Dear Capitolisters,

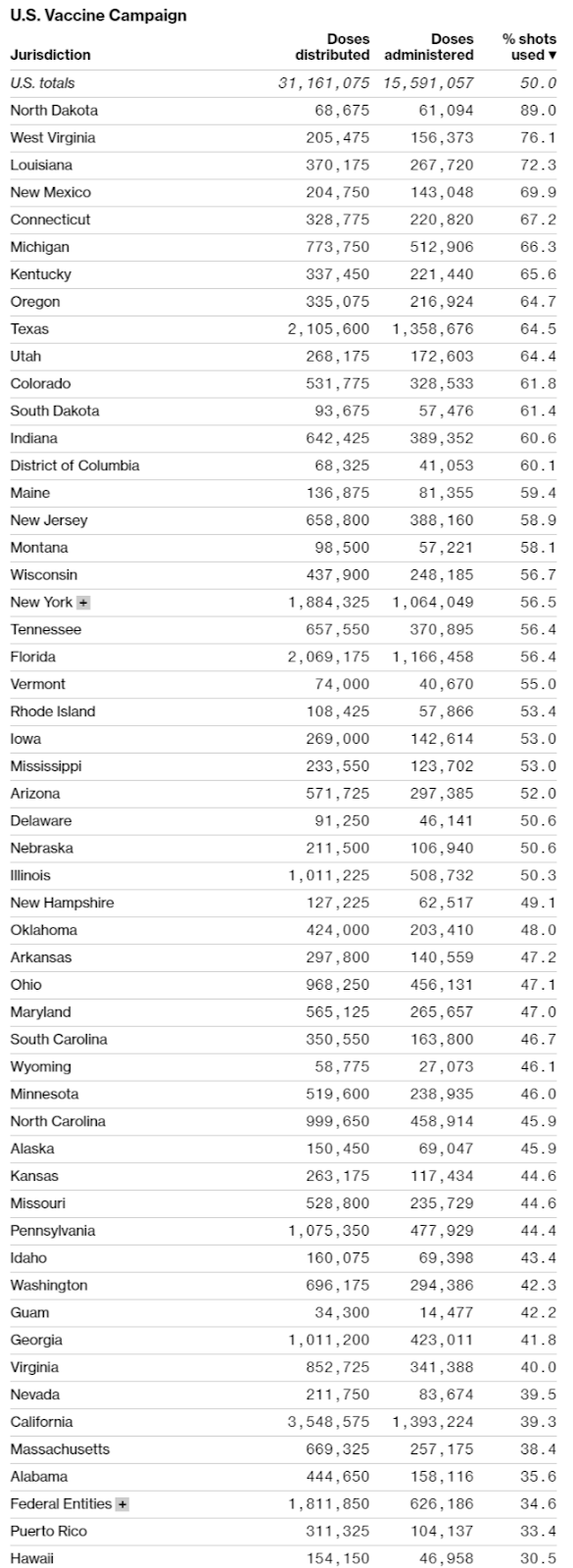

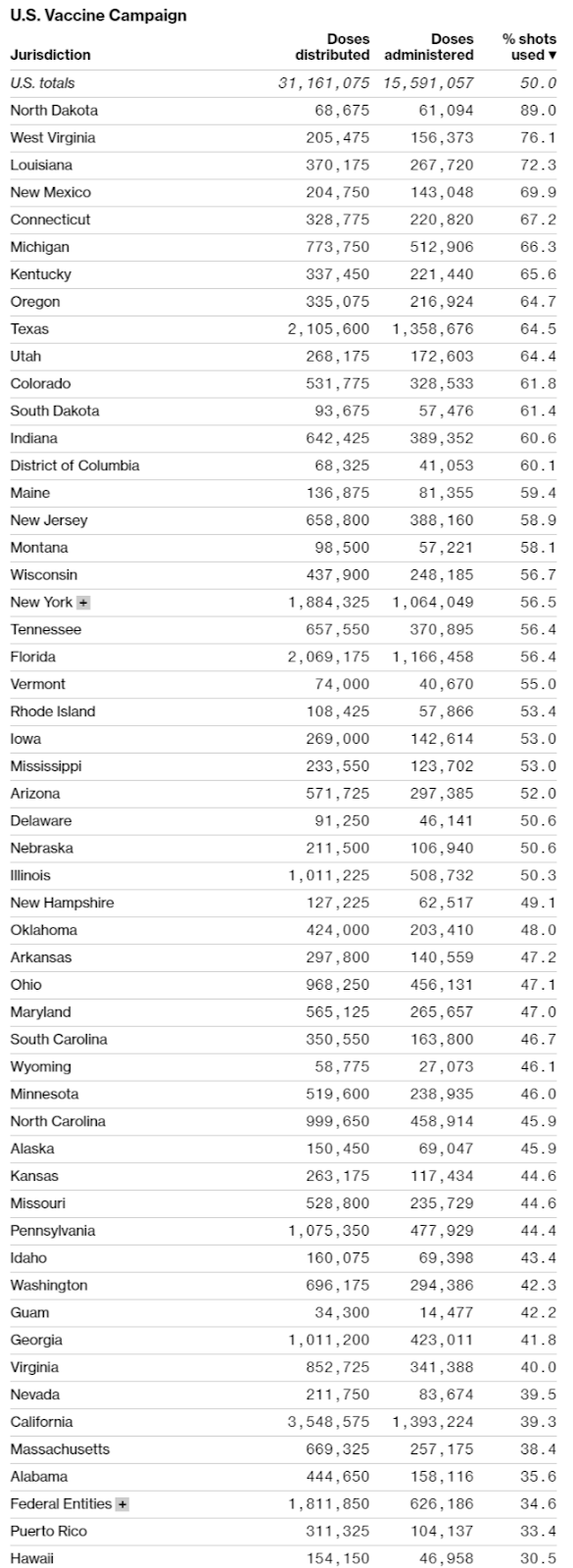

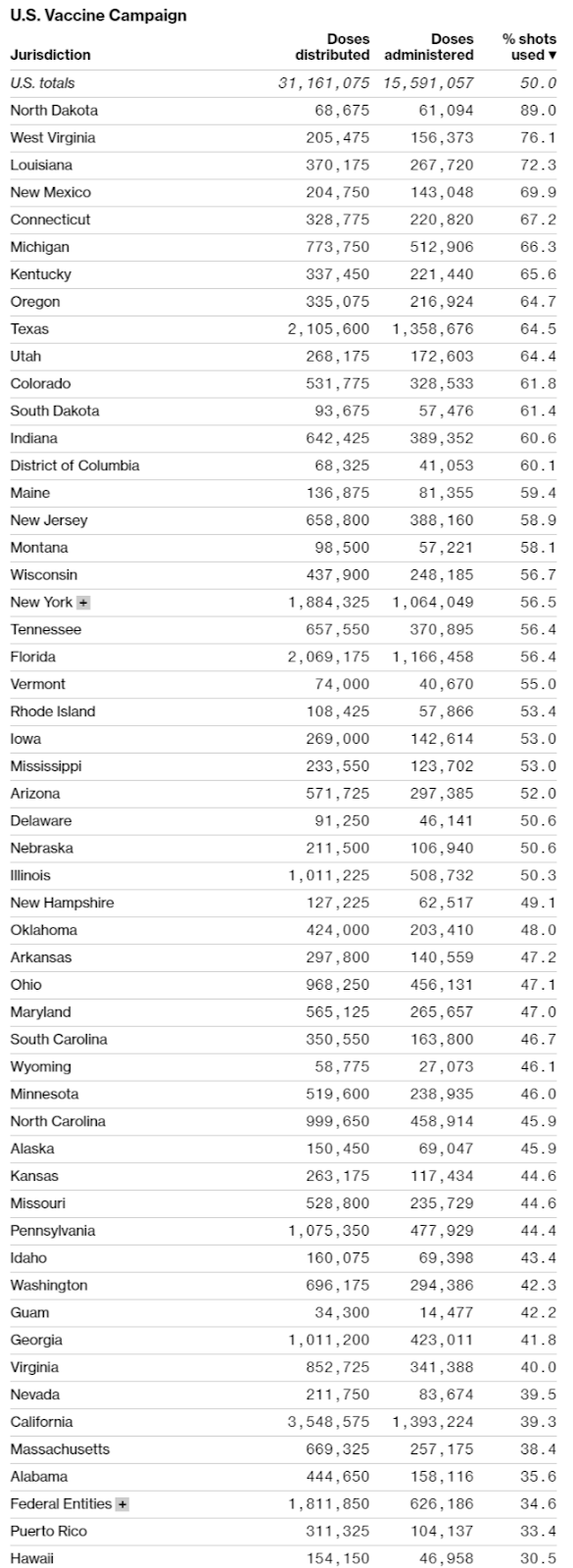

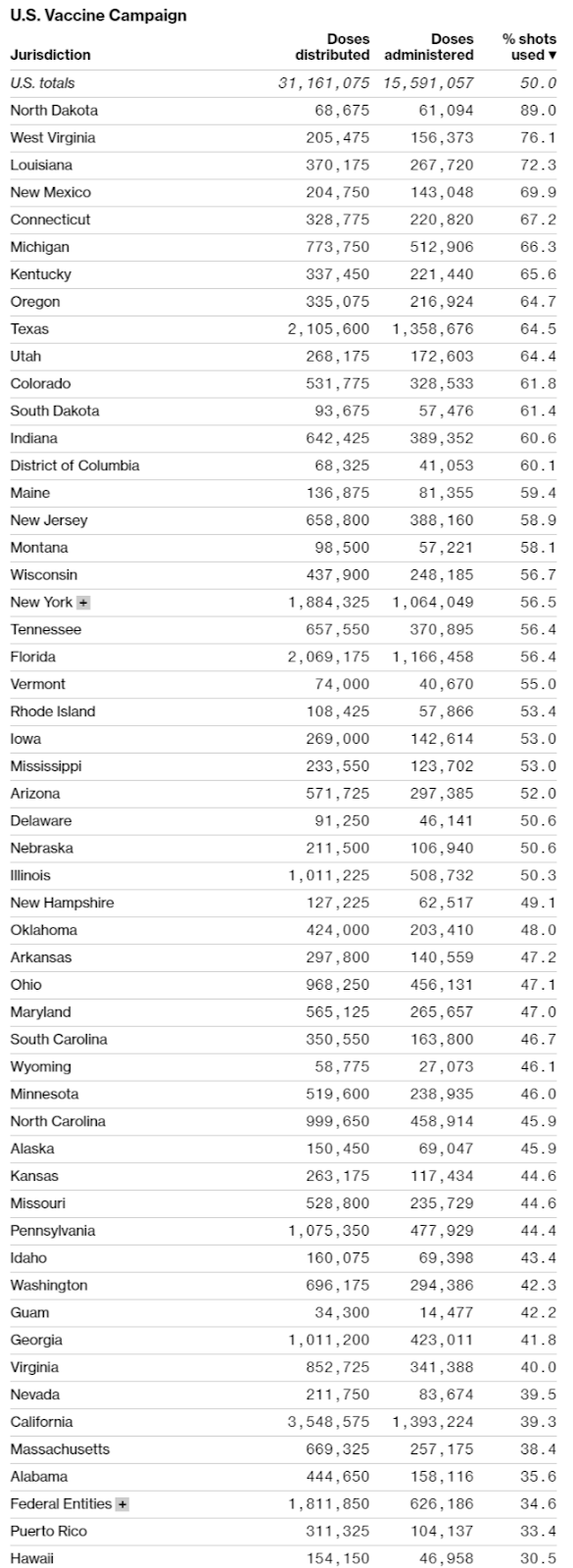

As I’m sure you’ve noticed, the United States is struggling to distribute millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses, even as the virus continues to rage across the country. Although we’ve now administered about 15.6 million doses so far, the overall percentage of delivered doses administered (50 percent) and percentage of total U.S. population vaccinated (4.75 percent) are significantly lower than where we thought we’d be at this point—more than a month after both the BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were approved by the FDA, and more than two months since the companies’ published Phase III clinical trial data showing both to be safe and highly effective. As a result, public frustration is growing, finger-pointing (feds at states, states at feds, feds at other feds, doctors at everyone) has begun, and many are questioning the U.S. approach.

It’s a pretty big mess, but one that provides some teachable moments. So that’s what we’ll try to examine today.

Where We Are Right Now

Before we get to that, however, let’s provide a brief overview of where things stand:

-

As already noted, two vaccines—BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna—have been approved for emergency use in the United States and are currently being injected in arms across the country. Outside the U.S., the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine was approved for use in the U.K. on December 30 and has since been approved in Mexico, India, Argentina, Pakistan, and a few other countries. However, it’s been reportedly delayed in the U.S. until at least mid-April due to some questions surrounding its initial clinical trials. The last big candidate on the near-term horizon is Johnson & Johnson’s single-shot vaccine, which just reported impressive preliminary results and is currently expected to seek FDA authorization in February. All but J&J were designed to be two-dose vaccines, but various data show them all to be pretty effective after one dose, leading governments—including ours—to shift their focus and inject “first doses first” instead of holding back second doses for returning patients.

-

Even though only two vaccines have been approved in the United States, all four are currently being manufactured here and abroad to speed up the vaccination process once the doses receive emergency approval. BioNTech/Pfizer in late December doubled their U.S. purchase agreement—from 100 million to 200 million doses—and recently announced a plan to double overall 2021 production to 2 billion doses. Moderna can’t match that scale but still expects to make 600 million doses this year, 200 million of which will be purchased by the U.S. government. AstraZeneca reportedly has production capacity for 3 billion doses in 2021, selling 300 million to the U.S. (if it’s ever approved!). The laggard, unfortunately, is the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine: After initially promising 12 million doses by end-February and 100 million by end-June, the company just announced that manufacturing hiccups have trimmed those targets (though the company may be able to catch up by April or May).

-

Although vaccine producers do face some challenges (especially regarding raw materials and “fill and finish” things like vials and stoppers), the United States’ real problem at the moment is distribution, not production. As helpfully summarized by Bloomberg in the charts below, data from the CDC and state health departments show that progress—measured as a percentage of doses administered versus doses received—has been wildly uneven across states, and millions of doses are still sitting around in freezers instead of being put in arms.

Making things worse is that confusion and a lack of transparency are prevalent across states, and many “leftover” doses are even being thrown out. Not good.

Now, certainly things aren’t all bad: We’ve administered the most doses in the world and trail only Israel, the UAE, Bahrain, and the U.K. in the vaccinated share of national population:

It also appears that public reluctance to get vaccinated—once thought to be the biggest threat to our return to normalcy—has dropped significantly since shots started being administered last month.

Finally, our rate of vaccination has improved a lot since December, but after topping out at about 900,000 doses per day it’s actually down a bit now:

This decline is probably due to the holiday weekend, but that’s part of the problem: In many places, the sense of urgency is seriously lacking. As George Mason University economist Alex Tabarrok noted, “we vaccinate for flu at more than twice the speed we are vaccinating for COVID,” which is a far bigger health risk and literal national emergency.

None of the “good” news, moreover, changes the fact that millions of doses remain unused after being delivered to the states weeks ago; that some “priority” populations are refusing vaccines, while millions of other Americans are desperate for them; that government guidelines keep changing as an untold number of doses are being literally trashed; and that governments at all levels had months to prepare for one of the most important moments in recent U.S. history. Meanwhile, Israel has vaccinated about 30 percent of its 9 million citizens and is on pace to reach herd immunity in March, and the much-larger U.K. is also well ahead of the U.S. pace. Neither of these countries is home to the actual vaccine manufacturing facilities and the global logistics companies/facilities that deliver them. Between this and the massive taxpayer dollars that Operation Warp Speed has thrown at the vaccines, you’d think we’d have a big advantage.

We clearly don’t.

What is OWS?

But what, exactly, is OWS? Announced in mid-May, OWS was the Trump administration’s government-wide effort to “accelerate the development, manufacturing, and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics,” with the most notable goal of producing and distributing a vaccine by January 2021. In the government, OWS was primarily a partnership between the Department of Health and Human Services—including the CDC, FDA, NIH, and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA)—and the Department of Defense. This leaked chart shows OWS’s organization:

OWS partnered with (and funded) private firms for vaccine development, manufacturing, and distribution, while also accelerating “usually laborious” regulatory approvals along the way. OWS partnerships took the form of both direct funding (subsidies) and “advance purchase contracts” for finished doses—essentially guaranteeing a vaccine producer a customer (and return on investment) if/when it received regulatory approval. The Financial Times in late November provided a good rundown of OWS’s major vaccine efforts (additional technical details are here):

Pfizer and BioNTech: $2bn pre-order for 100m [now 200m] doses, if the vaccine is approved

Moderna: up to $955m investment for development, $1.5bn for manufacturing and delivery, including a pre-order for 100m doses

Johnson & Johnson: $456m investment for development, $1bn for manufacturing and delivery, including a pre-order for 100m doses

AstraZeneca and Oxford university: up to $1.2bn for development and manufacturing, including a pre-order for 300m doses

Novavax: $1.6bn for manufacturing, including a pre-order for 100m doses

Sanofi and GSK: $2bn for development and manufacturing, including a pre-order for 100m doses

The OWS home page also shows other efforts to support vaccine production, for example funding raw materials and “fill and finish” facilities across the United States.

What OWS Arguably Did Right

Although much of the public’s current focus is what went wrong with OWS and the vaccine rollout, most people tend to agree that OWS did a few things right. First, the streamlining of regulatory scrutiny—particularly under the FDA’s “emergency use authorization” system (which, for example, freed vaccine manufacturers from receiving an FDA site inspection before shipping doses)—has been lauded as instrumental in speeding up the vaccine process, which can normally take years from research to distribution. Second, the front-loading of government funds for the development of select vaccine candidates, as well as the advance purchase contracts for all producers, lowered companies’ risk of developing the vaccine and allowed some of them to ramp up manufacturing long before their vaccines were approved. Third, there have been numerous reports of the U.S. government helping pharmaceutical manufacturers obtain raw materials, other supplies, or facilities during the peak of the pandemic, which roiled domestic and foreign businesses alike. Finally, observers have generally praised OWS’s decision to outsource distribution of non-Pfizer vaccines to an experienced centralized distributor, McKesson Corporation, which distributed vaccines during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 and had a pre-existing government contract.

But But But

On the other hand, there is also evidence that OWS has bungled certain aspects of the vaccination campaign or wasn’t nearly as essential as claimed—even in some of the areas that have drawn widespread praise.

For starters, Pfizer’s willingness and ability to self-fund the development, production, and distribution of its vaccine with nothing more than a no-strings government promise to buy finished, approved doses—a deal that came months after the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine was developed—raises questions about the need for government pre-funding at all. (The companies actually predicted in April 2020 that they’d have millions of doses ready by year end.) Surely, the U.S. government agreement—and others like it—helped defray Pfizer’s risk, but the company was going full steam ahead regardless of those commitments. These contracts might also have been more crucial for a smaller company like Moderna, though Moderna’s $50 billion market capitalization—up sixfold since early 2020—suggests the company wouldn’t have had difficulty finding private funders, either.

Just as importantly, OWS may have actually hindered vaccine production and distribution in the United States. First, as Pfizer’s CEO famously noted, full participation in OWS would have subjected the company to potential political influence and regulatory oversight that could have complicated (and in Moderna’s case, slowed down) the process of bringing a vaccine to market. Second, reports indicate that OWS impeded Pfizer’s ability to increase supply in late 2020 because certain raw materials had been earmarked for vaccine producers that participated more fully in OWS by taking upfront R&D funding. Even though several of these companies (e.g., Sanofi and Novavax) are nowhere near ready to ship a finished vaccine (despite billions in government funds), their OWS “favored status” among raw materials suppliers disadvantaged Pfizer’s access to those very same sources—a position resolved only by a subsequent U.S.-Pfizer agreement for more doses (famously rejected by the Trump administration earlier on) that freed up those inputs and allowed Pfizer to boost vaccine supply.

Finally, the OWS contracts under which the federal government purchased all vaccine supply have proven to be a key reason distribution has been so underwhelming. As Virginia Postrel explained in a recent Bloomberg column:

By guaranteeing large purchases, the federal government gave manufacturers strong incentives to produce the vaccines. It was a smart move, and it worked. But now we’re experiencing the downside. Buying up the supplies and bestowing a vaccine monopoly on state governments blocked the normal distribution channels connecting producers with vaccinators.

Whether you’re laying fiber optic cable or delivering packages, that last mile is the tricky, labor-intensive, expensive part. To reach individuals, the system has to go from centralized operations to decentralized ones. That’s why we have retailers rather than ordering our toilet paper from Georgia-Pacific, and why they, in turn, often rely on distributors. “Cutting out the middleman” is a catchy slogan, but intermediaries make the system work.

When the federal government turned state agencies into the country’s vaccine distributors, it bypassed the usual supply chains. Doctors and hospitals couldn’t get Covid-19 vaccines the way they order other inoculations.

Distribution also became politicized in ways that slow down vaccination. Every shot comes with a ton of paperwork, and the rationing rules are hard to understand. Who exactly qualifies as a health-care worker or an essential employee? Is it OK for hospitals to give shots to janitors or billing clerks?

We’re now seeing both problems—bypassing traditional distribution networks and politicized rationing rules—in real time. On the former, pharmacies with ample experience distributing vaccines have thus far had only a minor role (and in some states, no role) in distribution, and those involved can’t do much without state approval. As Walgreens’ CEO Stefano Pessina put it, “We are just an agent for the states. … We are vaccinating at a pace that is a fraction of the pace that we could be doing. We could do much more as a pharmacy chain if we had a certain degree of freedom.” Now, states are turning back to those pharmacies—or other private companies like Starbucks with longstanding expertise in logistics and distribution (plus available real estate)—for more help. However, the states still have to obtain doses from the feds, and that too has turned into a logistical nightmare.

On the latter issue, Postrel recounts numerous examples of byzantine and ever-changing state rules and requirements gumming up the works—something I recently experienced firsthand trying to figure out how to eventually get a jab here in badly lagging North Carolina. (My county alone has four different websites—one for each vaccination site!—for possible appointments, and public details are non-existent.)

The state rules weren’t developed in a vacuum and instead generally reflect the late-arriving guidance from the federal vaccine advisory panel on who should be vaccinated first (Phase 1a, 1b, etc.). It’s these federal recommendations, delayed for months amid interagency wrangling, that doctors and supply chain experts tell the Wall Street Journal has severely impeded the rollout. “If you told states your priority is to vaccinate as many people as possible as fast as they can, they would have run the campaign differently,” said one expert, “but that’s not what they were told.” As a result, “manufacturing and distribution of the first two vaccines in the U.S. … has effectively outpaced the ability of those administering the vaccines to keep up under the current guidelines to set vaccination priorities.” Hence, all those unused doses.

On the bright side, the government has since relaxed the guidelines a bit, and states have followed suit. However, because the government’s overall approach—focused on high-risk groups instead of simply maximizing needles in arms—remains in place and with more than 50 percent of distributed vaccine doses still unused, the current supply overhang should continue for weeks to come. And, of course, there are continued reports of wasted doses and other fist-clinching events that priority guidelines create—no wonder everyone in the government is anonymously blaming one another for the mess.

Finally, there are also questions about what OWS didn’t do on the regulatory front, namely accelerating its emergency approval process or providing a parallel avenue for people to take vaccines that did not yet receive government signoff. To reassure the public about the vaccines’ safety, the FDA has quite publicly attested to maintaining its standard approval process, but this approach has also caused vaccine authorizations to be a bit slower than in other places, such as the U.K.. Given the pandemic’s ongoing toll in the United States, this “drug lag” can cost numerous lives.

Just as importantly, the federal government has not allowed Americans to volunteer to receive unapproved vaccines (and, of course, waive their liability in case of a problem)—a “right to try” approach that could have been done in parallel with the standard FDA approach and might have boosted public support if few side effects were reported. As Tabarrok has noted, the AstraZeneca vaccine is effective, has been approved in several countries, has support from numerous medical professionals, and is already being produced in large volumes in a factory in Baltimore. Continued U.S. refusal to allow Americans to access it (and any other vaccines), as thousands die from COVID-19 every day, is a considerable failure.

Would Free Markets Have Done Better?

All of the above has led many people to ask whether the United States’ vaccine situation would be better today without OWS and under a “market-based” approach. Perhaps the loudest pro-market voice has been economist John Cochrane, who summarized his extensive blogging on the subject in a recent National Review piece on how the free market would have better addressed investment, testing, safety, distribution and other aspects of the vaccine process. He concludes that “[a]llowing the vaccine to go to the highest bidders—and allowing people to get it at CVS or administer it themselves — would have rolled vaccines out much faster, and to people more likely to spread the disease without the vaccine, and encouraged those who can shelter and wait to do so.” The result: an imperfect system, surely, but far fewer lives lost than under our current approach.

Contrary to what you might think, however, this conclusion is not (or at least not only!) knee-jerk libertarianism. As Cato healthy policy expert Michael Cannon noted in early December, the theoretical answer to the vaccine question isn’t an easy one, even for libertarians: “If the government could allocate vaccines in a way that gets more of them to the highest‐value recipients than market forces would, then that would be a case of government doing what even libertarians want it to do: using its coercive power to stop individuals from violently (if unintentionally) assaulting each other.” After subsequently seeing the vaccine rollout, however, Cannon sided firmly with the market:

Would market prices guarantee that vaccines would go to the highest‐value recipients first? Not at all. But market allocation doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to outperform the alternative of government rationing….

Government rationing is detracting from the good that market forces would do, and slowing the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, by diminishing the incentives for speed and security on the part of manufacturers and retailers. In many cases, it is resulting in low‐value recipients receiving vaccinations before high‐valued recipients do. It is diminishing the incentives for manufacturers to accelerate production. And in some cases it is costing lives by allowing vaccines to spoil.

Other economists, such as Cato’s Ryan Bourne and George Mason’s Scott Sumner, offer additional support for the argument, again citing not only the theory but also the actual mess we now have—especially regarding the inevitably politicized prioritization system and its resulting inefficiency and waste.

Summing It All Up

So, would we have been better off without OWS and a more market-based approach? On the one hand, I think some of the criticisms and hypotheticals raised by OWS critics are a bit nitpicky or unrealistic. It seems to me unlikely, for example, that Pfizer or Moderna really could have been jabbing millions of arms in late spring or early summer, simply due to production technicalities, resource constraints, and logistical hurdles (e.g., the Pfizer vaccine’s need for extreme cold storage). I also think that a “pure” market-based approach that simply auctioned off doses to the highest bidders and let anyone get an untested jab, while theoretically more effective in encouraging production and distribution (and thus in eliminating the virus), would probably raise quite real and serious political and psychological considerations, potentially turning people against the vaccine or creating even more populist hostility and tension. (If you think, correctly, that media coverage of vaccine complications is bad now, just imagine what it’d have been in a “laissez faire” system!) Because getting everyone to take the vaccine is the goal (and given the current political moment), these considerations must be taken into account and, I think, complicate the free market conclusion.

On the other hand, it’s rarely a good bet to underestimate the ability of markets and sellers to adapt quickly to satisfy consumer demand. Where there’s a will (and a dollar), there’s usually a way. Furthermore, the OWS approach has created some obvious problems in terms of production and, more importantly, distribution—problems that, as Pfizer’s mostly government-free approach and other nations’ speedier distribution demonstrate, were both unnecessary and costly. Some of those issues could, in fact, be impossible to avoid in a system run not by producers and consumers but by political appointees who inevitably consider public relations, influence, career advancement, partisanship and other non-market factors when deciding who gets the vaccine in what order and how to justify it.

Unfortunately, with most 2021 vaccine doses having been purchased by governments, it seems unlikely that a radical, “free market” vaccine solution will be emerging any time soon. That said, there are certainly some steps that the federal and state governments can take now—based on what’s worked in certain states and countries like Israel—to improve what we already have: for example, eliminating or reforming the priority system bureaucracy for the majority of remaining and future doses, decentralizing vaccine distribution points, and ensuring that no doses go to waste—even if it means pulling in the pizza guy off the street. Some of this already appears to be sinking in, but—as the state numbers now show and as the new “U.K. variant” gains steam—it’s absolutely essential that we speed up things even more.

The vaccine rollout might also provide some broader lessons regarding the role of government in economic policy. Here, one can argue what “worked” was basic government funding for research (for example the NIH’s early-stage support for Moderna and BioNTech’s mRNA technology long before COVID-19 existed); no-strings rewards—whether purchase contracts or something similar like prizes—for delivering a requested product or service; a streamlined regulatory regime; and, of course, openness to global knowledge, capital, labor, and materials. What came up short, on the other hand, was regulatory inflexibility and extensive meddling in—if not attempted rewiring of—complex manufacturing and distribution supply chains that have evolved over decades based on millions of interactions between suppliers and their customers.

Given President-elect Biden’s promise to “fix” the vaccine situation via even more top-down supply chain mandates, we might need these lessons even sooner than we think.

Chart of the Week

Stop the virus, start the economy (source)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.