As I travel around the country, I’m often asked whether 2016 and the rise of Donald Trump changed me in any way. In some quarters of the pro-Trump right, there’s often a narrative that Trump broke his critics’ brains. They’ve got Trump Derangement Syndrome. In some quarters of the left, there’s a belief that people like me are accountable for Trump’s rise. We may have opposed him in the election, but we helped create the cultural and political conditions in which Trump thrives.

I used to have a quick answer to these inquiries. I haven’t changed. Not at all. I didn’t leave the Trump GOP; the Trump GOP left me. Oh, and don’t blame me for Donald Trump. I was never one of those fire-breathing own-the-libs, polemicists.

But now I know that’s not right. I have changed. I’ve changed quite a bit. And a recent online spat over a picture of Mike Pence praying illustrated exactly how my mind and heart have changed in four short years. I’m reminded of the climactic scene in Pixar’s Ratatouille where the food critic Anton Ego demands to be served a dose of “perspective.” Well, I’ve been served heaping helpings of perspective, and it’s changed the way I view our nation, our culture, and our politics.

Let’s start with a tweet that briefly lit up right-wing Twitter last week. Here it is, from a New York Times Magazine and Harper’s writer named Thomas Chatterton Williams:

Before Trump, this was easy content. I have a column idea! Write a piece that critiques the tweet and explains to my secular friends that, no, Mike Pence isn’t trying to pray the virus away. Instead, he’s doing what people of faith have done for millennia as they face a daunting task—pray for wisdom and courage, acknowledging that God’s grace is indispensable to their success.

And lest we quickly condemn Pence for an “exhibitionist” prayer for purely political purposes, let’s not forget that there are tens of millions of Americans who are deeply reassured that they have a vice president who prays. I have my critiques of Franklin Graham’s political voice, but this tweet aptly captures the thoughts of many, many American Christians:

Moreover, presidential (or vice presidential) prayer isn’t partisan. Google “Barack Obama praying” and watch the images of Obama at prayer populate the screen. Here’s my favorite:

Indeed, as a number of people pointed out on Twitter, the president of the United States led the American people in prayer on one of the most fateful days in American (and world) history—June 6, 1944. If you haven’t heard Franklin D. Roosevelt’s D-Day prayer, I’d encourage you to listen. It captures the terrible gravity and danger of the moment. It never fails to move me—especially as I think of the millions of mothers and fathers consumed with fear for the fate of their sons. These words are so very powerful:

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men's souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

For these men are lately drawn from the ways of peace. They fight not for the lust of conquest. They fight to end conquest. They fight to liberate. They fight to let justice arise, and tolerance and good will among all Thy people. They yearn but for the end of battle, for their return to the haven of home.

Some will never return. Embrace these, Father, and receive them, Thy heroic servants, into Thy kingdom.

Yes, our leaders pray. They have prayed. And I hope they will continue to pray so long as this nation lasts.

So that’s 2016 me. I believe those words are true, but they’re incomplete. They lack perspective. The job of a politician, pundit, or activist isn’t just to determine what’s true, but also what’s important. It’s also to provide context. And this is perhaps the job that we fail most of all—in part because there are incentives to fail. There are incentives to sensationalize and generalize.

Think of the countless articles and public controversies based on nothing more than random tweets—each article centered around the idea that each tweet is further confirmation of what they think about us. We pick and choose from the public statements of our opponents, and engage only with those that confirm our biases.

You see it all the time. A single person and single tweet symbolizes “the left” or “the media.” And so it was with Williams. Here, for example, is Mark Meadows, the newly named White House chief of staff:

Here’s the former attorney general of the United States weighing in:

Yes, we know that there are people in the United States who mock the power of prayer. We know there are cultural conflicts. We see it all around us. But is Thomas Chatterton Williams’s tweet evidence about what “the left” believes about Christians, or is it evidence of what he thinks about Mike Pence?

And is a tweet by a man with 20,000 Twitter followers worth articles and tweets and condemnations from individuals and media outlets with large followings and serious influence? Moreover, does anyone bother to learn anything about Williams himself, or should we use our platforms to make him famous for one tweeted take?

It turns out that Williams is an interesting thinker who has written bold and brave things about race. He’s the son of white mother and black father. He’s married to a white French woman named Valentine, and they have a fair-skinned, blonde, and blue-eyed daughter. He’s written about the complexities of his family and his identity in a book called Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race.

My friend Kyle Smith wrote in National Review (yes, conservative National Review) that Williams’s book is “beautifully written” and it directly attacks the notion that race should be central to identity. Here’s the key part of Kyle’s review:

The notion of distinct human races is relatively new, Williams says, dating back to Enlightenment Europe, and the idea that having “one drop” of sub-Saharan African blood makes you a black person is directly traceable to Southern slaveholders and to Nazi purity tests. A Nazi view of race “essentialism” persists today, only we dress up the notion with euphemisms such as “culture,” “ancestry,” or “ethnicity,” as if your skin color binds, limits, or defines you. Why sign up for this? Williams notes that he is aware that “most so-called ‘black’ people do not feel themselves at liberty to simply turn off or ignore their allotted racial designations. . . . But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t.” White people should cast off “whiteness” in much the same way. Whether you identify as white out of “vicious bigotry or well-meaning anti-racism is of secondary concern,” Williams writes. “Essentialism . . . is always an evasion of life; the beautiful truth, in all its complexity, is that we all contain multitudes. Purity is always a lie.”

In other words, Williams is more than the sum of his tweets about Pence. He’s a thoughtful man with important things to say. And people I respect also respect Williams:

I have no idea how he’s responding to the online shame storm. Some folks can simply brush it off. Most who aren’t used to it can find it debilitating and sometimes frightening. Williams isn’t a presidential candidate, elected official, or a household name in American politics. He’s a thoughtful man with a modest following who was arguably Wrong Online, and now—apparently—to some folks he’s a symbol of an entire, hostile political and cultural movement.

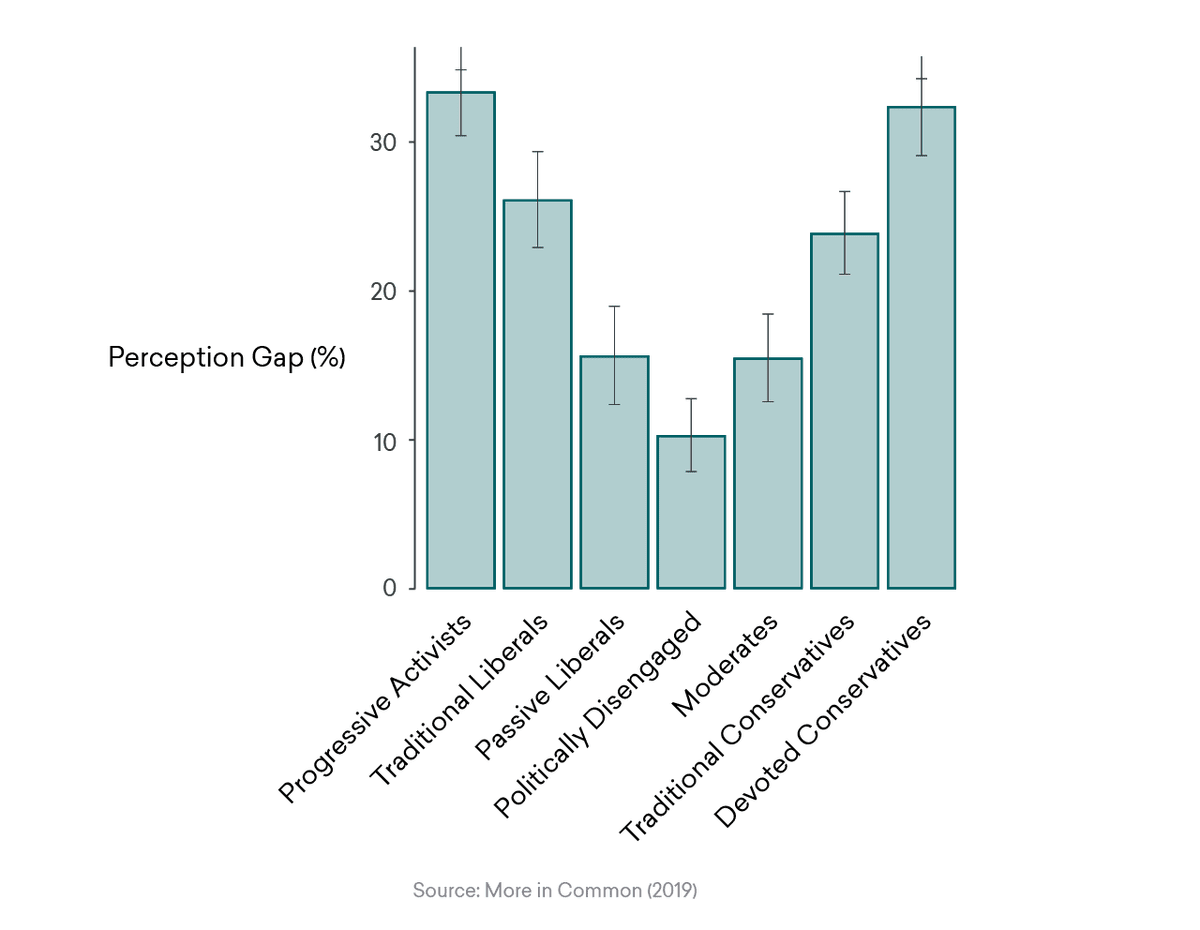

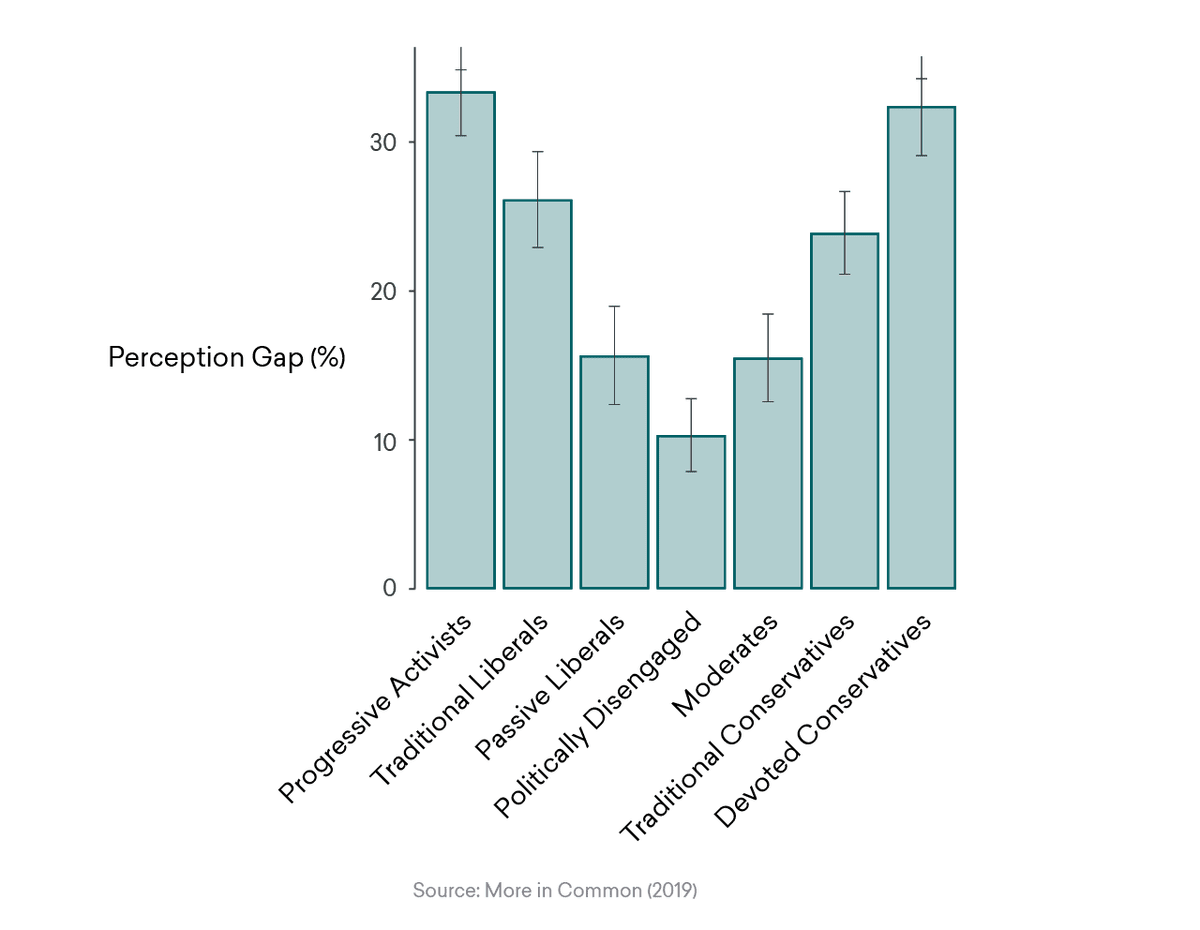

Last year the More in Common project released a study on the immense perception gap in the United States. It turns out that the Americans who are most engaged in politics have the most distorted perceptions about people on the other side. More exposure to political media made people more ignorant about the true beliefs of their political opponents. Progressive activists and devoted conservatives believe that their opponents are more extreme than they truly are:

Those who shun mainstream media to find the “true story” in partisan outlets are, unsurprisingly, often the most distorted in their views:

If you want to know how this happens—how the most engaged people can not only hate their opponents with white-hot hatred and also be fundamentally wrong about their beliefs and character—look no further than the tempest in a teacup about Mike Pence’s prayer.

That’s not to say that Williams is beyond critique because his other work is good, but those of us with a public voice have a public responsibility to decide not when someone is wrong but also whether their tweet or idea is worth using our public voice to address.

Is a person with 20,000 Twitter followers representative of a large cultural groundswell? (That might sound like a lot but the most influential media figures and politicians have followers numbering in the hundreds of thousands and sometimes millions.) If so, then where are the other, more powerful voices making the same statements? Why not take on those with followings so large that their influence is undeniable?

And if we choose to use our own voice to elevate and critique Williams, can we do the due diligence to place his thoughts in context and provide our readers with a more-complete picture of the man? Can’t we humanize him rather than merely toss him to the online wolves?

Our public discourse is trapped in an outrage cycle. We look for tweets and comments that appear to confirm our worst fears about our opponents, and when we find an outrageous comment, we retweet it, quote it, and repeat it as “proof” that our fears were true. Here is the person who “said the quiet part out loud” or turned “subtext into text.” He’s “the left.” She’s “the right,” and with each salvo in the endless war we retreat farther and farther from the perspective we truly need.

One last thing ...

You’ve emailed, and I’ve read your feedback. Some of you love the closing music videos, especially the more contemporary praise and worship songs. Other folks, not so much. “Where are the classics?” you ask. Well, how’s this—Andrea Bocelli singing “Amazing Grace.”

Ever since my deployment, that hymn resonates so deeply with me. We played it every time one of our brothers fell, and it reminds me of one of the most touching memories of my life. Shortly after I got back from Iraq, several of us gathered at a friend’s house to remember and pay tribute to my friend Mike Medders, a Third Armored Cavalry Regiment officer who died on September 24, 2008, in Diyala Province, Iraq.

It was a warm summer night in the town of Avon Lake, Ohio. We were drinking, swapping stories. The atmosphere was festive—just like Mike would have liked. Then, we heard bagpipes. A neighbor was standing on the sidewalk at the end of the driveway, playing “Amazing Grace.” Everyone stopped. Everyone fell silent. We lifted our glasses in tribute to Mike, and then—when the song was over—the neighbor walked back into the darkness without saying a word.

And so, here’s a bonus, bagpipes version of the song—one of thebest I’ve heard. Come for the rousing rendition of “Scotland the Brave.” Stay for “Amazing Grace.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.