Last weekend, a memorial service was held for Michael Gerson at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. I never met him, but I often felt I was meeting a kindred soul in his many columns, in the book he co-authored about religion and politics, and in the speeches he wrote for President George W. Bush. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was partly his voice I heard in one of the most remarkable speeches I’ve ever heard.

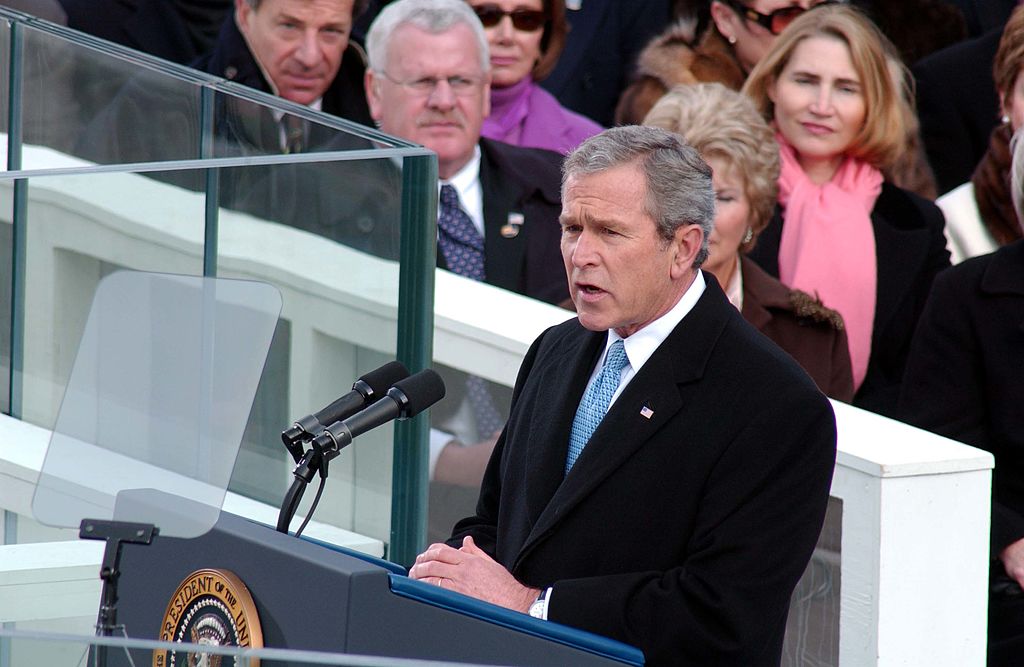

It was 35 degrees on the National Mall on January 20, 2005, one of the colder inaugurations on record. I arrived around 9 a.m. and spent hours elbowing my way, block by block, through several hundred thousand people gathered to watch Bush take the oath of office a second time.

Protesters were out in droves: black-clad anti-globalization protesters in ski masks; anti-war protesters dressed in orange prison jumpsuits reenacting the abuse scandals at Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib; and general left-wing anti-Bush protesters. I found my corral way back on the Mall, somewhere behind the reflecting pool, and stood shivering for an hour or more waiting for the ceremony to begin. The inaugural stand was a distant stage.

“I want this to be a freedom speech,” Bush had told Gerson, then his chief speechwriter. Gerson later reflected in his memoir, “He was looking for a summary of everything that had come before, and a fully formed vision of the Bush foreign policy.” Bush and Gerson succeeded. With unmistakable clarity, Bush called out and condemned the evils and dangers of tyranny—elevating the light of freedom by contrast with its opposite.

“For as long as whole regions of the world simmer in resentment and tyranny—prone to ideologies that feed hatred and excuse murder—violence will gather, and multiply in destructive power, and cross the most defended borders, and raise a mortal threat,” Bush said at the beginning of the speech, “There is only one force of history that can break the reign of hatred and resentment, and expose the pretensions of tyrants, and reward the hopes of the decent and tolerant, and that is the force of human freedom.”

Then and now, I like this kind of thing. Moral clarity on ultimate things is important, even if the details of public policy inevitably dwell in shades of gray. Some presidents spend all their time in wonky details (Bill Clinton) or vacillate about America’s role in the world (Barack Obama) or fail to project confidence (Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush). I appreciated the younger Bush’s mix of clarity and confidence. Still, almost every president preaches the sermon of liberty. Bush’s speech, to this point, was rhetorical boilerplate: expected, enjoyable, but unremarkable.

Bush was working up to something more. “We are led, by events and common sense, to one conclusion: The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands.” Tepid applause from the audience, but I perked up. Bush was moving toward something I had wanted to believe since 9/11. “The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.” More applause. “America's vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one.”

This was more than boilerplate. This was a proclamation that the answer to American security was American idealism. Scholars of American foreign policy describe the tension between realists and idealists that has always animated debates about our role in the world. Bush was claiming that, in the long run, the two do not conflict; they harmonize.

If true, the harmony of freedom with security has enormous implications for America’s role in the world. Gerson and Bush did not shrink from describing them. “For months, I had searched for a strong, single-sentence description of the goals of the Bush Doctrine,” Gerson wrote in his memoir. He consulted with historians and political scientists. The eminent Yale historian John Lewis Gaddis had a specific suggestion, a bold goal that captured the essence of Bush’s “freedom speech.” Gerson loved Gaddis’ idea. “I brought the idea to the president, who embraced it.” It became the centerpiece of the speech, the line the world would remember:

“It is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture,” Bush said, “with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

I remember being startled the moment I heard the words. My ears flinched. I wasn’t sure if I had heard what I thought I had heard. I looked around at the bundled-up men and women shivering on the Mall with me to see if they had heard the same thing I had. They were politely clapping their mittened hands. I thought I caught an undercurrent of murmuring, as if they didn’t know what to make of it.

Some critics called it “messianic” and “extraordinarily ambitious,” and accused Bush of announcing a “crusade.” The conservative columnist and former Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan said the speech “left me with a bad feeling, and reluctant dislike,” because it had “no moral modesty,” no “nuance.” The goal of ending tyranny was “somewhere between dreamy and disturbing,” a case of “mission inebriation.” “This world is not heaven,” she chided.

But, as Gerson later noted, “in the speech, this goal is immediately and carefully qualified.” Bush noted that ending tyranny “is not primarily the task of arms,” that “freedom, by its nature, must be chosen,” and that “when the soul of a nation finally speaks, the institutions that arise may reflect customs and traditions very different from our own.” It was “the concentrated work of generations,” and “America will not impose our own style of government on the unwilling.” Noonan was wrong: Bush was remarkably and explicitly humble and realistic in describing the goal of ending tyranny, which elevated his vision further.

This was no utopian or imperial mission to conquer the world in the name of saving it. It was a statement of principle, sketching an orienting framework within which to understand who we are and what we stand for. Bush was pointing to a polestar, a single fixed point to help guide the ship of state through the storms and winds that would always come.

Bush’s statement was ambitious, yes, but consider the opposite view. Freedom is the prerogative of a few, the unique heritage of American experience and our European forebears. We cherish the flame, but have no interest in its spread. We respect that other peoples are neither fit nor ready for its blessings and often prefer their ways to ours.

Gerson had heard the argument before. “Some are convinced that American liberty, based on ancient British institutions and Christian cultural habits, is unique and unexportable,” he wrote, “Some assert the absolute priority of cultural norms over philosophical abstractions like the Declaration of Independence.” But:

If the Declaration of Independence is not a myth and a lie and a fraud, it is true for everyone. That truth is never convenient. It often upsets a false stability. Affirming that truth may provoke the bitterness of violent men. The triumph of that truth may be preceded by decades of defeat and disappointment, when cynicism seems to all the world like realism. But the truth of human dignity and equality always and eventually emerges, with a sudden splendor. Always. Followed to its logical conclusion, the inalienable right of all men to be free implies and requires the end of tyranny in our world.

The objection to Bush’s universalism cloaks itself in the language of humility but it is, at heart, cultural condescension. “America will not pretend that jailed dissidents prefer their chains, or that women welcome humiliation and servitude, or that any human being aspires to live at the mercy of bullies,” Bush said in the speech. The only critics who argue that their people are not ready for democracy are rich men of the ruling tribe. They defend autocracy because they are its beneficiaries, not its victims. The victims know better.

The legacy of Bush’s second inaugural has inevitably been shadowed by the outcome of the wars fought under its banner. Some, including President Donald Trump and the portion of the Republican Party he represents, believe the lesson of the failed wars is that Bush was wrong, root and branch, about the whole thing, including the ambition to end tyranny. In their view, the United States needs to temper its ambitions, do less in the world, and abandon its democratic mission. They echo Noonan’s critique: Bush’s speech was too much.

The problem with the speech’s legacy is not the presence of moral ambition, which is necessary, but that we failed to take note of the rest of the speech, after the declared goal of ending tyranny. We forget the humility and realism, and we forget that Bush went on to speak of the importance of character, integrity, and family; of community, religion, and service to others with “mercy, and a heart for the weak.” He called on Americans to embrace love for their neighbors and to “abandon all the habits of racism.” Ambition without character does indeed lead to arrogance, moral compromise, and failure, Bush seemed to be saying, even as he warned that character without ambition is too passive in the face of evil.

Some dismissed Bush’s rhetoric as “neoconservatism.” The use of such a label serves to reject Franklin Roosevelt, who spoke of the Four Freedoms and of “democracy’s fight against world conquest” in World War II; the Truman Doctrine, a foundation of our successful Cold War strategy; and John F. Kennedy’s call to “pay any price, bear any burden” to “assure the survival and success of liberty.” And it is a rejection of Ronald Reagan, who in 1983 said, “Freedom is not the sole prerogative of a lucky few, but the inalienable and universal right of all human beings.” Bush was squarely within the mainstream of views about America’s role in the world.

The strongest vindication of Bush’s vision came a few years later from the president who succeeded him. While opposing Bush’s war in Iraq, Barack Obama nonetheless affirmed his “unyielding belief that all people yearn for certain things: the ability to speak your mind and have a say in how you are governed … [and] the freedom to live as you choose.” Obama was addressing an international audience in Cairo, Egypt, which made more dramatic his insistence that, “These are not just American ideas; they are human rights. And that is why we will support them everywhere.”

Obama’s striking echo of Bush’s language suggests that Gerson was right. The ideals of freedom and equality are the polestar for America’s role in the world, even when we fail in our ambition to reach them. If Bush’s speech had been nothing more than a triumphalist recitation of soaring ideals, it would be cheap, detached from reality, and just as easily ridiculed as forgotten. But the overlooked realism and humility that pervade the speech allow it to live past its moment—and elevate it as one of the greatest American speeches in living memory.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.