Four years ago, Italy became the first and only G-7 member to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Now it wants out.

Joining the global infrastructure project was an “improvised and atrocious” decision, Italian Defense Minister Guido Crosetto said late last month. “The issue today is, how to walk back without damaging relations? Because it is true that while China is a competitor, it is also a partner.”

Italy’s planned withdrawal marks a major blow to the ambitious, multi-continent initiative, which seeks to connect Asia to Europe, Latin America, and Africa through the construction of ports, roads, railways, and pipelines. It also signals the European Union’s broader shift away from Beijing at a tense geopolitical moment, as the United States looks across the Atlantic for partners in countering China’s global influence.

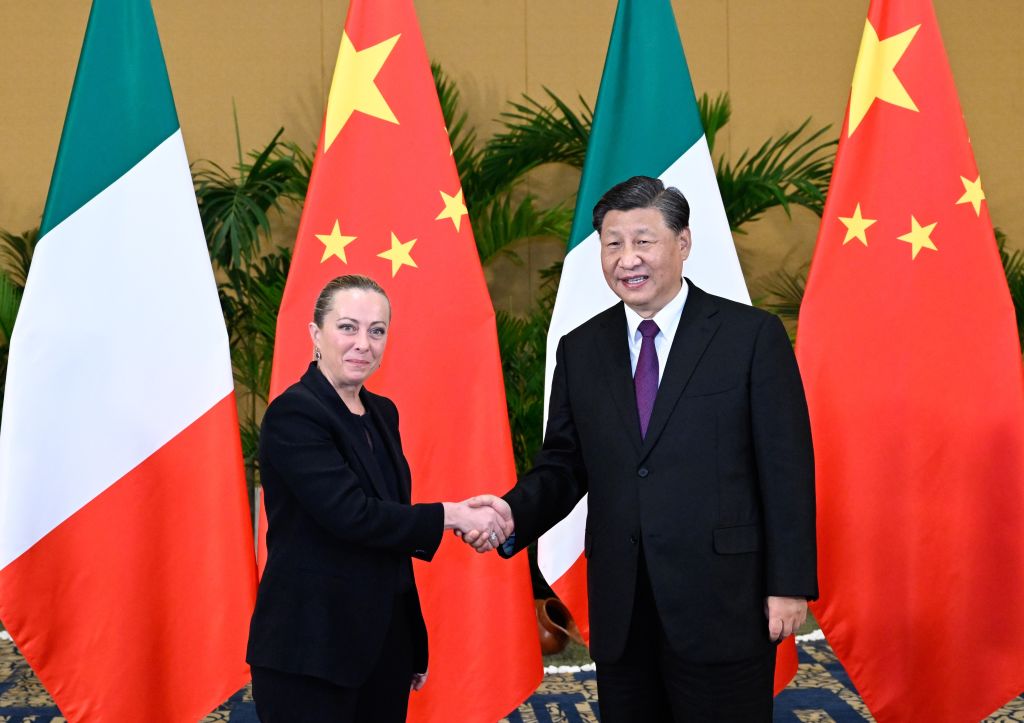

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni put her stake in the ground early on, deriding a previous administration’s decision to join the BRI as a “big mistake” before taking office last October. A visit to Washington, D.C., last month and a one-on-one meeting with President Joe Biden appeared to strengthen this conviction, despite the White House’s early misgivings about Meloni’s far-right government. A joint statement from Meloni and Biden after the trip affirmed their countries’ commitment to “free, open, prosperous, inclusive, and secure Indo-Pacific,” adding that they would collaborate to deal with the “opportunities and challenges” posed by China.

For Chinese President Xi Jinping, the timing of Italy’s about-face couldn’t be worse. This year marks the 10th anniversary of the BRI, a milestone Xi plans to celebrate with a multi-day summit in Hong Kong next month. European countries, including Italy, are reportedly skipping out on the festivities.

In addition to viewing the BRI as an extension of Chinese soft power, Western observers have scrutinized the initiative as predatory, arguing that it saddles developing countries with unsustainable debt. Italy is the wealthiest nation to sign on to date, joining the BRI in 2019 after a period of economic downturn in the hopes of getting Italian goods to Chinese markets. But that never paid dividends for Rome. Italian exports to China grew incrementally from 14.5 billion euros in 2019 to 18.5 billion euros in 2022. Chinese exports to Italy, meanwhile, shot up from 33.5 billion euros to 50.9 billion euros in the same period.

A similar story is unfolding across Europe, and it goes beyond the BRI. The EU’s trade deficit with China surpassed 395 billion euros in 2022—double what it was just two years ago. For many in Brussels, the ballooning figures underscore the need to break the bloc’s economic reliance on Chinese imports.

EU trade commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis this week vowed to reverse the imbalance, which he attributed to China’s reluctance to give the bloc market access. “The China-EU trading relationship is very unbalanced. China is running a huge trade surplus,” he told Financial Times. “And the level of openness from the Chinese side is not the same as the level of openness from the EU side.”

Chinese officials, meanwhile, said Europe’s restrictions on the sales of “high-tech products” were at fault. “China has never deliberately sought trade surplus,” a foreign ministry spokeswoman said Tuesday. “If the EU truly wants to address this issue, it needs to lift export controls against China, rather than putting the blame on China.” The spokeswoman didn’t specify which EU export controls were driving the deficit, but the U.S. has in the past encouraged its European partners to limit Chinese access to critical technologies.

Beijing itself recently moved to restrict the export of germanium and gallium—metals used for semiconductors, electric vehicles, fiber optics, and other high-tech products. Amid this technological tit-for-tat, European officials have stressed the need to “de-risk” their trade relationship with China by shoring up and diversifying their supply chains.

But Europe’s pivot from China is political as it is economic, particularly as Beijing throws its weight behind Russia. Meloni in particular has been outspoken in her support for besieged Ukraine and views Beijing’s close ties with the Kremlin as a liability in its relationship with Italy.

Rome’s decision to withdraw from the BRI now has a “political overtone, which is to signal to China that it can’t support Russia in its invasion of Ukraine and threat to European security, and at the same time assume that its relationship with NATO allies and EU countries is going to remain the same,” David Sacks, a fellow for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, tells The Dispatch. “It is, in a sense, imposing a cost—even if this is just a reputational cost—on China for those decisions.”

About two-thirds of European Union members are currently signed on to the initiative, but don’t expect them to follow Italy’s lead in formally pulling out. “Countries are generally cautious about formally withdrawing from BRI because of a fear of what China will do to retaliate. And so I think that the path of least resistance is basically to formally stay in BRI, but not really tout your membership in the initiative or really push for new projects,” Sacks adds. “I don’t think that we’re going to see necessarily a domino effect of every European country that’s in BRI formally withdrawing.”

Still, Europe as a whole has taken a tougher tack with Beijing since Russia’s invasion. Ahead of a visit to China this spring, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen castigated Beijing’s ambition to effect “a systemic change of the international order with China at its center,” she has said. “One where individual rights are subordinated to national security. Where security and economy take prominence over political and civil rights.”

The European Union’s new approach to Beijing is a welcome development for American policymakers, who have long advocated for a clear-eyed view of Xi and his Chinese Communist Party.

“European countries still talk about cooperation as an element of their China policies, but that’s no longer the predominant emphasis. The shift has been to emphasizing rivalry and competition,” says Sacks. “While the European position is not fully in line with the U.S. position, I think that there’s increasing alignment on the challenge that China represents.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.