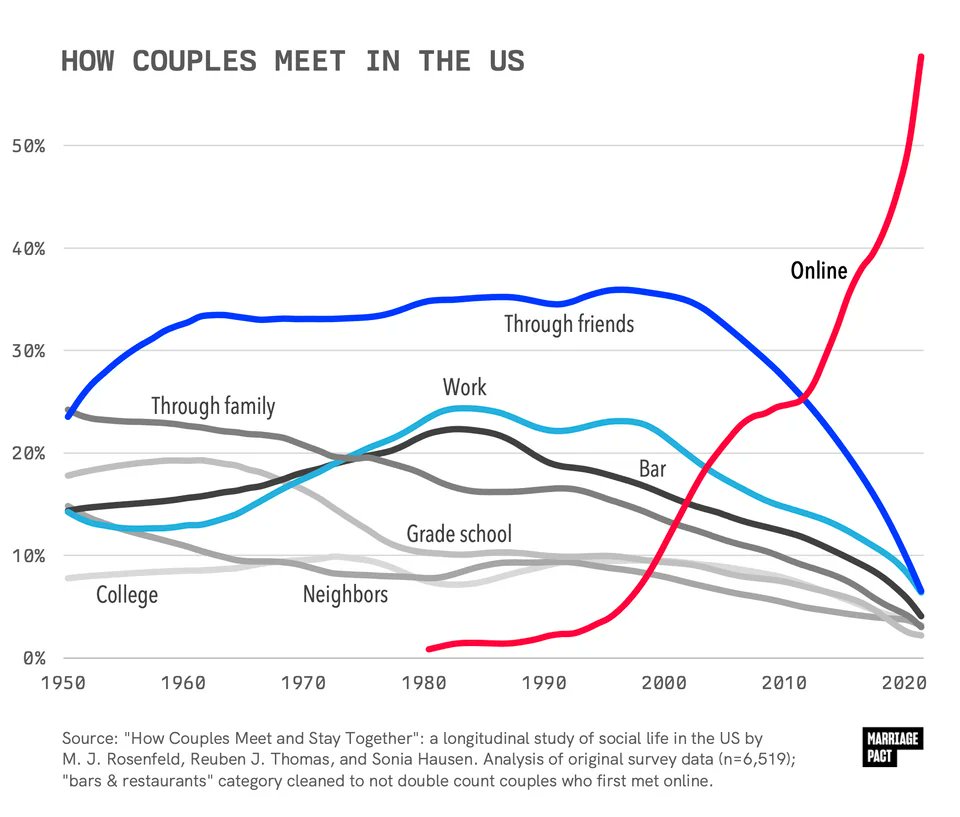

- From Nick Kapur: “Basically every category of meeting one’s romantic partner is diving toward zero and getting eaten by online.”

- Eric Fruits at Truth on the Market spells out the court challenges to the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) order on digital discrimination. The order includes pricing regulation, although the law explicitly forbade it.

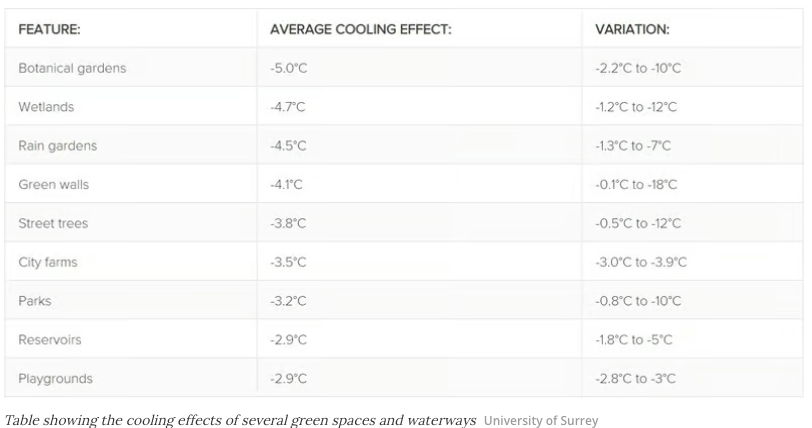

- An article in New Atlas includes estimates of the effects of various city hardscapes—wetlands, rain gardens, and street trees—on local city temperatures. Botanical gardens can cool city air by an average of 5 degrees Celsius, for instance.

- A large helium deposit was discovered in Minnesota’s Iron Range last month. Helium is used for resonance imaging, laboratory applications, electronics and semiconductor manufacturing, and a range of other engineering and scientific applications. But its supply is limited. This announcement, however, follows the recent discovery of 2.34 billion metric tons of rare-earth elements in Wyoming. “If wisely exploited, this find—estimated to be the richest in the world—will give the U.S. an unparalleled economic and geopolitical edge against China and Russia for the foreseeable future,” writes Michael Auslin.

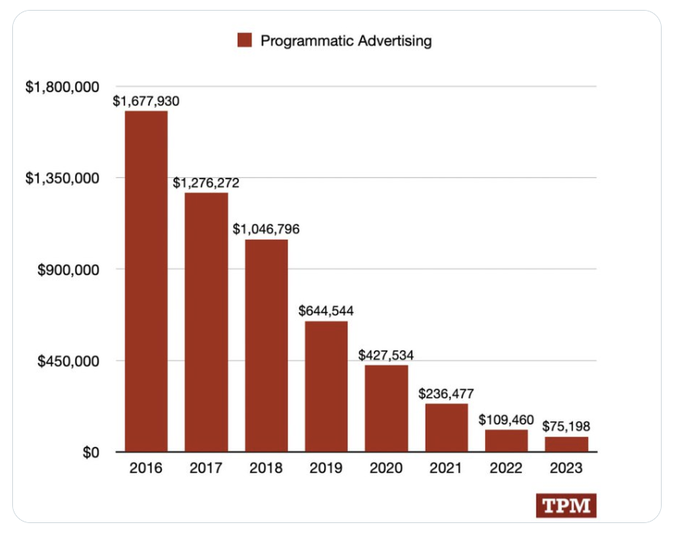

- Derek Thompson shared the following graphic from Josh Marshall, founder of Talking Points Memo, about online ad revenue. Why the dramatic drop? As Marshall tells it, Meta and Google ate the field, just as firms decided it was more cost-effective and brand-safe to send their ads away from news sites. Marshall’s thread adds more context.

Why I’m Out of Step with My Generation

Among my millennial friends, and even more so for Gen Z, it’s common to believe that the United States is in terminal decline. But I remain an outlier because I think the United States’ best days could still be ahead. The country faces challenges, to be sure, but we have an abundance of resources and minds to meet those challenges. In this inaugural issue of Techne, I want to explain why I’m optimistic.

The stubbornness of American abundance.

We have so much in the United States.

Depending on how you count it, the United States is either No.1 or No. 2 in total arable land. We are a top cereal and a top agricultural exporter. And the United States contains most of North America’s chernozem belt, a region of intensely productive soil.

The United States has the second largest mineral wealth in the world, estimated at $45 trillion. While most of that wealth is in coal and timber, we have substantial deposits of copper, lead, molybdenum, phosphates, rare earth elements, uranium, bauxite, iron, nickel, potash, and many other minerals that make the modern world.

We are a large, wealthy country close to the equator. I think most are surprised to learn that Kansas City has more sun hours in a year (2,814) than Rome (2,470). All of that sun means solar power, which has been a boon for the renewable power source in places like Texas.

The United States is also energy independent for the first time since the early 1950s. Investments have led to a boom in crude oil and natural gas production. Since 2019, exports have been higher than imports, and in 2023 the United States was the largest oil producer in history.

The United States also has massive reserves of freshwater: the Mississippi River System, the Inland Waterway, and some 95,471 miles of shoreline. We have a large landmass, aren’t in open conflict with our neighbors, and we have oceans to our east and our west.

But more important than these natural resources, the United States is abundant in the ultimate resource: people.

Compared to other rich, industrialized nations, the United States has a big, young, educated population. Millennials number 72.1 million in the United States, and they are being followed by Gen Z, which numbers 69.6 million. These two large cohorts have kept our median age below the averages of our peers, creating a population pyramid that is far less top-heavy. Sure, our falling birthrate poses challenges, but we won’t be facing the immediate problems gripping countries like Germany, Italy, Japan, and South Korea. They are all aging rapidly and have top-heavy population pyramids, which means social safety nets will have lots of older people and fewer young workers to pay for them. In Japan, just 758,631 babies were born in 2023, both a 5.1 percent decline from the previous year and the lowest number of births since Japan started compiling the statistics in 1899.

Instead, the U.S. will be among a rarified few countries that are developed and will continue to grow into the near future. As I’ve written before, “That cohort is small though, and only includes Canada, Australia, Sweden, New Zealand, Norway, and maybe the United Kingdom. But that’s about it. Every developed country in the world will lose significant populations in the coming decades.” As millennials and Gen Zers age into middle adulthood, the demographic structure of the United States will offer a distinct advantage, maintaining a large base of consumers, investors, and taxpayers that will continue to propel growth.

Despite recent missteps at some high-profile universities, our education system still ranks at the top in the world. Eight of the 10 best schools globally are located in the U.S. Education, along with opportunity, make this country coveted among immigrants.

The United States is also home to Silicon Valley, a region still dominant in tech and entrepreneurialism. Despite its flaws, the region is still a place where, as one commenter explained, we have “no nostalgia for the old days, because we are always looking to rip the old stuff up and throw it away for something better.”

That constant demand to do better has bred success. Eight of the world’s 10 largest companies by market capitalization are based in the U.S.

We have abundance. It is a stubborn fact.

The U.S. is exceptional.

I'm also increasingly out of step with my generation because I see 1789 as the founding year of this country.

I’m not here to praise the Founders—they were at best wise barbarians. Instead, I want to recognize the pragmatic brilliance of the Constitution and the culture it created. Ours remains the longest lasting written constitution for a good reason. It is an aspirational document that came from the crucible of argument between federalists and antifederalists.

The preamble lays out the challenge: to be better than before, to strive to uphold justice, to maintain internal peace, to provide for national defense, to promote the general welfare, and to secure the freedoms for ourselves and for future generations.

It is from that rootstock that our exceptionalism grew—and yes, I do think the United States is an exceptional country. It’s exceptional because it’s a country built on a set of ideological commitments, which are constantly being fought over in public. Unlike some who see this country as a “unique source of incompetence and malevolence,” I still fundamentally believe in the American Experiment. We air our dirty laundry for everyone to see.

No, we haven’t always upheld freedom, liberty, and justice. But each generation’s political leaders are still fighting over these ideologies. This constant contestation of freedom, in the words of the historian Eric Foner, remains “America’s strongest cultural bond and its most perilous fault line.”

No country is without its faults, but the United States still embodies those ideals that were set down so many years ago. Liberty and the equality of the individual matter. And more importantly, this is a country where excellence is celebrated.

A better tech-optimism.

None of this is meant to convince you that “actually things are good!” Rather, this is a way to make a simple point: I’m fundamentally optimistic about the next 50 years for this country and Techne will reflect that optimism.

Tech-optimism has gotten a bad rap—and for good reason. Especially in Silicon Valley, the mindset has come to express a “blind faith in the power of technology to cure all ills, and particularly, to create economic growth.” But Techne won’t be advancing unbridled, unconstrained optimism. I’m shooting for something more practical and useful.

Psychologists know people love to read negative articles. Our brains are wired for pessimism. Not surprisingly, news articles have gotten more negative over time. There is something deep within us all that demands doomerism.

But if you want to get something done, optimism is more productive. This is one place where researchers agree: “Optimists are not simply being Pollyannas; they’re problem solvers who try to improve the situation.”

So what can be done to improve our situation? My former colleague Eli Dourado has laid out some of the action items:

If we wanted to raise American productivity, for example, we could simplify geothermal permitting, deregulate advanced meltdown-proof nuclear reactors, make it easier to build transmission lines, figure out why high-speed rail is so expensive, fix permitting generally, abolish the Jones Act, automate our ports, allow drones to operate autonomously, legalize supersonic flight over land, reduce occupational-licensing requirements, train more medical workers, build more hospitals, revamp our pandemic-response institutions, simplify drug approvals, deregulate land use to allow denser housing and mixed-use neighborhoods, allow more immigration, cancel inefficient programs, restrict cost-plus procurement contracts in favor of more effective methods, end appropriations based on job creation, avoid political direction of scientific research, and instill urgency in grantmaking.

But there’s more we can do, especially in areas that don’t normally fall into traditional tech policy.

We also need to create opportunities for anti-aging research, enhance ecosystems through wildlife corridors, replant seagrass and oyster beds, channel research dollars to atomically precise manufacturing, develop commercialism in space, simplify regulatory regimes, better understand how aerosols interact with the climate, bring back the American chestnut, work toward budget-friendly ultraviolet lights to kill viruses, set up moonshots for carbon sequestration and for sea oxygenation, eradicate disease-bearing mosquitoes, eliminate rabies, allow for easy access to prescription glasses online and access telehealth services, plant trees in targeted areas, develop cheap metagenomic scanning, and build desalination plants, just to name a few.

Contemporary tech criticism displays a kind of anti-nostalgia. Instead of being reverent for the past, anxiety for the future abounds. In these visions, the future is imagined as a strange, foreign land, beset with problems.

Techne won’t be that.

Instead, it will attempt to understand and record the better future that is being built.

Next week, I’m going to dive into what’s happening with TikTok, which is sure to make me lots of friends …

Until then,

🚀 Will

Research and Reports

On March 6, the Federal Trade Commission hosted its eighth annual PrivacyCon, bringing together researchers and regulators to discuss consumer privacy and data security. There are usually some interesting papers presented at the event, and here are a couple I’ve got lined up to read:

- Kraft, Skiera, and Koschella (2023): “This article examines one of the world’s largest privacy initiatives, Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT), introduced with iOS 14.5 in April 2021, to understand the differences in tracking and economic outcomes between both approaches. ATT requires each app to obtain explicit consent to track users across other publishers’ apps (tracking if users opted in); before ATT, Apple permitted tracking under implicit consent (tracking unless users opted out) … ATT reduced the share of trackable (versus untrackable) Apple traffic in the United States by 55 percentage points, from 73% to 18%. Given the observed 51% higher prices for trackable (versus untrackable) ad impressions, this decline translates to a 21% fall in ad revenue from Apple users for publishers. In other countries, the decline in tracking rates ranged from 24% to 59%. Cultural differences account for differences in the tracking rates across countries.”

- Müller-Tribbensee, Miller, and Skiera (2024): “Prestigious news publishers, and more recently, Meta, have begun to request that users pay for privacy. Specifically, users receive a notification banner, referred to as a pay-or-tracking wall, that requires them to (i) pay money to avoid being tracked or (ii) consent to being tracked … The price for not being tracked exceeds the advertising revenue that publishers generate from a user who consents to being tracked. Notably, publishers’ traffic does not decline when implementing a pay-or-tracking wall and most users consent to being tracked; only a few users pay. In short, pay-or-tracking walls seem to provide the means for expanding the practice of tracking. Publishers profit from pay-or-tracking walls and may observe a revenue increase of 16.4% due to tracking more users than under a cookie consent banner.”

- Mayer, Zou, Lowens, et. al. (2023): Data breaches are prevalent. We provide novel insights into individuals’ awareness, perception, and responses to breaches that affect them through two online surveys … Overall, 73% of participants were affected by at least one breach, but participants were unaware of 74% of breaches affecting them. Although some reported intention to take action, most participants believed the breach would not impact them. We also found a sizable intention-behavior gap. Participants did not follow through with their intention when they were apathetic about breaches, considered potential costs, forgot, or felt resigned about taking action.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.