The meanings of terms change over time.

Analyst Ron Brownstein takes credit for coining the term “blue wall” in 2009 to refer to “the 18 states that … backed the Democratic nominee in at least the [1992 to 2012] presidential elections; together with the District of Columbia, they offer 242 Electoral College votes.”

Which was true until it wasn’t, which happened when Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania fell out in 2016 and went narrowly to Republican Donald Trump. They got back in line in 2020, but, having revealed themselves as vulnerable to the GOP, haven’t fit so snugly into the mortar as before.

Part of this is about the psychology of campaigns and voters. Michigan, for example, isn’t that much less Democratic than states like Minnesota and Virginia, but being identified as a “swing state” means that campaign resources come flooding in and that voters themselves feel special motivation to stay engaged, volunteer, urge friends and family members to vote, etc.

If Republicans poured as much time and money into Virginia as they are into Pennsylvania, you can bet the race would be closer there. But campaigns have finite resources—particularly the time candidates have to spend—and have to allocate them to the states they have the best chance of winning, or, more often, vulnerable spots where they can least afford to lose.

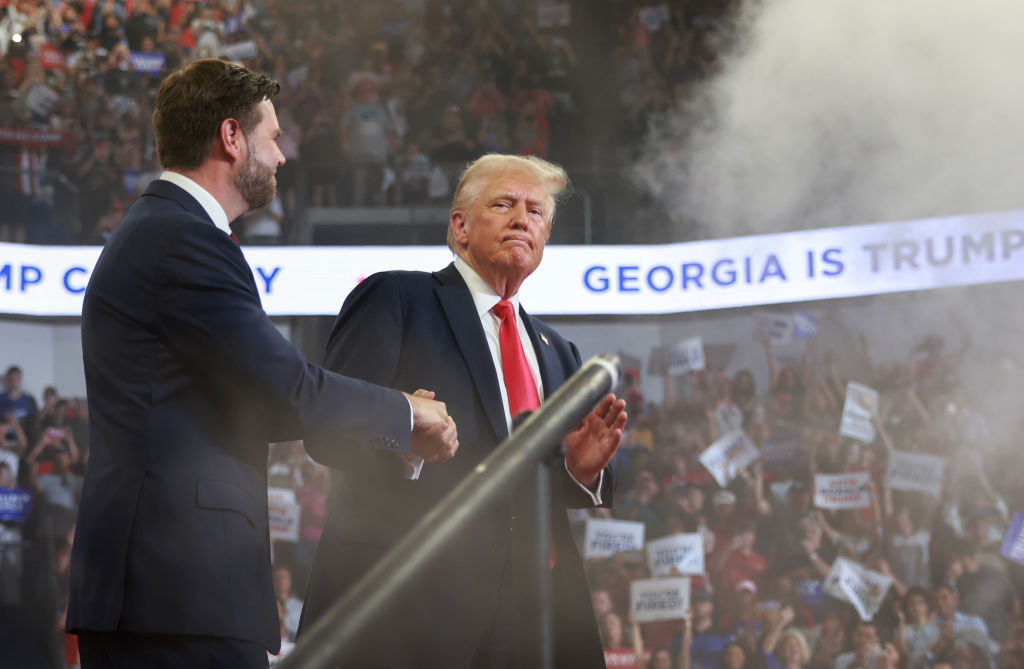

“Blue wall” today doesn’t refer to Brownstein’s 242-electoral vote empire of the Clinton and Obama eras, but just the three renegade states of 2016 and their 44 electoral votes of the Trump era. If Trump cracks through the wall in any of them, he will likely win the presidency.

As we’ve discussed before, if Trump is running well enough to win any of the three blue wall states, he almost certainly will have won every other more Republican-leaning state. He can get to 262 electoral votes without any piece of the blue wall, and then each piece of it would have enough electoral votes on its own to put him over the top.

Brownstein says he coined the term to refer to Democrats’ strengths in the Electoral College, but it has come, as words often do, to mean the opposite: Democrats’ weak spot.

But if there’s a blue wall, then there is a red wall, too. Not the states Trump won narrowly in 2016, but those he lost, or almost lost, in 2020.

Arizona, North Carolina, and Georgia add up to 43 electoral votes, and all were rock-ribbed Republican states for most of the past 40 years—or longer.

Until 2020, Republicans had carried Arizona in every presidential election since Dwight Eisenhower’s first term except for 1996, when a big protest vote for Ross Perot narrowly tipped the state to Bill Clinton in his reelection campaign. Barry Goldwater’s state wasn’t always a GOP blowout win, but it was certainly not up for grabs. And then, whoops, it slipped through Republicans’ fingers by just 10,457 votes in 2020.

For Republicans it was as painful as when Democrats had watched true-blue Michigan fall away by 10,704 votes in 2016. Democrats did not take that well. Republicans, though, became completely unhinged. Welcome to the red wall, Arizona.

North Carolina stayed Republican through both Clinton elections, sticking with the GOP from 1980 to 2008, when it took the nation by surprise and went for Barack Obama. It reverted to form the next cycle, but, like its blue wall counterparts to the north, North Carolina had put the smell of blood in the water and would become a target for ambitious Democrats going forward. When it ended up as the state with the narrowest margin of victory for Trump in 2020, North Carolina was fully inducted into swing state status and became a part of the red wall.

Georgia, though, was the biggest surprise. While the Peach State had been sluggish in its switch to the red team in the second half of the 20th century compared to its fellow former Confederate states—no doubt in part because Democrats nominated its former governor, Jimmy Carter, for president—when it came in for the GOP, it did so with vigor.

George W. Bush won Georgia by 12 points in 2000 and 17 points in 2004. Even in the worst Republican year this century, 2008, the state was never in play and John McCain breezed in with a 5-point win; about the same as Trump would turn in eight years ago.

But in 2020, Georgia fell out with the GOP over Trump. By an agonizing 11,779 votes, Republicans watched their onetime bastion turn blue. When Georgia elected two Democrats to the Senate in 2021, and reelected one in 2022 despite a commanding win for the state’s conservative Republican governor, it had unlocked red wall status for sure.

While alike in so many ways, the key difference between the two walls is that Vice President Kamala Harris can win the presidency without winning any of the red wall states. If she keeps the blue wall, she could even let little Nevada and its six electoral votes slip away, and still get to 270 electoral votes. (Now you see why the Trump campaign was in such a tizzy about trying to change the electoral math in Nebraska and deny Harris one vote there.)

But they are alike in this essential way: Neither campaign can afford any breaches in its respective wall.

The New York Times has in recent days helpfully provided us with polls of all three red wall states. For the blue wall, the Times chipped in with Pennsylvania, but we turn to the sturdy survey work of Marist College for Michigan and Wisconsin.

And guess what? Harris is leading in all the blue wall states, with the narrowest advantage in Wisconsin, and Trump is leading in all the red wall states, with the narrowest advantage in North Carolina.

So if you live in Milwaukee or Charlotte, hang in there, because the next six weeks are going to be hell on wheels.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.