A Great Man Deserves a Great Biography

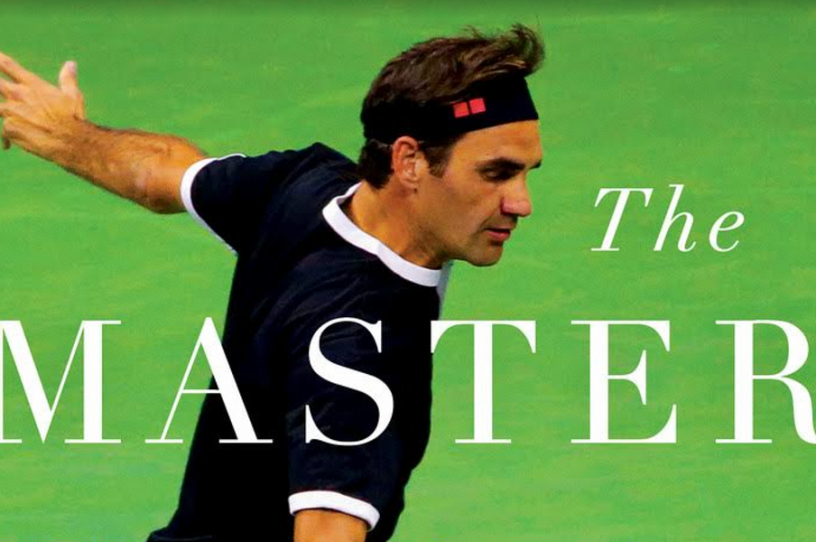

Like every other tennis writer who wants to write about Roger Federer, Christopher Clarey had a bit of a problem in writing his biography, The Master: The Long Run and Beautiful Game of Roger Federer. You see, the greatest piece ever written about Federer—indeed, arguably the greatest piece written about tennis—has already been written: It’s “Roger Federer as Religious Experience,” David Foster Wallace’s 2006 essay about the Swiss great then early in his days of domination. Nothing written about Federer since has come close to capturing the essence of the man as Wallace did his essay. Nothing probably ever will. But DFW’s piece attempted to capture Roger Federer the tennis god who does the impossible on the court. Clarey is far more interested in showcasing Federer the man: tracing his history, exploring his family dynamics and the figures who have influenced not just Federer’s game but who he is as a person.

Clarey—the New York Times’ tennis columnist—had more than enough material to pull from in assembling The Master—he’s been following tennis for a few decades, and has interviewed Federer multiple times over the course of his career. These interviews, along with the sheer breadth of other figures from Federer’s life Clarey talked to with, are the greatest strength of The Master. Clarey spoke with essentially anyone who knows anything about Federer firsthand, from rival Novak Djokovic to Madeleine Barlocher—who ran the juniors program at the first tennis club Federer played at as a child—to Federer’s childhood French tutor. It gives a comprehensive picture of Federer from his days as a petulant child to composed tennis icon, with greater detail about Federer’s life than has been assembled to this point. Even longtime Federer fans will learn new things about their hero in reading Clarey’s book.

As interesting as the history Clarey assembles is, and even with all the insight he’s able to draw out from his interviewees, The Master fails at what Federer is best known for: style. While most of the book is a straightforward biography, Clarey falls prey to a classic temptation in writing celebrity biographies, and repeatedly inserts himself in the story. We hear about how tennis was one of the few constants in his life as a Navy brat, about his collegiate tennis career, and his thoughts on the Wilson Pro Staff 85 racquet. But this isn’t a first-person narrative; the self-references are too few to seem like a normal part of the biography, making their appearances always seem oddly out of place.

For all the deep research that undoubtedly went into the book, at times Clarey gives the impression at times that he’s just padding the word count and trying to elevate his prose, both by forcing himself into the narrative and with his occasional bizarre attempts at stylistic flourishes. (The weirdest one: “Nadal is still far too young to be thinking about a tombstone, but if he ever orders one from Amazon, that sentence should be on it.”)

These shortcomings aren’t enough to detract from The Master’s appeal to Federer aficionados. But they certainly don’t make the book any more engaging, and for the uninitiated they undoubtedly make the 406 pages of reading less enjoyable than anything written about the most stylish tennis player ever ought to be.

A recurring theme in the dissection of Federer’s early days is the difference between a very good tennis player and a great one. Federer, of course, elevated himself from the pack to become a great one, making it somewhat ironic that unlike its subject, The Master only ever achieves very goodness. And when writing about someone like Roger Federer, that’s just not enough.