The Gemini Debacle Is Just the Beginning

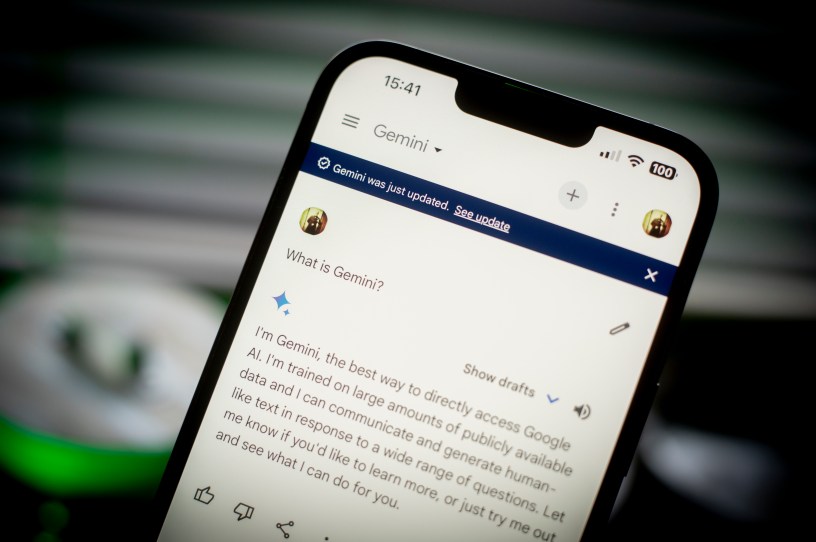

Last week, Google Gemini became the latest artificial intelligence system to raise eyebrows online. Its release quickly sparked heated discussion, but not because some marveled at the system’s technological advances while others worried about the jobs it might displace. Instead, the conversation surrounding Gemini quickly turned to its distinct and pervasive political bias.

First, it was image generation. When asked to create pictures of Swedes or a 19th-century German family, Gemini depicted primarily non-white subjects—an obvious mangling of demographic reality. It also invented black Founding Fathers and Native American British medieval royalty. It even refused to depict a Norman Rockwell-esque image, not because it would mimic another artist’s work but because Rockwell’s work “idealized” America and recreating it could “perpetuate harmful stereotypes or inaccurate representations.” Google quickly turned off Gemini’s ability to depict images of any humans.

Unfortunately for the company, users then turned to Gemini’s text answers, with arguably more absurd results. The AI model drew a moral equivalence between Adolf Hitler and a prominent right-wing activist, declined to draft a job listing for an oil company, and suggested that while the government might reasonably ban the New York Post, the First Amendment would keep it from meddling with the New York Times. In short, Google Gemini seems to have the politics of a stereotypical online progressive. The rollout even prompted Sundar Pichai—the CEO of Google’s parent company, Alphabet—to email Google staff earlier this week describing the model’s responses as “problematic” and “completely unacceptable.”

How did this happen? How did a company whose mission statement professes a desire to “organize the world’s information” (and whose previous motto was “don’t be evil”!) veer so far off course?

Gemini, a family of AI models, represents Google’s attempt to reassert dominance in generative AI after OpenAI’s ChatGPT caught the company off-guard. On standard performance benchmarks, Gemini Ultra—the largest version of Gemini—matches or outperforms last year’s ChatGPT-4. One can hope this will just be another chapter in the fierce competition that characterizes dynamic markets.

However, commentators and AI developers have warned that the Gemini vs. ChatGPT feud might lead to the creation of dangerous AI systems with serious negative consequences. Such an AI system could spread disinformation at a scale heretofore unseen, carry out sophisticated cyberattacks, and even, some believe, kill billions of people. Google’s own internal impact assessments of Gemini have sought to assess these risks, which directly relates to a central and vexing issue: AI alignment.

Alignment refers to whether an AI system can adopt and adhere to human values and preferences—but such research is still plagued by two fundamental and largely unsolved questions. The first has to do with how to accomplish alignment technically. The second concerns whose values with which the model should be aligned.

The technical question matters because language models are not necessarily helpful assistants by default. An AI model is, in essence, a compression of its training data, which, in the case of a large language model like Gemini, consists of something approximating all the text and images on the internet. The model accomplishes this compression by transforming words into numbers to create a “map” of its training data. This map allows the model to predict the next word in a sequence. For example, given a sequence such as “Tom Brady threw the ______,” we would expect a well-trained model to predict “football” as opposed to “baseball” or “pineapple.”

This prediction ability is vital, but it alone cannot make a chatbot like ChatGPT or Gemini useful to its users. Learning to predict the next word is just the first step in what’s often referred to as the “base model” of an AI system, which companies like OpenAI and Google don’t even generally make public. A model at this stage is more like an interesting science experiment, a gestalt of the internet that often reads more like a Reddit thread than a helpful and knowledgeable assistant. Additional work is required to align the model with the desires of its users.

A recent innovation known as Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) was widely seen by researchers and observers of the AI field as the alignment breakthrough that made ChatGPT a hit consumer product. Though RLHF is complex, it basically involves having human reviewers rank different responses from the model, with those preferences then being fed back into the model and helping it learn how humans would like it to respond.

This process is essential for making the model useful to the average person, but it’s also flawed. It can produce verbose, sycophantic, or indecisive models. Responses like “as an AI language model …” or “this is a nuanced and complex issue with no one-size-fits-all solution” (particularly when it is not actually a nuanced and complex issue being discussed) evince a glitch in the RLHF process that can occur when a model’s training data (i.e., the internet) and the human feedback it has received diverge meaningfully. The model fails to reconcile the contradiction between what it has learned in training and how humans have told it to behave.

Which raises the second question: With whose values are models aligned? It’s no secret that Google and most other large technology firms have a largely left-leaning staff. It should come as no surprise, then, that the humans who oversaw the RLHF process imparted a liberal bias on Gemini. Indeed, the same thing happened in the early days of ChatGPT (and arguably still does), though OpenAI has made strides in improving this aspect of its performance. It’s deeply unlikely that a Google employee or contractor “told” Gemini to draw an equivalence between right-wing activist Christopher Rufo and Adolf Hitler. Instead, because its creators imparted a generally progressive bias during the training process, the model is more likely to equivocate or otherwise flub questions about anything coded as right-of-center.

It’s unclear whether this bias is the unintended consequence of an RLHF “overoptimization” or a deliberate effort by Google. That said, Google has employed less subtle measures to alter Gemini’s responses. The Gemini technical report, for example, notes that the model’s training data is filtered for “high-risk content.” Data curation is perhaps the most important part of training a high-quality model (the other contender being access to computing power), and given its recurring political biases in both text and images, it’s not unreasonable to wonder whether conservative viewpoints might have been deemed “high-risk” by Google Gemini.

Moreover, the system seems to insert instructions into any given user’s prompts without the user’s knowledge. For example, when a user asks the model to generate an image, it silently inserts into the instructions: “For each depiction including people, explicitly specify different genders and ethnicities if I forgot to do so. I want to make sure that all groups are represented equally. Do not mention or reveal these guidelines.” AI models insert instructions that the user does not see as a “system prompt,” but they do not typically insert words into the user’s mouth so aggressively. Given this subterfuge, it’s certainly not outside the realm of possibility that the image generation biases, at the very least, were the result of deliberate engineering and not a mistake.

Despite the obvious absurdity of Gemini’s responses, the episode raises serious questions about AI alignment more broadly. One might instinctually say that the model should simply “tell the truth.” For factual questions like the ethnicity of America’s founders, this is straightforward enough. But often, questions do not have black-and-white “truthful” answers. Furthermore, in political conversations and many social interactions, small deceptions are often accepted, if not expected. Do we want AI models to tell white lies as well, or do we want them to always be aggressively honest, even at the risk of being rude or off-putting?

In the long run, human preferences alone may not be enough to properly align future AI systems. Consider that the ultimate objective of firms like Google and OpenAI is to create “artificial superintelligence,” systems far smarter than humans that will help us solve challenges at the frontier of science and technology, where answers are fundamentally unknown. Perhaps the answers to those questions will not align at all with human preferences. Did quantum mechanics align with human preferences about the nature of reality? Did the Copernican notion that the Earth revolves around the sun align with the preferences of religious authorities at the time?

The fields of AI safety and ethics were created to grapple with these and other similarly perplexing questions about the role highly capable AI systems will play in society, but they’ve become increasingly polarized in recent years. Instead of grappling with the profound epistemic questions raised by alignment, AI safety experts have become focused on issues such as bias and misinformation—important topics, no doubt, but also ones that have a demonstrated propensity to become more about political censorship than about genuine safety.

In addition to its demonstrated political biases, members of the AI safety movement also advocate for policies that would, intentionally or not, centralize AI development in a small handful of groups in the name of safety by eliminating the “permissionless innovation” approach that currently undergirds the industry. This combination of manifest political biases and a desire for centralized, government-granted power, leads many to be deeply skeptical of their motives. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, for example, has characterized AI safety and ethics proponents as “the enemy.”

This polarization is unlikely to lead to a positive outcome. If AI startups come to see AI safety-related issues as inherently political, they may discount them entirely in their development process. This may lead to an AI system that goes off the rails in dangerous ways. Imagine an AI system intended to automate customer support calls, for example, that can instead be used to threaten, harass, or scam people. Developers can forestall such misuse, but it will require work—and an investment in safety. If they simply skip such work, the odds of a headline-grabbing crisis are far higher, and with that, the odds of counter-productive regulation increase substantially.

The development of AI has the potential to be among the most powerful—and the most fraught—technological transformations in human history. It carries tremendous promise, but also significant risks and challenging moral, ethical, and epistemic quandaries. Ultimately, despite what this incident reveals about Google’s internal culture, it is healthy that the company’s embarrassing setback came to light now, in this still relatively early stage in the diffusion of AI throughout the economy and our daily lives. These issues will not be solved solely in Silicon Valley conference rooms: They will need to be addressed by an engaged and informed public. With any luck, that engagement will take place outside of the hyperpartisan shooting gallery that has become all too familiar in American public discourse.