The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ October JOLTS report (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) continues to make for some of the most interesting reading in bureaucratic Washington, D.C. The labor market remains unusually turbulent with surfing competition-sized waves of unfilled jobs inundating low-lying areas of available workers and gale-force levels of job quits just to keep it interesting. Like meteorologists watching as tropical depressions become hurricanes, jobs data junkies are tracking the nation’s employment market with equal parts awe, curiosity, and unease.

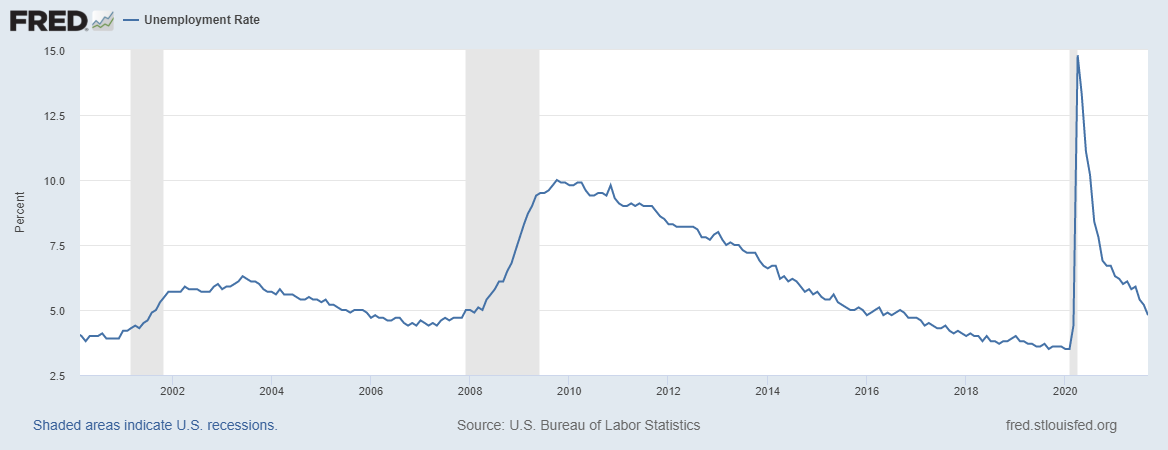

As illustrated below, the U.S. began to emerge from the COVID-19-induced economic recession in May 2020. Unemployment plunged rapidly through last summer and into the fall. Since then, the rate of decline in unemployment has moderated while job openings remain very high, leaving a ratio of 0.8 workers for every available job. If we were magically able to match every available worker to an available job, we’d still be roughly 2 million workers short.

So, what’s going on? No single factor fully explains the misalignment between workers and the job market but there are several major influences that contribute.

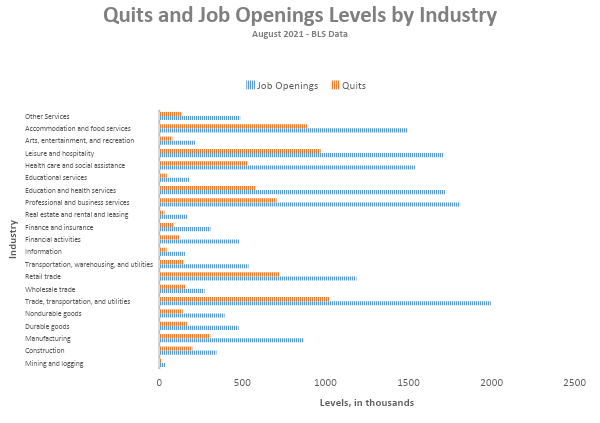

The first and most obvious is the historically high rate of job “quits.” The most recent JOLTS survey shows that close to 4.5 million people—almost 3 percent of the entire workforce and a number larger than the population of the city of Los Angeles—left their jobs in August 2021. Many are leaving in search of positions with better pay and benefits or that offer more flexible working arrangements like remote or hybrid (two days at home, three in the office) schedules. After years firmly under the thumb of employers in terms of wages and working conditions, it’s hard to blame people for trying to make the most of this window of opportunity.

There’s a catch, though. Most of the openings in the economy are in the same sectors (like service and hospitality) that people are leaving. Unless these footloose workers suddenly acquire new skills to make them viable in other industries they might very well find themselves back in the same or similar job at a slightly higher rate of pay.

Another major factor driving the labor shortage is the continuing decline in the labor force participation rate, the ratio of the number of workers in the labor market and the total available working-age population. The U.S. rate has been drifting downward for decades as the population has aged. Men, especially those with less education, have been leaving work in droves due, in part, to shrinking opportunities in the traditionally male-dominated fields like manufacturing. Now it’s women, who were a majority of the workforce in March 2020 but are currently less than half of all workers. Many have been pushed out of the workforce over fears of COVID-19 and the virus’s impact on daycares and schools that left them without care options for their kids.

Early retirements are also a factor in shrinking the labor pool. Unlike the Great Recession of 2008-10, which hit stock prices—and therefore retirement accounts—hard and forced some workers to extend their careers, stocks remained buoyant during the COVID-19 recession. Those fattened 401(k)s and IRAs have enabled some who were near retirement to leave the labor market prematurely. Other, less financially well-prepared, workers left the workforce after losing their jobs to the pandemic and, not seeing a clear path back to the labor market, hung up their cleats.

Then there’s the perennial problem of the “skills gap.” Year in and year out, in good economic times and bad, millions of jobs go unfilled because American workers lack the necessary skills. One 2020 study found that in computer-related fields, the U.S. had 1.36 million job openings but logged only 177,000 unemployed workers with computer and math backgrounds. At the other end of the labor market, skilled trades like plumbers, roofers, and carpenters are also left with chronic application shortages. Starting wages for these jobs, however, hover around $16 per hour—not much above what these workers can pick up in the service sector (where, by the way, the spike in wages has rendered obsolete the campaign for a $15 an hour minimum wage.) These are not easy jobs. They are physically demanding, borderline artisanal in skill levels, and frequently more hazardous for the same amount of money. That’s a tough sell and helps explain why so many students opt out of skilled trades.

Last, but in my view probably the most important factor in our labor mismatch, is the other, less talked about skills gap, namely the shortage of noncognitive or soft skills. Employers frequently complain about the shortage of workers with the critical thinking, teamwork, and communications skills needed for an economy that is increasingly driven by tasks that require extensive collaboration among workers. If you think it’s hard to train IT professionals, try training workers who have never learned the interpersonal skills of working and getting along with others. Noncognitive skills accumulate slowly over time beginning in infancy and develop through family, schools, and other community institutions. Those soccer leagues for 5-year-olds your kids belong to? That’s workforce preparation writ small – and adorable.

These human skills are just not as amenable to structured curriculums and classroom teaching. Moreover, they are critically necessary to the ability to learn itself. A worker without soft skills is very likely to be a worker with hard-skill deficits, too, and diminished capacity to succeed in education and training programs. It is a long, complicated path to fixing the noncognitive skills problem, which is one of the reasons many business and government leaders tend to clear their throats and stare thoughtfully at the sky when the topic comes up.

What strikes me most about our labor market turmoil is how it is embedded within the tangle of economic pathologies we’re facing as the post-COVID era begins. Congestion at our ports? Staffing. Slow Amazon deliveries and Christmas tree shortages? Staffing. Can’t get a drink at the bar, the sheets changed on your hotel bed, or a burger delivered in less than 20 minutes? Staffing, staffing, and staffing—and not just the quantity of workers but the quality of them, too. All of which adds up to economic friction, delays, and inflation that we just aren’t accustomed to. Turns out we have a lot more “essential workers” than we imagined. In fact, it looks like all workers are essential.

Somehow while riding the extraordinary tech-driven wave of the past 10 years, we’ve forgotten the economy isn’t an abstract concept but the product of billions of decisions and actions taken by people that through some magic delivers what we need when we need it at a price we will pay. The “invisible hand”, indeed. As we prioritize policy solutions to get our economy back on track, it might be helpful to revisit Lincoln: “Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.”

Brent Orrell is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.