McPHERSON SQUARE—A few blocks north of the Smithsonian sits a lesser-known but worthwhile detour for District of Columbia residents and visitors alike: the Victims of Communism Museum. The collections, which opened to the public in June, honor the millions of people who have died at the hands of Communist regimes.

Last week, one of the ideology’s most vocal opponents took the time to walk me through a temporary exhibit on the Tiananmen Square protests and the massacre that brought them to an end.

In the years since Zhou Fengsuo first took to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square as a student organizer, he has dedicated his life to preserving the memory of an event that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would rather see wiped from the historical record. Over the course of more than six weeks in 1989, people in cities across China made a forceful call for democratic and economic reform through mass demonstrations. At the protests’ peak, an estimated 1 million people occupied the square.

“It was just spontaneous, like an eruption of a volcano. People’s true will was repressed so deep, for so long, that all of a sudden it had to come to the surface. We were all surprised,” Zhou said. “All of a sudden, we all realized that our opinion was not isolated, was not the minority. It was the true hope for change.”

But the movement is perhaps best remembered by its sinister end. In the sit-in's final days, CCP leadership ordered the army to turn its guns on the civilians it had once been charged to protect, killing thousands. The Chinese government continues to deny, conceal, and obfuscate the crimes of its former leadership to this day, threatening Tiananmen participants who remained in China against speaking out and systematically wiping evidence of the massacre from cyberspace.

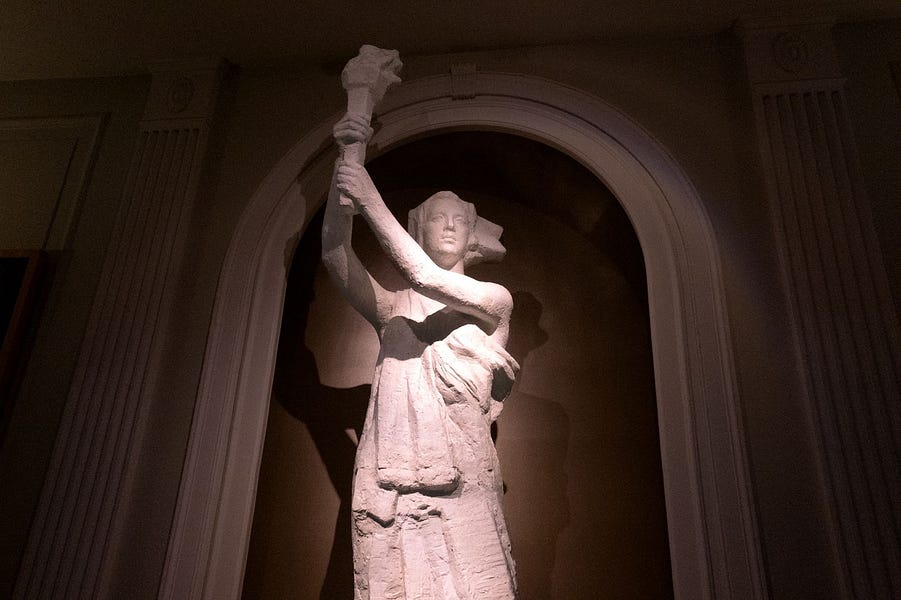

For the next five months, however, the Victims of Communism museum will host some of the physical relics of the dark yet hopeful period of Chinese history. Zhou hopes the collection will serve as a reminder of the enduring hardships faced by people living under CCP autocratic rule, as well as the lengths people will go to in pursuit of a free China.

A framed blood-soaked shirt greets visitors at the exhibit’s entrance. The garment belonged to a reporter employed by the Chinese military’s PLA Daily newspaper who, when troops entered the square, stood in solidarity with protesters. Another display features a leaflet on press freedom drafted by Zhou and his fellow students, and which a young woman who went on to become a journalist returned to him years later.

According to Zhou—who has taken up the near-impossible task of documenting Tiananmen’s victims—protesters with cameras were targeted more than any other single group: a real-time effort by the regime to bury its atrocities. Now, the CCP is carrying out a campaign of digital totalitarianism to transform Chinese civil society’s collective memory of its own past, removing any remaining pictures of and stories about the protests from the online public record.

It’s been effective. Asked if there’s a strong appetite to learn about the 1989 demonstrations and military crackdown in mainland China, Zhou said no, in part because of people’s reluctance to grapple with their own leadership’s tainted history. “If you know that this government has committed such heinous crimes against its own people, what would you do?,” he asked.

Hong Kong is a different story. In the immediate aftermath of the military crackdown, the then-British colony played a crucial role in relocating persecuted protesters overseas and away from CCP jurisdiction. In the years after 1989, the city has paid tribute to the massacre’s victims through annual vigils and events. It’s also home to one of the world’s only permanent exhibits on Tiananmen, the June 4th Museum.

But as the CCP has taken steps to dismantle the territory’s semi-autonomous status in recent years, it has also cracked down on local organizations and individuals responsible for keeping the memory of Tiananmen alive. Several members of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China—which runs the now-shuttered June 4th museum—are currently imprisoned. Last month, police arrested at least six people for holding a candlelight vigil on the 33rd anniversary of the military crackdown.

“This is an important part of their identity. Many of the protesters in Hong Kong grew up going to the Tiananmen memorials. This was their political awakening,” Zhou said. “We were all hoping that Hong Kong’s freedom could propagate to China, but now the totalitarian regime keeps expanding.”

“That’s one motivation of why we are doing this here, because we have the freedom and the capacity to do it,” he added.

The collection also features the official blue and white flag of Shenzhen University, flown by student protesters in the square. On it are the signatures of 92 people, including police officers, doctors, and journalists. “Long live press freedom!,” one inscription reads. “Beijing police solute the students at Tiananmen Square,” reads another.

“Today, a lot of people buy into this idea that Chinese people are different, that they need a different way of governing. That’s completely wrong,” Zhou said. “The majority of people in Beijing and people from all over China—over 400 cities—and not only students—people from all walks of society—all had this common dream of a free China. It was almost within reach.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.