Happy Friday! And best of luck to Morning Dispatcher Sarah who is officially birthing her “Lil Brisket” later today!

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

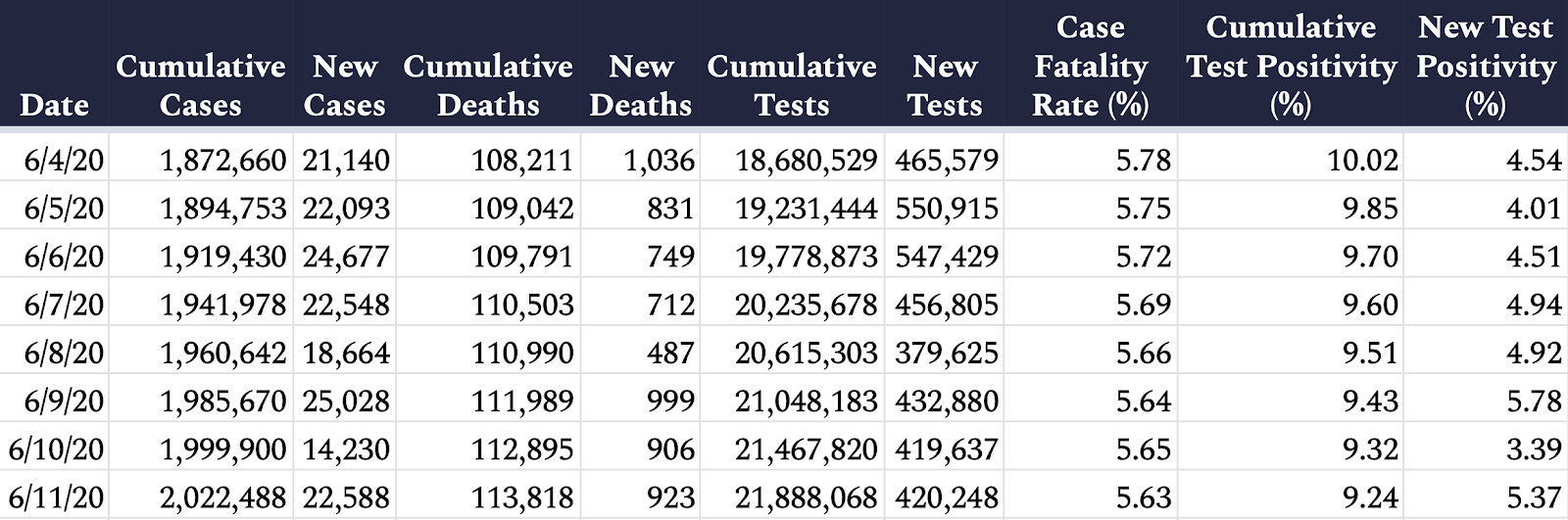

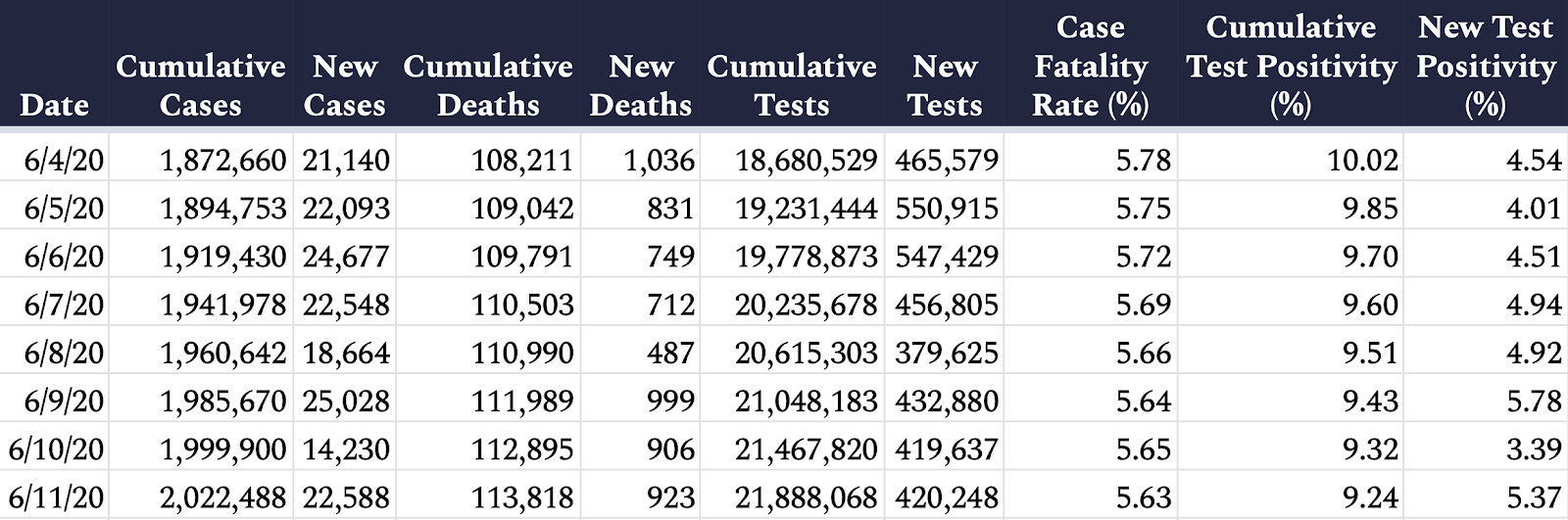

As of Thursday night, 2,022,488 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States (an increase of 22,588 from yesterday) and 113,818 deaths have been attributed to the virus (an increase of 923 from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 5.6 percent (the true mortality rate is likely much lower, between 0.4 percent and 1.4 percent, but it’s impossible to determine precisely due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 21,888,068 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States (420,248 conducted since yesterday), 9.2 percent have come back positive.

Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley apologized for his role in President Trump’s walk across Lafayette Square last week for a photo op after protesters were relocated with rubber bullets and tear gas. “I should not have been there,” Milley said. “My presence in that moment and in that environment created a perception of the military involved in domestic politics.”

1.5 million Americans filed for unemployment insurance last week, the fewest since the coronavirus crisis began in earnest 12 weeks ago, but still a historically high number.

Twitter reported via blog post yesterday it had identified and deleted more than 150,000 Chinese government-linked accounts that were spreading misinformation about Hong Kong protesters and China’s response to the coronavirus. In the same post, Twitter also announced the removal of accounts associated with Russia and Turkey responsible for spreading state-sponsored propaganda about their respective governments.

The video-conferencing platform Zoom admitted to suspending the accounts of activists in the United States and Hong Kong at the behest of the Chinese government for coordinating events in remembrance of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

A Setback for the Surveillance State

Nearly three weeks of nationwide protests following the death of George Floyd have unleashed a stupendous amount of political energy in America. It’s still unclear exactly what forms of concrete change that energy will settle into as it cools, but things are undeniably on the move. At the federal level, Democrats and Republicans are already pushing competing police reform packages in the House and Senate, jockeying over the names of military bases and legal doctrines like qualified immunity. Across the country, many states and local jurisdictions are beginning to revamp their own law enforcement policies and procedures.

But one major change that is likely to dramatically affect the future of policing in America has already quietly taken place this week. A number of major tech companies have announced they will not sell facial-recognition technology to police departments until the use of that technology is regulated at the federal level.

Earlier this week, IBM and Amazon both took the plunge; yesterday, Microsoft followed suit, with company President Brad Smith calling for a “national law in place, grounded in human rights,” to govern the use of facial recognition software. “The bottom line for us,” he said, “is to protect the human rights of people as this technology is deployed.”

As we’ve discussed in this newsletter several times before, one of the most unsettling long-term tech trends of recent years has been the growing symbiosis of private-sector surveillance tech with both federal and local law enforcement agencies, an arrangement that has grown more ominous as that technology has increased in power.

It’s no surprise facial recognition technology has come under heavy scrutiny during a time of anti-racism protests: A number of studies have shown that the recognition algorithms currently in use are far more likely to misidentify nonwhite people than white people, raising concerns that their use could lead to misidentifications that run the risk of turning deadly.

“One of the most dispiriting things of looking at law enforcement these days is revelations of how often police actually do make contact with, especially, black Americans,” Matthew Feeney, director of the libertarian Cato Institute’s Project on Emerging Technologies, tells The Dispatch. “The issue here with the deployment of facial recognition is that you would potentially increase the instances where law-abiding people are stopped by the police. And those can potentially be very confrontational if not deadly meetings. So I think that’s a significant concern.”

Nor are the ethnic imbalances of imperfect algorithms the only danger of such technology being used by law enforcement. Even a program without such imbalances would still pose real civil liberties concerns.

Current technology already gives police incredible reach when it comes to identifying anybody anywhere who catches their eye. If you’ve ever been arrested, your likeness is already likely sitting in a database that law enforcement can use to identify you from social media, security footage of places you’ve been, or a picture they take themselves. Your record’s squeaky clean? It may not matter: According to the Electronic Frontiers Foundation, more than half of U.S. states permit law enforcement to query their driver license databases for facial recognition purposes.

At least this requires an officer to take an active interest in you. But with the advent of the “internet of things,” even that might not be necessary: Picture a regime where an officer’s always-on body camera constantly takes note of every face it comes across and indexes it in real time against a database of persons with outstanding warrants. That might sound like the stuff of dystopian fiction, but the technology to implement it is years, not decades, away.

All of which is to say that if legislators at every level want to head that scenario off, there’s no time like the present to get started.

“If you think of a lot of the most prominent shootings or killings that we’ve seen on camera at the hands of police, Eric Garner was selling fraudulent cigarettes, George Floyd tried to use a fake $20 bill, Walter Scott was behind on child support payments,” Feeney said. “They’re infractions for sure, but they’re not a threat to the physical safety of anyone. … If there’s something that’s invasive that can really track people’s locations over a huge amount of time, I think it should be reserved for investigations into serious crimes.”

Will the 2020 Election Hinge on Empathy?

It was Tuesday, June 9, and Joe Biden was speaking—virtually—at the funeral of George Floyd, the black man whose death under the knee of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin tore the Band-Aid off the racial wound in America that those less affected by it had been all too willing to ignore. “To George’s family and friends, Jill and I know the deep hole in your hearts when you bury a piece of your soul deep in this Earth,” Biden said in a video that played over the faint tickling of piano keys in Houston’s Fountain of Praise church. “We know you will never feel the same again. … Unlike most, you must grieve in public. It’s a burden. A burden that is now your purpose to change the world for the better, in the name of George Floyd.”

That same morning, Donald Trump’s attention was focused on the widespread protests and unrest that had beset the country in the wake of Floyd’s killing. “Buffalo protester shoved by Police could be an ANTIFA provocateur,” he tweeted, referencing a viral video in which a 75-year-old man was pushed to the sidewalk by police and could be seen bleeding from his ear. “He fell harder than was pushed. Was aiming scanner. Could be a set up?”

In a piece for the site, Declan explores the 2020 election through the lens of what political scientists might refer to as the “empathy gap.”

In a campaign that is, as of now, likely to be defined by a pandemic, mass unemployment, and a citizenry increasingly coming to terms with racial injustices, Trump has an empathy problem—and it’s only getting worse.

This isn’t a new conundrum for Trump: Even some of his staunchest supporters wouldn’t describe the president as compassionate—the brashness is part of the appeal. But 2020 is not 2016, and Joe Biden is not Hillary Clinton. Trump was able to squeak out a victory in the Electoral College four years ago with only 44 percent likely voters thinking he “cares about average Americans,” in large part because only 53 percent thought his Democratic opponent did. In an August 2016 NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll, one in five respondents reported believing neither major-party candidate cared about people like them.

That is decidedly not the case this year. What was a 9-point empathy gap between Trump and Clinton in 2016 has grown to 19 points with Joe Biden on the ticket. Sixty-one percent of registered voters in a May poll from Quinnipiac University think Biden cares about average Americans—an eight-point increase over Clinton overall, but a 15-point increase with independents (and a 6-point increase among Republicans). The former vice president’s numbers on the question improved by two points since March—over which time he forcefully denied a sexual assault allegation made by former Senate staffer Tara Reade.

“I think the Trump campaign has to be perpetually professionally paranoid simply because of the narrowness of his majority in 2016 and the lack of apparent ability to expand that coalition going into 2020,” said Michael Steel, a veteran of several Republican presidential campaigns. “They have to be cognizant of the fact that Secretary Clinton brought huge negatives—built by decades of unpopularity—into the 2016 race. So running against former Vice President Biden—who doesn’t have nearly that kind of baggage—is an inherently more difficult challenge.”

Worth Your Time

Theodore Johnson, a black Navy veteran, has a beautiful—and at times, heart-wrenching—piece for National Review discussing the protests of the past few weeks. “Slavery is often referred to as America’s original sin not because of white people’s treatment of black people but because a nation founded on the high-minded ideals of liberty and equality allowed the enslavement of human beings to persist,” Johnson writes. There has long been a gap between our ideals and our capacity to live up to them. And although our enormous progress on this matter is “a testament to exceptionalism,” Johnson writes, “the pats on the back end there; the thing is not resolved.”

President Trump will hold his first rally since suspending campaign events because of the pandemic next Friday in Tulsa, Oklahoma. In our current political moment, the date, June 19, has sparked controversy in some quarters due to the historical significance of Juneteenth, which commemorates the end of slavery in the United States. The Trump campaign’s choice of city has added fuel to the outrage. Nearly 100 years ago, Tulsa was the site of what may have been the single most violent racial massacre in United States history. This collection in the Tulsa World does a really nice job explaining the history.

In his Wednesday column, Reason’s Nick Gillespie dives into the controversy that the classic American film Gone With the Wind has found itself in in recent days. HBO Max just removed the movie because of its romanticization of slavery, but instead of avoiding our country’s pernicious infatuation with the Antebellum South, Gillespie urges us to confront it head on, and to ask difficult questions about why it is part of our national culture. Anything less would be counterproductive. “There are lessons to be drawn from critically engaging our cultural past, especially at moments of tension and conflict,” he writes. “The urge, however well-intentioned and temporary, to shoo it away rarely leads to resolution and instead forestalls the sort of reckoning that is already long overdue.”

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

In yesterday’s French Press (🔒), David discusses the civil war that unfolded last week within the ranks of the New York Times over a Tom Cotton op-ed. Hearkening back to last summer’s French-Ahmari wars, David discusses how this event reminds us that assault against liberalism “now spreads across America’s political tribes” and is far from over.

American Enterprise Institute scholar and China expert Oriana Skylar Mastro joined The Remnant to talk with Jonah about China’s ambitions on the world stage. Check out this episode to learn about China’s relationship with Russia and to hear what’s happening on the Sino-Indian border.

In yesterday’s Advisory Opinions episode, Sarah describes her preferred mode of self-care by likening this podcast to getting a manicure. Still not sold? David and Sarah also discuss polls on the Black Lives Matter protests, the legalities of Confederate statues and calls to remove them, and the most recent Michael Flynn brief. Bonus: Gone With the Wind.

On the site today, Tyler Groenendal notes the problems with the fact that Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer cited “science” even while enacting arbitrary and confusing lockdown measures in her state, but then went out herself and marched with protesters.

Let Us Know

One of your Morning Dispatchers is decamping on a cross-country road trip tomorrow, and, as such, is spending the rest of the day today compiling the perfect road trip playlist. Send in your music recs!

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Nate Hochman (@njhochman), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.