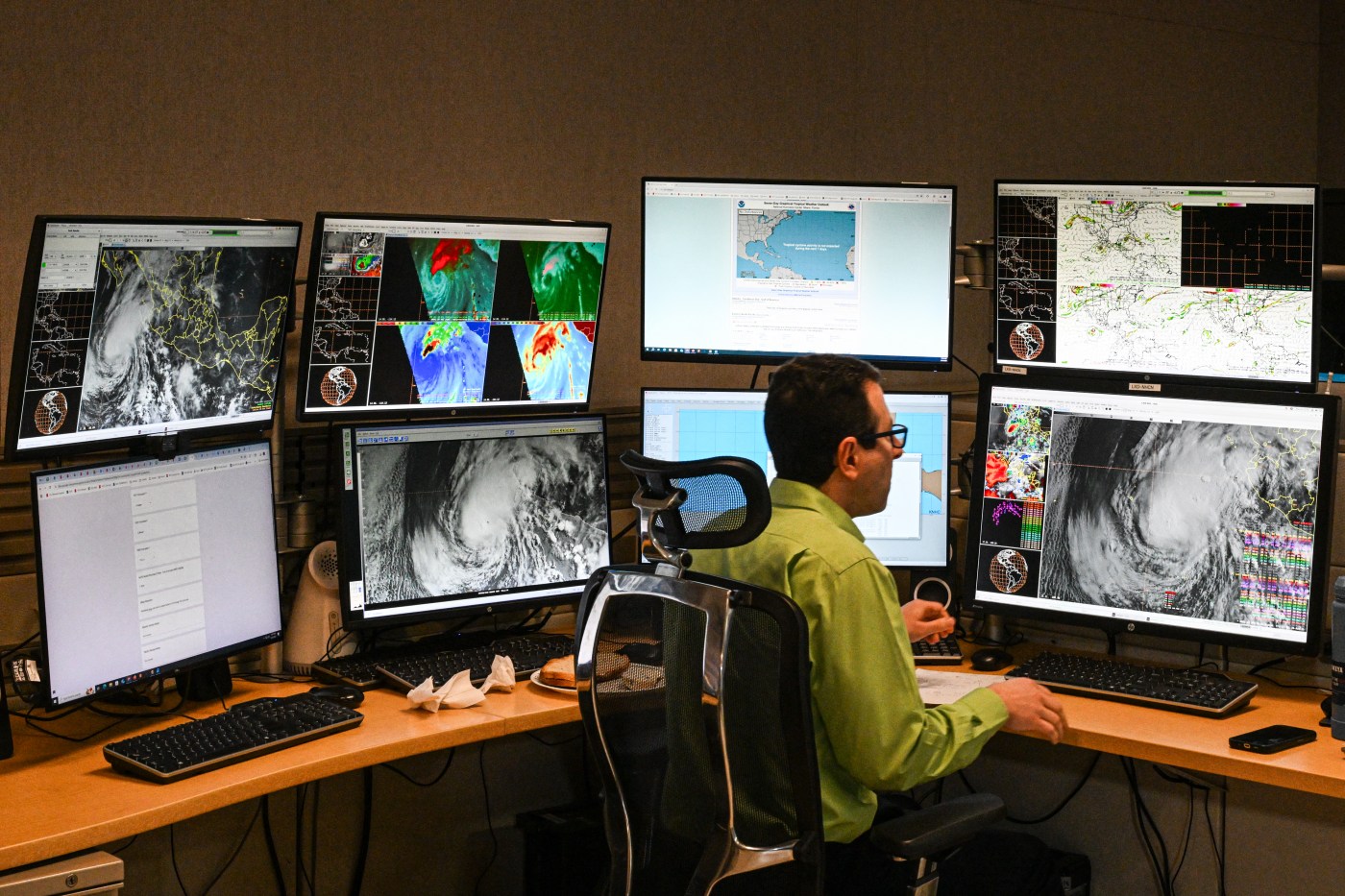

Hurricane season began this month, but a disaster has already befallen the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): big cuts in personnel and budget that, if media reports are correct, threaten the agency’s forecasting accuracy and put many U.S. residents at higher risk.

In late February and March, NOAA—the scientific and regulatory government agency whose diverse portfolio of line agencies and programs includes the National Weather Service (NWS), the National Hurricane Center (NHC), and the Storm Prediction Center—terminated well over 1,000 employees, or 10 percent of its total workforce, under orders from the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) initiative.

What got cut?

These terminations included two flight directors of NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter unit, which flies inside and next to hurricanes to collect critical data, reducing this staff to 60 percent of its ideal size and potentially grounding future flights.

In Florida, cuts at the NWS and workforce shortages of 40 percent at its Miami and Key West offices have made it harder for the service to keep staffed 24/7. More than 12 NWS offices along the Gulf Coast are currently understaffed. And launches of weather balloons, which gather upper-air weather data twice daily, have been suspended at locations across the U.S., potentially affecting NOAA’s Global Forecast System.

The NWS no longer covers the entire U.S. 24/7. Mike Smith, a noted meteorologist who has developed advanced severe weather warning technology and closely follows NOAA, told The Dispatch, “It’s terrible.”

Roger Pielke Jr., a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a sharp critic of NOAA’s now-terminated database on billion-dollar weather disasters, told CBS News, “I'm a huge fan of NOAA and the National Weather Service. They play a huge public service role, and I'm not happy with the sledgehammer that is being taken to the agency."

Publicly, NOAA insists it can fill mission-critical operational shifts this hurricane season. Privately, it is scrambling to fill vacancies, including at Gulf Coast offices in preparation for the June-through-November hurricane season, which the agency predicts will be “above normal.” Some positions “will soon be advertised under an exception to the Department-wide hiring freeze to further stabilize frontline operations,” NOAA public affairs specialist Erica Grow Cei said. Nebraska Republican Rep. Mike Flood has filed bipartisan legislation intended to protect NWS personnel, making it harder to fire them and classifying them as public safety employees to protect them from hiring freezes.

What’s at risk?

Much of the weather information you get from your phone app, TV, and radio originates from NOAA and its National Weather Service. And almost all data on hurricanes, blizzards, and tornadoes—95 percent or more, says Smith—comes from NOAA.

Weather data gathered by surface stations, weather balloons, and satellites forms the basis of NWS forecast models, and some experts fear the cuts may compromise the quality of those models. “The key for the forecast models is to keep all of the input data coming in,” said Phil Klotzbach, a researcher at Colorado State University.

The number of people and the amount of money at risk are enormous. More than 60 million U.S. citizens live in coastal areas directly affected by hurricanes, and millions more live in at-risk inland areas (think Asheville, North Carolina, after Hurricane Helene). According to the American Meteorological Society, “estimates of the value of weather and climate information to the U.S. economy exceed $100 billion annually, roughly 10 times the investment made by U.S. taxpayers through the federal agencies involved in weather-related science and services.” This compares with NOAA’s 2024 budget of $6.7 billion.

That payoff is accuracy. “Forecasts of tropical cyclone tracks today are up to 75% more accurate than they were in 1990,” said Chris Vagasky, a member of the American Meteorological Society and National Weather Association. Today’s three-day outlook from the NHC is as accurate as its one-day outlook was in 2002, he says, “giving people in the storm’s path more time to prepare and reducing the size of evacuations.”

Many believe the DOGE cuts will have immediate impact. As former NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad told The Guardian, “If I were a citizen of Texas, Florida or Georgia, I wouldn’t be sure how well warned I would be of a hurricane.”

The damage before DOGE.

Have the DOGE cuts to NOAA replaced MAGA with MAVA—Make American Vulnerable Again? According to Smith, NOAA was in far-from-perfect shape before Elon Musk fired up his chainsaw. Cancellations of weather balloon launches had begun during the Biden administration, setting “a dangerous precedent.”

Some of NOAA’s critical hardware has also seen better days. Its radar equipment is aging—some of it 30 years old and prone to frequent breakdowns. (Congress offered to fund “gap filler” radar equipment, says Smith, but was inexplicably turned down by the NWS.)

And not only is the radar old—in some areas of the country, the portions are so small. Parts of peninsular Florida are covered by just one radar, says Smith. An outage would make it harder for emergency managers, fire departments, search-and-rescue teams, and others who rely on this radar to do their jobs. Given NOAA’s long procurement cycle, Smith fears replacing radar equipment could take up to 15 years.

For years, Smith also has observed a slow brain drain at NOAA, mainly because of sclerotic hiring practices. Despite having hundreds of open positions, he says, NOAA can take as many as nine months to decide on a qualified candidate. Flood’s bill would give NWS direct hiring authority to speed up the process.

Some of NOAA’s problems may be cultural. The agency isn’t always scientific in making decisions, says Smith. For example, the meteorological community assumes that fewer weather balloon launches will degrade its forecasting. “The problem is, we haven't done those studies. We think more data corresponds to better forecasts, but we don't know.” It would cost relatively little to find out, he believes, compared to tens of millions of dollars spent on weather balloon launches.

Partly sunny, with a chance of debacle.

Still, Smith sees little direct effect from DOGE’s cuts on preparedness for the 2025 hurricane season. There may be fewer weather balloon launches, but he believes weather balloons matter least in hurricane forecasting. As long as Hurricane Hunters are flying and satellites are gathering data on the open ocean atmosphere, “We will probably be okay,” he says. But if cuts continue, as some are predicting, “then I would worry.”

How much should we worry? Smith points to NOAA’s diminished skill in tornado prediction. Over the last 15 years, the same hardware and personnel issues have caused “terrible decreases” in the accuracy of NOAA’s tornado warnings, he says.

Just before speaking to The Dispatch, Smith said he received a copy of the draft budget for the NWS the administration sent to Congress for fiscal year 2026, which begins on October 1.

While a recent report by The Hill warns of further big cuts to NOAA, Smith said the budget he was sent for the NWS includes a 5.3 percent increase over its actual budget for 2024, with a decrease in funding for its weather satellite program that he believes Congress will reverse, given its importance to forecasting. The NWS will be sufficiently funded, he believes, but recovering the expertise lost with DOGE-directed layoffs and early retirements “is going to be tough.”

What would he recommend? To buttress hurricane preparedness, Smith would immediately rehire the experienced employees who were terminated by DOGE and provide the funds and other resources needed to conduct NOAA’s hurricane reconnaissance flights.

As for NOAA’s attempts to re-staff its Gulf Coast offices, Smith is less optimistic. Given NOAA’s slow hiring pace, he is concerned that it can’t move quickly enough to make a difference for this year’s hurricane season.

Correction, June 11: This article has been updated to correct the first name of former NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.