California may have voted for Joe Biden by about 30 points, but other election results were a decidedly mixed bag for the famously blue state. Four ballot measures—which California uses more often and for bigger issues than any other state—that would have enacted long-desired progressive priorities have failed or appear likely to lose.

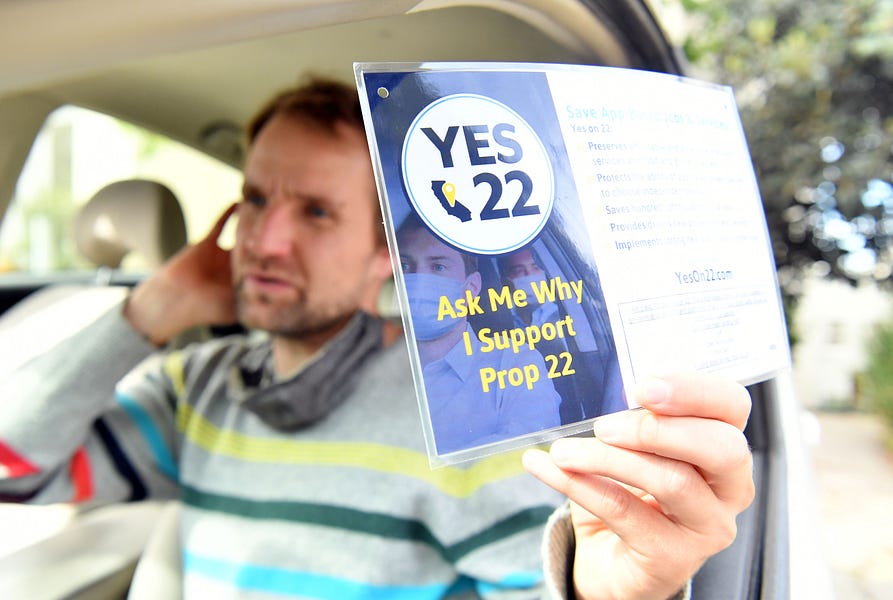

Proposition 22, the measure that has attracted the most national attention, is also California’s most expensive ever, with more than $200 million of total spending. Officially titled the “App-Based Drivers as Contractors and Labor Policies Initiative,” it was a direct response by rideshare-based companies to Assembly Bill 5, passed to force companies to hire workers as employees rather than as contractors or freelancers. After it went through several rounds of carve-outs and exceptions, it ended up mainly as a dagger aimed at companies like Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash. Reclassifying drivers as employees with benefits rather than contractors would have massively increased labor costs—so much so that the two companies threatened to end operations in California before a court granted a stay in August.

So Proposition 22 emerged as the tech industry’s response. It classifies “app-based drivers” as contractors while entitling them to limited benefits, and it makes the rule modifiable only by a 7/8th vote of the legislature. It is currently winning easily, 59 percent to 41 percent, with 84 percent of the votes counted. The yes campaign raised $180 million, mostly from the three companies mentioned above.

But Kenneth P. Miller, a professor at Claremont McKenna College who studies California politics and history, told The Dispatch that he was skeptical about the influence of all that spending. “People like Uber and Lyft, and this was going to the carotid artery of the whole gig economy.” Miller noted that the “yes” side’s messaging focused less on the threat to Lyft and Uber and more on the appeal of flexible “new economy” jobs to many workers.

The result was a major defeat for labor groups and national politicians like Elizabeth Warren who favor much tougher regulation of the tech industry.

While Proposition 22 sucked up most of the California media oxygen this election cycle, other major progressive goals were defeated as well. Proposition 16, put forward by Democrats in the state legislature, would have repealed California’s longstanding ban on affirmative action. Like Proposition 22, it has been defeated by a solid majority of voters, with polling finding tepid support among all racial groups save African Americans. It’s slightly unclear why it failed, however.

David McCuan, a professor at Sonoma State who studies ballot measures, noted that on many issues, California is “purple” but doesn’t always fall into predictable partisan patterns. “A Valley Democrat eats a coastal Santa Cruz Republican for lunch” in terms of conservatism on social issues, he noted. Miller also attributed some of the distaste for Proposition 16 to the balking of committed progressives, who saw the legislation as negatively impacting their children’s chances of admission to the University of California.

Proposition 16’s supporters, however, point to voters being confused by the law’s language as the main reason for the loss. There may actually be some truth to this, and it illustrates an important dynamic in how Californians vote on ballot measures. As Mark Baldassare from the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonpartisan think tank, put it, for California voters, “the default is to vote no” on poorly understood propositions.

Maria Morgan, a San Mateo resident who says she is an independent who usually votes Democratic, told The Dispatch that she voted no because she had “no idea what it was.”

Morgan also said she “assumed affirmative action was already practiced in the state,” a common perception in California, where many government officials try to circumvent the ban on affirmative action in any way they can—for example pushing to do away with SAT and ACT scores for U.C. admissions because they are viewed as favoring white and Asian students.

That’s not the only longstanding populist conservative initiative under assault by Democrats this election. Proposition 13, led by activists Howard Jarvis and Paul Gann, passed in 1978 and established strict limits on how much property taxes can be increased on buildings built before 1976. This year’s Proposition 15 aimed to take a chunk out of Proposition 13 by removing its property tax protections from commercial buildings. Proposition 15 had a closer race than the other two mentioned, but ended up losing by around four percentage points.

The defeat of these three measures, Miller said, highlights how even in deep-blue California “there is a limit to voters’ progressivism.” And McCuan added that the losses, along with defeats for union-backed Proposition 23 (regulating dialysis clinics, including mandating an on-site physician) and for Proposition 21 (expanding rent control) would also probably serve as warnings to Democrats nationally. Many California ballot measures are “a finger in the wind,” for Democrats, McCuan said. Democratic politicians who hoped to push for versions of AB5 in other states, or to expand affirmative action programs, are most likely chastened by the results.

And for California progressives who view their state as a laboratory for progressive policy, the elections are a reminder that even though California has a deserved reputation for being on the bleeding edge of liberal politics, it still contains high numbers of registered independents and around 10 million Republicans. As Gov. Gavin Newsom likes to say, California is a “nation state”—and nations are rarely in lockstep agreement on anything.

Photograph by Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.