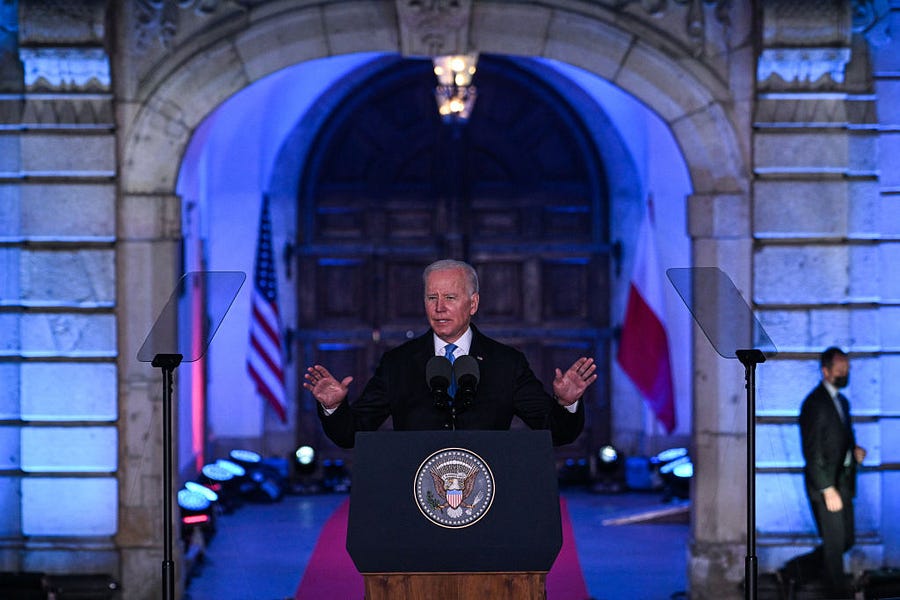

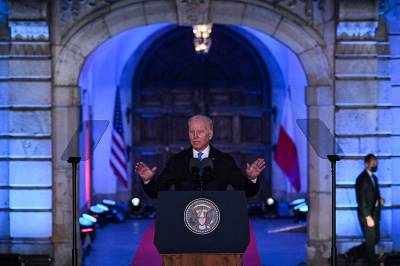

President Biden’s apparent off-the-cuff comment about Vladimir Putin in his speech Saturday in Warsaw—“For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power”—was hardly just an ad-lib moment: He not only was speaking the truth morally, but the president was also stating the obvious strategically. There can be no peace if the ambitious, revanchist, mafia-like Don Putin remains in charge in the Kremlin. Already he’s invaded Georgia, Ukraine twice, and he’s intervened in both the Syrian and Libyan civil wars—none of which has been done other than to advance his imperial Russian designs. Toss in the assassinations in Russia and abroad of Putin’s designated enemies, the assault on Russian civil liberties, and his authorization of government and private Russian cyberattacks on the West and it is impossible to imagine either real peace or real stability with Putin in power.

Yet it didn’t take but a Washington nanosecond for the White House to walk back Biden’s comment. “The president’s point was that Putin cannot be allowed to exercise power over his neighbors or the region,” an unidentified official said. “He was not discussing Putin’s power in Russia, or regime change.” On Sunday, Secretary of State Antony Blinken reiterated the point on television, saying that the administration was not in the business of pursuing “a strategy of regime change” in Moscow.

This walk-back makes it look like the president is not in command of his own policy—a look not at all helpful for someone sitting behind the desk in the Oval Office. Nevertheless, one can understand why officials thought explaining away Biden’s remark was necessary. First is the calculation that even suggesting the possibility of regime change evokes all kinds of bad political vibes post Iraq and Afghanistan. Second is the reality that because the United States and NATO have publicly waved off any intent to intervene directly in the war in Ukraine, it’s unlikely that there could be the kind of sweeping, decisive victory over the Russian forces that might lead to a demand that Putin step down or generate a palace coup in Moscow. Third, if that is the case, the reality is that Kyiv will be negotiating an armistice at some point with Putin still at the helm.

Nevertheless, Biden’s ad-lib was not the verbal blunder that the president is sometimes given to; it followed logically from the speech itself. As Biden pointedly noted in the speech, “the United States and NATO worked for months to engage Russia to avert war. … Time and again, we offered real diplomacy and concrete proposals to strengthen European security, enhance transparency, build confidence on all sides. But Putin and Russia met each of the proposals with disinterest in any negotiation, with lies and ultimatums.” The fact was, the president concluded, Putin “was bent on violence from the start.” By Biden’s own account of Putin, there can be no real peace for Ukraine and no peace of mind for Eastern Europe if he remains in power.

The prospect of Putin remaining in power and the reality of settling for an armistice of some kind can’t help but bring back memories of the Korean War and the aftermath of the Persian Gulf War—both wars that resulted in something short of victory over the despots residing in Pyongyang and Baghdad. The “peace” that followed was dependent, in the first instance, on an American military commitment that has now lasted for seven decades and, in the second instance, on a decade of no-fly zones, an occasional military strike, and on a substantial commitment of forces and support to partner states in the region. None of these was unreasonable considering Washington’s decision in both instances not to pursue a more comprehensive victory, although far more costly in time and commitment than originally anyone thought would be the case.

The point is, if we are indeed headed toward some form of armistice or frozen conflict in Ukraine, in which Washington and Brussels suggest Kyiv accept this as the best that can be had, it is doubtful that Ukraine’s government could accept just any deal with the Kremlin. Nor should it unless given concrete assurances from Washington and allies that Ukraine will be given considerably more military assistance and a guarantee that it will have the West’s backing if an agreement is reached. A Minsk III, in which Paris and Berlin pretend to be serious about a settlement and has no punch behind it, is not in the cards. As Biden himself noted in Warsaw, Putin is not a man of his word. And Ukrainians know (and have apparently included in their terms for negotiating a deal) that absent such assurances any agreement, especially one that is in any way favorable to them, will mean facing an even angrier and even more resentful Putin.

Moreover, Biden’s off-the-cuff remark—however honest an assessment—can’t help but fuel Putin’s propaganda argument that, yes, indeed, the U.S. and NATO have always had it out for him. Whether he believes that or not, it will give further legitimacy to seeing a democratic Ukraine leaning inevitably west as a threat to be dealt with, if not tomorrow, certainly in due course.

In short, while the White House predictably walked away from Biden’s ad-lib that Putin “cannot stay in power,” the reality is that the administration will not so easily walk away from the difficulties of Putin remaining in power. There is a short-term advantage to avoiding talk of regime change but there is no getting around the longer-term costs for doing so.

Gary Schmitt is a resident scholar in strategic studies and American institutions at the American Enterprise Institute.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.